Failed Manhood on the Streets of Urban Japan: The Meanings of Self-Reliance for Homeless Men

Tom Gill

The two questions Japanese people most often ask about the homeless people they see around them are “Why are there any homeless people here in Japan?” and “Why are they nearly all men?” Answering those two simple questions will, I believe, lead us in fruitful directions for understanding both homelessness and masculinity in contemporary Japan.

The first question is not quite as naive as it might sound. After all, article twenty-five of Japan’s constitution clearly promises that “All people shall have the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living,” and the 1952 Livelihood Protection Law is there to see that the promise is kept. For many years the government refused to address the issue of homelessness on grounds that it was already covered by existing welfare provisions. The second question, usually based on the evidence of visual observation, may be slightly more naive than it sounds, since homeless women may have good reason for staying away from areas where there are many homeless men and thus are not necessarily immediately noticeable. Nonetheless, there is abundant quantitative data suggesting that at least 95% of homeless people, in the narrowly-defined sense of people not living in housing or shelter, are men.1 Men are I believe more likely than women to become homeless in all industrialized countries,2 but nowhere is the imbalance quite as striking as in Japan.

Thus the two questions I raised are closely related. Livelihood protection (seikatsu hogo) is designed to pay the rent on a small apartment and provide enough money to cover basic living expenses. People living on the streets, parks and riverbanks may be assumed to be not getting livelihood protection, which means in turn that they have not applied for it, or they have applied and been turned down, or they have been approved but then lost their eligibility. And since most of the people concerned are men, our inquiry leads us toward a consideration of Japanese men’s relationship with the welfare system.

A woman at risk of homelessness is far more likely than a man to be helped by the Japanese state. For a start, there are two other welfare systems designed almost exclusively for women: support for single-parent families ( frequently referred to as boshi katei, literally meaning mother-and-child households) and support for victims of domestic violence. One reason why so few women show up in homeless shelters is because many women who lose their home are housed in facilities designated for one of these other two welfare categories. But perhaps more significantly, even today the core family unit tends to be conceptualized in Japan as mother and children. When families break up, children will usually stay with their mother and that group will get more help from the state than the detached father. The mostly male officials running the livelihood protection system tend to show a paternalistic sympathy for distressed women, especially if they have children, whereas distressed men are more likely to be viewed as irresponsible drunkards, gamblers, etc. In child-custody disputes courts usually side with the mother, and fathers often have a hard time even visiting their children since visitation rights are not included in Japanese divorce law. Endemic sexism punishes members of either sex who attempt to step outside their approved roles: in this case men wanting to nurture their children. But those same courts are also notoriously weak at enforcing alimony and child-support payments,3 which in a different way tends to drive the man apart from his family: if he makes a clean break, it may be relatively easy to stay in hiding and avoid payments. Thus material interests, legal systems, and cultural expectations conspire to separate the man from his wife and family.

My belief is that the phenomenon of homeless men in Japan results from a gendered conception of personal autonomy that finds expression in two ways: firstly, in a deeply sexist welfare ideology that penalizes men for failing to maintain economic self-reliance, while largely keeping women and children off the streets because they are not expected to be self-reliant in the first place; and secondly, in a concern with self-reliance on the part of homeless men grounded in conceptions of manliness (otokorashisa).

The key term, ‘self-reliance,’ is the usual translation of the Japanese jiritsu. It crops up frequently in welfare circles, notably in the name of the new law enacted in 2002 to support homeless people, the Homeless Self-Reliance Support Law (Hōmuresu Jiritsu Shien-hō), and significantly echoed by the Disabled People Self-Reliance Support Law (Shōgaisha Jiritsu Shien-hō) enacted in 2005. It is one of a cluster of frequently-used expressions – jiritsusei (self-reliance, independence), jishusei (autonomy), shutaisei (agency, autonomy, or for Koschman, ‘subjectivity’4) – clustered around the theme of the individual’s control over his own fate. Self-reliance, I contend, is a gendered term in a patriarchal society that has not expected women to be self-reliant, nor encouraged them to be so. All officials in local and central government would presumably like to see homeless men become self-reliant, but they define the idea in different ways and have different ideas as to how to achieve it.

Here is a micro-level example of the regional variation in thinking on self-reliance. Tokyo’s Ōta-ryō shelter gives each man a packet of twenty Mild Seven cigarettes a day. Staff explained to me that most of the men using the shelter were smokers, and if they were not given cigarettes, they would have to go around the streets looking for dog-ends, which would damage their self-respect. Mild Seven cost 300 yen a pack and are one of the principal mainstream brands smoked by salarymen. The Hamakaze shelter in Yokohama gives each man ten Wakaba cigarettes a day.

|

Hamakaze municipal homeless shelter, Kotobuki-chō, Yokohama |

This is a rougher brand than Mild Seven, costing 190 yen a pack and smoked by those who cannot afford better. The need to supply the men’s smoking habit is still recognized, but they are not to be spoiled by being given a whole pack of mainstream cigarettes such as people in regular employment smoke. The Nishinari Self-Reliance Support Center in Osaka gives its residents no cigarettes; instead the residents are made to work for 15 minutes every day, on cleaning and tidying the premises. Their wage for this labor is 300 yen – which they can feed into the cigarette vending machine in the lobby to buy a pack of twenty of their preferred brand. Here too, the importance of maintaining the men’s self-respect is emphasized, though this time the threat is seen as coming from getting something for nothing, rather than from having to search for dog-ends.

|

Nishinari Self-Reliance Support Center, Osaka |

Thus in these early days of homeless policy in Japan it is possible to observe officials and social workers wrestling with the concept of personal self-reliance at the same time that they struggle to find effective ways of getting homeless people off the streets. In the course of these efforts, a new ideological category appears to be emerging. It used to be that people either could achieve independence (in which case they got a job and lived on their own income), or could not, in which case they would depend on another person, typically a husband or father, or, in the absence of such a person, they would depend on the state by getting livelihood protection. Now the new emphasis on “self reliance support” creates an intermediate category: people who are not independent, but with some support, could become independent. This may be read as an attempt to avoid creating a culture of welfare dependence by returning homeless people to productive life; or, more cynically, as a way of postponing a solution to the problem while reducing costs by marooning homeless people in a series of cut-price temporary shelters while denying them livelihood protection. Both those mind-sets are at work in the system, I believe. However, with self-reliance emerging as such an important trope in debate on homelessness and welfare, I propose in this paper to focus on the men themselves, using the lifestyles and discourses of some homeless Japanese men known to me as a way to illuminate the meaning of ‘self-reliance’ for homeless Japanese men.

In his study of poor black men in the Chicago projects, Alford Young notes the tendency of scholars to neglect the views and beliefs of the subjects themselves, and to ascribe to them “the traditional, often troublingly simplistic pictures of these men as either extremely passive or overly aggressive respondents to the external forces of urban poverty.”5 Researchers of marginal men in Japan face similar temptations to portray them as passive victims or as active resisters, though two recent major works in English largely succeed in steering between these two stereotypes. Hideo Aoki views underclass men as patching together improvised lives in the face of extremely difficult external circumstances.6 That matches my own impression, though perhaps the socio-economic environment is somewhat less brutal than Aoki suggests. Rather than simply condemning and abandoning underclass men, I would argue, the Japanese state has shown a kind of repressive tolerance, sometimes rewarding men who show effort to conform to mainstream norms. Miki Hasegawa focuses more tightly on resistance to the authorities by homeless men in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, emphasizing the complex relations between the men themselves and the activists who attempt to support their resistance, sometimes to the point of taking it over.7 Aoki and Hasegawa both provide valuable insights into the relationship between homeless men and the Japanese state. However, neither of these works takes a very close look at individual men, and this is what I will attempt to do here, introducing five homeless Japanese men, each unique, but each dealing with the challenge of conceptualizing self-reliance while living on the margins of Japanese society today. I could not possibly claim that these five men are ‘representative’ of the many thousands of homeless men in Japan today; I will merely state that men like this are among that population. Each is resident in a different Japanese city, and each is in a different living situation, so at least in a small way I have attempted to reflect the variety of lives being lived by marginal Japanese men today.

Ogawa-san: Can collector

In the city of Kawasaki, between Tokyo and Yokohama, the price of scrap aluminum climbed to 185 yen per kilo in summer 2007, driven by soaring demand from China’s fast-growth economy, strong local demand, and price competition among scrap-metal dealers. Several residents of the Aiseiryō homeless shelter were making a modest income from collecting cans, and one of them, Ogawa-san, showed me the ropes. We set out at 6 a.m. for the district of Furuichiba, where local householders were due to throw out their metal waste that morning.

By 6:30, there were a dozen homeless men on bicycles criss-crossing the zone, competing with us. Ogawa said the competition was hard but fair. No-one would attempt to grab somebody else’s cans off the sidewalk, for instance, or to muscle in on a garbage spot already being foraged by another man.

|

A good haul of cans |

On this morning we found several large caches of beer cans, and we soon amassed thirteen kilos of cans, plus two kilos of pots and pans. We sold the lot to a local scrap metal dealer for 2,800 yen. On a day like this Ogawa can make more than the minimum hourly wage (720 yen in Kawasaki), albeit for only a few hours. We took the money straight round the corner to the FamilyMart convenience store and used some of it to buy booze, which we slowly consumed lying under a tree in nearby Fujimi Park.

As Ogawa told me, the aluminum-based lifestyle is a fragile thing: one never knows when the price of aluminum might collapse. (Indeed, scrap metal prices plummeted about 50% in the months following the global economic crisis of fall 2008, with a severe impact on homeless lifestyles.) On the other hand, he pointed out, high prices attract more people wanting a share of the rich pickings. Many homeless people these days are competing for cans with local residents associations and scrap dealers, as well as each other. Moreover, some local authorities have put locks on the collecting places and declared it an offense for anyone other than municipal garbage-collectors to remove the contents. What was once viewed as trash is now widely seen as a valuable resource. Kawasaki’s mighty neighbor, Yokohama, has passed such an ordinance.8

|

Nakajima Kinzoku, a Kawasaki scrap metal dealer, had the air of a gold-rush town in 2007 |

Obviously, then, can-collecting is an improvised survival aid, not an unorthodox career choice. Still, the cycling recyclers of Kawasaki tell us quite a lot about homeless men in Japan. Can-collecting as practiced here is an economic activity with an unpredictable outcome and plenty of room for personal strategy and tactics. As such it is likely to appeal to the kind of man who likes to gamble. Consider Ogawa-san. He is a strong, stocky man of average height, with weather-tanned skin and terrible teeth. He was sixty-seven when I met him, having been born in 1940, on the border between Hiroshima and Shimane prefectures in western Japan. For over twenty years he had a cushy job, working for a public corporation that supervised the Yokohama docks. He says he earned a good salary for doing little work. He was married to his second wife, the first having been a teenage adventure many years before, but never had children. The second marriage was not a happy one. He says his wife was a depressive woman whom he saved from suicide. But he admits he treated her badly. “I never took my wife on holiday; I hardly even took her out for a meal. Any spare cash I had was used for gambling.”

Ogawa’s main weaknesses were bicycle racing and slots. He reckoned nearly everyone in his shelter had a gambling problem. Maybe Kawasaki has more compulsive gamblers than the average city, with bicycle and horse-racing tracks right in the center of town. But the slots and pachinko are worse, he says, because racing happens only at certain times of day, but there is always an open pachinko / pachisuro9 place – and the money disappears faster. He can’t blame his wife for leaving him after he lost his job. It was his fault. She is back in Kobe now, with her folks. He hasn’t phoned her for some years.

I asked Ogawa why he did something so self-destructive. He offered three reasons: boring married life, too much free time at work, and easy access to gambling facilities. But the first of these he described as the biggest factor.

Being over sixty-five, Ogawa is old enough to be approved for livelihood protection, yet he has not applied. This, he says, is not out of pride or principle, but for the pragmatic reason that he is waiting for the statute of limitations to expire on his unpaid debts. If he applied for welfare, he would need to get a certificate of residence, which would expose his whereabouts to his creditors. If approved for welfare, he would have to hand over most of the monthly income to loan sharks. For now it is better to make a little cash collecting cans, keeping a low profile, and staying away from the bureaucracy. He understands that under Japanese credit law his debts will be cancelled after five years of non-collection, and he has about a year to go. The homeless shelter he was staying in was scheduled for closure the following year, and he was thinking of applying for welfare shortly after that.

I believe that many homeless men in Japan are not on welfare for similarly pragmatic reasons. They are waiting, either because of some legal issue like Ogawa’s, or because they are not yet over the age of sixty and expect to be turned away by welfare officials. These pragmatic types are often overlooked in the debate on welfare, which tends to polarize towards the rival ideological models of the man too proud to apply and the man turned away for no good reason by prejudiced officials.

The phenomenon of can-collecting by homeless men presents a tricky challenge to the Japanese authorities. On the face of it, it should be welcomed: rather than begging, or passively waiting for welfare or charity, these men are getting on their bikes in search of gainful activity. Yet can-collecting is viewed as problematic. First, it is widely assumed that most of the money raised goes straight into alcohol or gambling, enabling homeless men with addictions to maintain them without feeling much pressure to reform their lifestyles. Secondly, it resembles day labor in being an opportunistic, unscheduled economic activity that does not require a regular working week. For both these reasons, can-collecting is viewed by many welfare professionals as a barrier to leaving homelessness and unemployment, rather than a possible first step on the ladder out, and hence the activity is specifically prohibited in many homeless facilities.

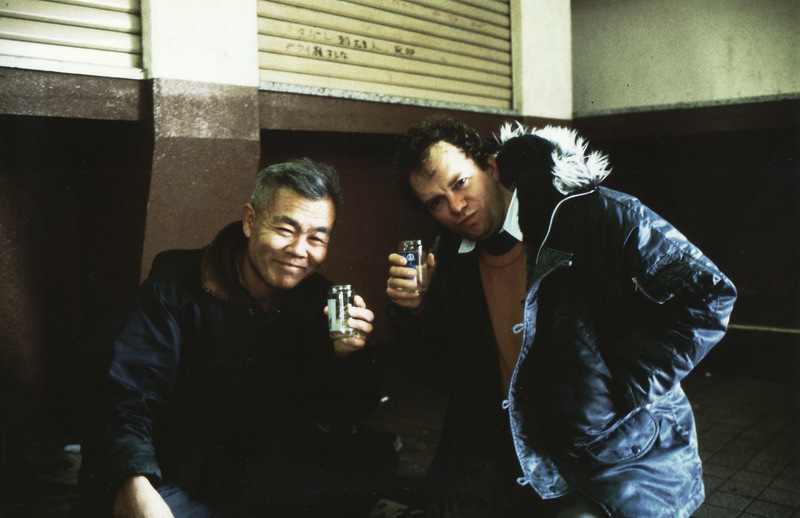

|

Ogawa-san with the author |

Hotoke: Park Life Resistance

In Nagoya there is a locally famous homeless man who humorously calls himself ‘Hotoke’ – a complex term meaning variously ‘Buddha’, or a spirit, usually of a deceased person, that has achieved enlightenment, or an unusually kind person. As a matter of principle, Hotoke tells no-one his real name or other personal data. He always says that he is zero years old and was born on planet Earth.

Hotoke embodies the spirit of self-reliance. I first met him in 2002, the year the Homeless Self-Reliance Support Law was passed. At the time there were close to a thousand homeless men living in three great parks in central Nagoya – Wakamiya Ōdori Park, Shirakawa Park and Hisaya Park. Hotoke was living in a large shack in Shirakawa Park with a tent-like awning attached to it, with a lot of furniture, bric-a-brac, and books. The city government was building a homeless shelter in Wakamiya Ōdori Park and officials were going round the park dwellings, trying to persuade their owners to use the shelter when it opened. (Men who did not have shacks or tent dwellings were not allowed to use the shelter, a policy reflecting the shelter’s objective of clearing the parks of homeless dwellings.)

|

Hotoke on a nocturnal visit to Shirakawa Park |

Hotoke stoutly refused to leave. Two years later he was one of only eight men still living in Shirakawa Park when the city authorities and police came to forcibly expel the hold-outs. Dragged from his dwelling, which was then dismantled and removed, Hotoke still refused to leave the park. While the other men went into the shelter or hospital, Hotoke took to living under a tree (just like the original Buddha, Siddhattha Gautama).

His one-man show of resistance lasted six months, until June 3, 2005. That day two city officials interrupted Hotoke while he was cooking. In a moment of irritation, he flicked some miso soup at them. Hotoke was arrested for allegedly assaulting and injuring the two city officials in the course of their duties. At his trial in the Nagoya District Court, true to form, Hotoke refused to give his real name, age, or date of birth. He was consequently denied bail and had to spend the seventeen months of the trial in detention. Finally he was convicted and sentenced to a fine of 300,000 yen, converted (at the standard rate of 5,000 yen per day) to two months’ imprisonment, meaning that Hotoke was free to go as he had already served far more than that. Hotoke appealed the decision to the Nagoya high court. In September 2007 he won a small victory when the judge upheld the assault charge but turned down the second charge of causing actual bodily injury and reduced the fine from 300,000 to 200,000 yen. Hearings in both court cases were held before courtrooms packed with Hotoke’s friends and supporters.

Hotoke is an interesting case for our theme of self-reliance: stubborn as a mule, he has fought a one-man crusade against the authorities long after most men would have given up. But his self-reliance is not total: he has drawn on alternative sources of support, such as the local day-laborer union and gifts from supporters. And when he has fallen ill, Hotoke has on occasion used hospitals where his bills were covered by the medical arm of the livelihood protection program. His powerful expression of individual resistance is made possible partly by a pragmatic willingness to accept certain forms of assistance from individuals, and even occasionally from the city of Nagoya, which he nonetheless refers to as ‘Bullyville’ (Jakusha-ijime-shi).

In January 2003 the official count for street homeless people in Nagoya was 1,788. By January 2007 that had been reduced to 741, and by January 2011, to 446. This has largely been accomplished by clearing homeless people out of the three big parks. While shelter has been offered to those who will leave their homemade dwellings, those who do not accept the shelter on offer may be subject to forcible eviction, like Hotoke and his friends, and elaborate systems of roped crash-barriers have been used to close off growing areas of parkland to prevent homeless people setting up new dwellings (pics 7 and 8). By summer of 2007, Shirakawa Park and Hisaya Ōdori Park had been completely cleared of homeless men, and a couple of hundred were still living in Wakamiya Park, hemmed in by the municipal barriers and evidently under siege.

|

Anti-homeless barriers in Wakamiya Park Homeless shacks on the Nishinomiya bank of the Muko River |

The city strategy had met with some quite well-planned resistance. In 2007 Hotoke was living in an ingeniously designed hut on wheels, which he could move short distances if told to do so by police. He explained that it had been built by Makiguchi-san, a former day laborer from Osaka who had built some 20 of these wheeled huts and lent or rented them to homeless people. Makiguchi had also negotiated a deal with the city government to allow homeless people in Wakamiya Park to draw water from public hydrants in the park. Makiguchi’s ingenuity and stubbornness had turned him into a third force in the relations between the authorities and homeless people in Nagoya – making him another intriguing image of self-reliance.

|

Hotoke’s house on wheels Hotoke in October 2011 |

I found time to revisit Wakamiya Park on October 31, 2011. Four years on, Hotoke was still living in his house on wheels, still successfully defying the authorities. The number of homeless men living in Walamiya Park was sharply reduced – perhaps thirty or forty remained.

Tsujimoto-san: Walden on the Muko River

Several homeless men have cheerfully described themselves and their friends as ‘lazy’ in conversation with me. One of those was Tsujimoto-san, who lives near Osaka, in a stout, well-constructed shack on the Muko River, on the border between Nishinomiya and Amagasaki. Born in Saitama in 1944, Tsujimoto was sixty-three when I got to know him and had lived on the Nishinomiya side of the river for a decade after many years of wandering around Japan. Thin and slight of build, he has glasses and a much lined face that frequently creases further into a smile or laughter. He was shy and preferred not to be photographed.

The riverbank lifestyle is one that appeals to homeless men in search of peace and quiet. Compared with the park communities, riverside dwellings are far less likely to be removed and their residents are less likely to be harassed by police or city officials. As well as being locations with fewer passers-by than city parks, riverbanks have a complex administrative structure, divided between various branches of city, prefectural, and national governments, which tends to result in administrative paralysis and benign neglect of homeless settlements. The stretch of the Muko River where Tsujimoto lives is close to two provincial cities and a nearby railway station gives easy access to Osaka, so it is suburban rather than rural and combines convenience with relative tranquility. On the other hand, the same relative remoteness and administrative neglect that makes riverbanks peaceful locations can be dangerous when fights break out or gangs of youths come to harass homeless men. Moreover, riverbanks are at risk of flooding, as was dramatically demonstrated in August 2007, when 28 homeless men were rescued by helicopter from the Tama River between Tokyo and Kawasaki after a typhoon caused the river to burst its banks.

Tsujimoto tours neighborhoods on the day of the month when ‘large-scale general refuse’ (sodai gomi) is being put out and has had some success in finding jewelry, fine china, and other valuables. Even so, he estimates his average monthly income at just 15,000 to 20,000 yen. He has a sheaf of technical qualifications, permitting him to work as an electrician and operator of various kinds of construction machinery. He also claims to have a second-class diploma in abacus (soraban), and certificates for flower-arranging and tea ceremony. His neat and tidy hut does somewhat recall a tea ceremony house, and when conversing with visitors, he kneels in front of it in the upright seiza style, which he says he finds comfortable. He says he could easily get employment – labor recruiters have approached him several times. But like Melville’s Bartleby, he prefers not to. “I have no appetite for work. I’m tired of worrying about what other people think, tired of boss-underling relationships. Since coming here, I’ve felt at ease.”

Tsujimoto’s lifestyle seems comfortable: he has time for hobbies such as reading historical fiction and playing shōgi with friends or video games on his Gameboy. He has a small TV that he runs off a car battery, regularly recharged for him by a friend. He has oil lamps for lighting and camping gas for cooking. About ten men live in the immediate vicinity. He says they get on very well, though he never shares food with them. To him, that is a symbolic indicator of excessively intimate friendship. Like many homeless men, including homeless author Ōyama Shiro (2000, 2005), he says he deliberately avoids intimate friendships for fear of incurring obligations.10 Occasionally he will make fishing trips, travelling vast distances on his bicycle; he says the fish in the Muko River are not worth catching. He mentioned that there were three male-female couples and one gay male couple among the 150 to 200 dwellings on the banks of the Muko River. He once knew of a single woman, but she was long gone.

Like Ogawa, Tsujimoto had a working career that was far from the lumpenproletariat. The youngest son among seven siblings, he graduated from senior high school and started out working for a firm that maintained and repaired printing presses. He traces his wanderlust to the frequent business trips that this specialized profession entailed. He quit after five years and drifted from job to job thereafter. His electrician’s qualifications enabled him to earn good money – indeed, sometimes he could make 10,000 yen without lifting a finger, just by allowing some maintenance company to put his name on the safety certificates for electricity sub-stations, “which never break down anyway.” Thus a period of earning easy money is another point he shares with Ogawa.

But whereas Ogawa said he was pragmatically playing out time before applying for livelihood protection, Tsujimoto insisted that he had never applied for it, and would never do so in future. When I asked him why not, he said “I don’t want to live anymore” and added that he had attempted suicide three times. He did not want or need to have his livelihood protected. When a local volunteer encouraged him to apply for welfare when he got older and weaker, he replied that he would sooner “enter” (throw himself into) the river (kawa ni hairu) than enter an apartment (apāto ni hairu). Either that or he’d hang himself from the tree we were sitting under. He said he was tired of life and was living only by inertia. Yet this was said with a good-humored laugh, and I could not guess how serious his talk of suicide might be. Tsujimoto also said he had no interest in using the self-reliance support centers in nearby Osaka. He did not trust any institution set up by politicians, whom he viewed with contempt.

It is tempting to think of Tsujimoto as a Japanese Thoreau, retreating to a semi-rural location, maintaining a self-reliant lifestyle and casting a cold eye on modern society. That said, Tsujimoto is situated firmly within the cash economy, preferring to use income from his scavenging activities to buy food from a supermarket rather than farming. Indeed, I found few cases of homeless men growing vegetables or keeping chickens, though admittedly in many locations legal obstacles would have made it difficult to do so. One reason I chose to explore the Muko River was because I had read an account of homeless keeping chickens on the river bank, but Tsujimoto said the local authorities had put a stop to that some time before.

Yoshida-san: Railing at Society

The biggest riverbank settlement in Nagoya is along the Shōnai River. It was there that I found Yoshida-san, living under the Shin-Taiko Bridge in a small shack by a footpath. On the other side of the footpath, twenty yards away, were four more shacks surrounded by an immense quantity of stinking trash. Two at least were clearly uninhabited and the trash had literally invaded them, warping the walls and spewing out from cracks.

Yoshida-san looked to be about 40. He was a stocky man, running to fat, with unkempt beard and wavy black hair, wearing black shorts and sweat-stained gray tee-shirt. Initially suspicious of my presence, he became increasingly talkative and our conversation lasted several hours. He told me that the mountain of stinking garbage on the other side of the path was the legacy of a homeless man who had been driven out with threats of violence by Yoshida and a couple of his friends. Since then, the local authorities had several times said they were going to clear away the garbage but they had yet to do so. To Yoshida, this was absolutely typical of the rank incompetence and cynical lying of government in Japan.

|

Shōnai River Yoshida’s dwelling place |

Where Tsujimoto’s view from the riverbank was one of world-weary ennui, Yoshida’s was darker and more cynical. “Japan is finished,” he several times remarked. He had various conspiracy theories – all the state-run gambling games were fixed, for instance, and elections likewise were decided in advance. After each rant, he would raise his eyebrows, shrug his shoulders and say “right?” (sō deshō?) with the bored air of one who knew the score. It was all so obvious – Japan was a society run by the rich, for the rich, totally corrupt and deeply unfair. It was like an army, in which lower ranks had no power over higher ranks. He knew from experience that employers would mercilessly exploit their workers. Government policies to help homeless people were a mere excuse to keep people off the welfare rolls. The state pension, just 70,000 yen a month, was tantamount to abandoning the elderly to death – and now the government had just admitted to losing millions of pension records.11 For Yoshida, mainstream religion was a money-making scam with no interest in helping the weak and poor – he said the fact that most of the food handouts for homeless people were done by Japan’s tiny Christian minority should make the Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines feel thoroughly ashamed of themselves.

For Yoshida, abundant evidence of the corruption and incompetence of government and other large organizations meant that only an idiot would place any trust in the system. “In this country,” he asserted, “there isn’t a single person you can rely on. All you can do is live for yourself.” To him, this meant taking advantage of whatever resources he could find around him. As well as scavenging for cans etc., which he said brought in a cash income of 20-30,000 yen a month, this also meant queuing for handouts and foraging for food. The local McDonald’s had been an excellent source for some time – the manager had put out leftovers for homeless people every night. Now, however, due to a new city ordinance defining leftover food as industrial waste, the manager was obliged to pay good money for a company to take the leftovers away and destroy them – much to Yoshida’s exasperation.

This gradual criminalization of food-foraging may be placed alongside the gradual expulsion of dwellings from parks, the tentative criminalization of can-collecting, and the crackdown before that on re-selling magazines picked out of trains and stations, as part of a consistent pattern whereby the state delegitimizes self-reliant activities performed by homeless people. Masculine pride, in Japan and many other parts of the world, is tied to being able to look after oneself. Yet it seems that, despite the government rhetoric of ‘self-reliance,’ when a man is down on his luck, almost any attempt to look after himself without resorting to the welfare system will, one way or another, run afoul of the law. Note, incidentally, that for Yoshida, food-foraging and queuing for hand-outs were activities constructed totally differently from applying for welfare. At first glance all these activities may seem like an admission that one cannot support oneself. But to Yoshida, collecting food thrown out by restaurants and shops was something requiring effort and local knowledge, and not entailing dependence on the state. The handouts, likewise, came from fellow private citizens rather than the hated state. Meanwhile, he contended that the mountains of food destroyed each day under government regulations amounted to yet another national disgrace.

Yoshida said he had been homeless for five years, ever since he had been laid off. He used to work for one of the many auto-part makers supplying Toyota Motor in nearby Toyoda city. What with low wages, a lively social life and a keen interest in pachinko, he had no savings to tide him over. He had wound up spending the night in a local park, was attacked by schoolboys, and was rescued by a kindly older man who, despite being slightly mentally handicapped, showed him how to survive homelessness. He owed his life to this man.

|

Yoshida’s neighboring shack |

Eventually the old man fell ill. He was hospitalized and told to apply for livelihood protection on discharge. But it was just before Golden Week (the series of public holiday at the start of May), and the hospital discharged him when the welfare offices were closed. Although he could barely walk, he was told to make his way to the emergency homeless shelter and stay there until the holiday ended and he could be placed in a welfare apartment. Yoshida helped him hobble to the shelter and left him there. When he returned to visit three days later, the man was gone. He’d apparently left the shelter barefoot, for he’d left his shoes behind. Yoshida has never seen him since. He blames the welfare authorities. When a person is going to be put on the rolls to receive livelihood protection, the welfare office conducts extensive background checks to make sure the person really has no financial resources and nobody who might provide for them. The latter search starts with parents, siblings and children, and may extend to distant relatives or even unrelated friends. The shame of being the subject of such an investigation is a major factor deterring people from applying for welfare – especially men, since, as mentioned above, self-reliance is a key part of their masculine self-image. Yoshida thinks this is what made his friend run away.

In many parts of Japan local schoolboys will violently harass homeless men for their amusement. Another informant, Hirayama-san, who lived in a large shack in Osaka Castle Park, said that if homeless men did not fight back, the schoolboys would lose interest and give up harassing them. Yoshida, however, took the opposite view. When local boys threw stones at homeless men, it was vital to resist them. He always did. The kids were all cowards at heart. He would give their bicycles a good kicking, or frog-march them to the local police box and demand to see their parents. He said that once he slapped one of them in front of his parents, to teach the whole family a lesson. He added that every summer, just before the school holidays began, he would ask the police to issue circulars to local schools ordering pupils not to attack homeless people.

One source of Yoshida’s bitterness is a sense that he has not been given a fair chance in society. One of six siblings in a poor family, he says he left school after completing junior high school because his parents could not afford to send him to senior high. He regrets that and would like to somehow catch up on his education and escape from homelessness. He struck me as a man whose cynicism and belligerence covered up an all too evident insecurity. Self reliance and self defense were obsessions for him, but he also looked to mutual assistance among homeless men as a way of keeping safe in a dangerous world. He had a good friend, a former postman, who lived in one of the shacks near the mountain of garbage. Yoshida also said that he would advise and assist newly-homeless men who arrived at the riverbank, sometimes encouraging them to use the same support facilities that he himself spurned. I had just visited one of the self-reliance centers and showed him some of their published materials. He was surprised at the range of services available and I thought I saw his cynicism waver as I bade him farewell.

|

Some of Yoshida’s possessions |

For Yoshida, informal bonds of mutual assistance between homeless men were a viable alternative to dependence on the government-run welfare system. His powerful attachment to the old man who showed him the ropes was an expression of that impulse. Where Tsujimoto sought security in solitary independence, Yoshida sought it in friendship and cooperation with his peers, a set of pure autonomous relations he contrasted with the cynicism and corruption of non-homeless society. Here we start to sense why his kind of conception of masculinity is problematic to the state: he valorizes free association between men in groups that cannot be co-opted into larger social units – so unlike the stereotypical corporate warrior whose fight for his company is so often compared to that of a soldier fighting for the nation. Yoshida’s vision of masculine self-reliance was specifically opposed to the state and hence liable to be stamped down upon.

Nishikawa-san: The Broader View

My final case study is of a man who got off the streets by successfully applying for welfare. For many years now Nishikawa-san12 has been living alone in one or another of the cheap lodging houses of Kotobuki-chō, Yokohama. He used to support himself by day laboring, but has been living on livelihood protection for some years. Classical American definitions of homelessness13 would include Nishikawa, since he is largely cut off from family and society, but he draws a clear distinction between himself and men who live in the street. He sees himself as having escaped from homelessness, and he had no hesitation in applying for livelihood protection when he felt the time was ripe. For him, welfare is just another of the resources available in post-modern society. Although he sacrificed a degree of autonomy when he signed on for welfare and sometimes expresses gratitude to the Japanese nation for supporting him, it did not harm his pride much. This is because Nishikawa does not believe anyone is really autonomous or self-reliant. He argues that some people may appear autonomous, but in fact their lives are intertwined with broader society and their thoughts conditioned by the surrounding culture and media.

|

Nishikawa with the author in 1994 |

Born in 1940, Nishikawa is one of many Japanese men whose lives were decisively influenced by Japan’s defeat in World War II, although he was only five years old when it happened. He says he still remembers his confusion on seeing the tall American soldiers arriving in his native Kumamoto at the start of the Occupation. As a small child, he did not fully grasp the difference between these giant warriors and the Nazi storm troops he had seen on cinema newsreels. One moment these supermen had been conquering Europe; now here they were taking charge of Japan.

After the war, Nishikawa went to high school, where many of the teachers had fought in the war and would brag about their exploits and wounds. He recalls the deep sense of disgust he felt about that – how could they brag when they had lost the war? After graduating, he joined the Ground Self-Defense Force and was stationed first at Sasebo in Kyushu, and later at the Makomanai base near Sapporo. Nishikawa enjoyed the all-male society of the military and was inclined to romanticize it as a ‘society of knights.’ He said: “it’s because there are no women that such an ideal society is possible, at least for a fleeting moment. If women come in it gets dirtied immediately.” He stressed that he was not talking about homosexuality, but a pure society of comrades – a common trope in pre-war Japanese thinking. Yet this deeply sexist celebration of all-male society was offset by a wry awareness that the war was over and so these soldiers would likely never see action. As he said, it was more like playing at soldiers, or “being in the boy scouts or a school club”. For him, it was deeply refreshing to enjoy the military life safe in the knowledge that any real fighting would probably be done by the Americans.

Built by the Americans during the occupation and recently vacated by a U.S. unit, Makomanai Base placed the military masculinity of the conqueror in another register. The facilities were bigger and better than at Japanese bases and were in American log cabin style. Nishikawa especially admired the exceptionally large library – it seemed to speak to a superiority of intellect to match that of bodily strength and military technology already demonstrated.

By his own account, Nishikawa has never had sex without paying for it. In this he resembles homeless day laborer Ōyama Shirō (a pseudonym) whose memoir of life on the margins was translated into English as A Man with No Talents.14 Intensely shy with women, he has never been able to contemplate relations without being totally drunk. When he was in the GSDF, his fellow officers sometimes took him to the Sapporo pleasure district of Susukino. A brief session with a prostitute would cost 1,000 yen, in an era when a soldier’s pay was about 6,000 yen a month. On the rare occasions when the drunken Nishikawa managed to achieve penetration, he recalls being rewarded with a sudden sharp pain in his penis, which would somehow get pinched in the inter-uterine contraceptive device favored by the Susukino women. He called this a ‘plastic curtain,’ obstructing intimacy between men and women. For him it symbolized the fundamental impossibility of true love or communication between the sexes.

|

Nishikawa’s sketch of the ‘plastic curtain’ |

To Nishikawa, prostitution was not a sign of men’s power over women. On the contrary, the fact that men had to pay through the nose and then experience intense pain led him to the rueful conclusion that “in a matrilineal society like Japan, men can never win out over women.” Contrary to the mainstream academic consensus, he often argued that Japan was a matrilineal society and even read violence and cruelty by Japanese men as expressions of their frustrations at being unable to dominate women. His opinions echoed Bourdieu’s observation, that “manliness… is an eminently relational notion, constructed in front of and for other men and against femininity, in a kind of fear of the female, firstly in oneself.”15

Like many Nihonjinron scholars, Nishikawa also sees deep significance in diet, over-simplifying Japan and the US as fish- and meat-eating cultures. He attributes Japan’s defeat in the war to the fact that a woman-dominated fish-eating nation was taking on the patrilineal and meat-eating Americans. Like so many Japanese men of his generation, he recalls seeing American soldiers out on dates with Japanese girls: “The men seemed so big, and the women so small. We’re not meat-eaters so it can’t be helped.”

Spells of homelessness after he quit the GSDF brought a new twist to Nishikawa’s ‘gaijin complex.’ In the West, he mentioned, homeless men would usually have some kind of skill – they’d do conjuring tricks, or play the violin, or do juggling like Peter Frankl (an eccentric Hungarian mathematician, known for doing juggling shows in the streets of Tokyo – hardly a representative homeless man). Homeless Japanese men, by contrast, had no special skills and would just carry on walking the streets until they keeled over and died.

As the postwar years rolled by, Nishikawa read widely and was especially influenced by Colin Wilson’s The Outsider. Wilson’s 1956 study of modern culture heroes, fictional and real, sees alienation from mainstream society as a defining feature of those who have deep insight into the human condition. From his own outsider’s perspective, Nishikawa started to question his infatuation with American muscular virility, turning to what he saw as its dark side. He developed an obsessive interest in violent crime in the US. He could name half-a-dozen American mass murderers, complete with the dates, locations, and circumstances of their crimes.

Nishikawa had a deep sense of shame regarding his failure to be a credit to his family – a sense made all the more acute because he is an oldest son, out of three brothers and one sister. On learning that one of his brothers had died in a traffic accident, he reflected: “He was only a year younger than me, but I bullied him constantly. I thought I was some kind of Emperor just because I happened to be the oldest son. I was an A-class war criminal.16 Now that he was dead, I felt personally responsible as oldest son for failing to protect him.” In such ways are personal and public issues entwined in Nishikawa’s mind. His discourse is a lament for lost masculinity, in which his own life as an alcoholic day laborer, narrowly saved from death on the streets by the Japanese welfare system, becomes a microcosm of Japan’s defeat in war and of an inadequacy in Japanese men that he sees as persisting despite the great economic revival of the postwar years. That lingering regret for failed manhood is a theme I often come across among homeless men, though never expressed so clearly as by Nishikawa.

That said, going on welfare does not necessarily mean abandoning all traces of self-reliance. Many Kotobuki men drink away their welfare money in the first few days of the month and are then penniless again. Nishikawa is not like that. He husbands his resources carefully, calculating each day’s expenditure so that even on the last day of the month he can still purchase the four or five glasses of cheap saké that he requires to keep himself going. In the last couple of years he has even made several trips back to his native Kyushu, to see his sister and look for old school friends, riding slow local trains, outrageously fare dodging and feigning drunken unconsciousness when accosted by authority. His feelings of shame are focused elsewhere, on deeper matters. Self-reliance for him is an unattainable metaphysical ideal; reliance on an employer or a welfare agency, an incidental detail.

|

Nishikawa enjoying a drink |

Conclusion: Homelessness, Self-Reliance, Masculinity

Many of the men I have been studying are difficult to fit into English-language homeless terminology, with its bipartite distinction between ‘street homeless’ (or in British parlance, ‘rough sleepers’) and ‘sheltered homeless.’ Japanese shack dwellers are not exactly on the street, or in a shelter as usually conceived. Their dwellings are homemade; they are mostly quite well-built. Though most are small, some are large enough to bear comparison with a small apartment. I have observed some that have legal postal addresses with mail delivered to them. Some have furniture; some have guard dogs or pet cats. Many have gas from camping stoves, some have water supplies from nearby fire hydrants, drinking fountains etc., and a few have electricity from car batteries. At least one case has been documented of a homeless dwelling with a solar panel supplying electricity.17 And the great majority of these dwellings are clustered into smaller or larger settlements which arguably represent a kind of alternative community.

There is considerable interest in the design of Japanese homeless dwellings, including several art/photography exhibitions and at least three published collections of photos, sketches, and text – Sogi Kanta’s Asakusa Style (2003), Sakaguchi Kyōhei’s Zero-yen House18 (2004), and Nagashima Yukitoshi’s Cardboard House (2005). These books testify to the resourcefulness and skill of the men who build, maintain, decorate, and live in them. As well as admiring the skill of the design, one is also struck by the air of domesticity, the homeliness, of these dwellings. When large numbers of them are gathered together in village-like communities, one begins to wonder whether ‘homeless’ accurately describes these men.

Living without women and with very little cash obliges shack-dwellers to acquire skills long since lost to most Japanese men and considered the preserve of women. In a society where many men can barely peel an apple, they must cook for themselves. They also have to build, maintain, furnish, and repair their own living space, unlike most men, who will pay professionals to do these things for them. So although they have very little by way of income or possessions, and may on occasion join lines of people waiting for food hand-outs, in some ways they actually seem more self-reliant than most mainstream men.

As with can-collecting, so with park-dwelling: Japanese cities have gradually turned the screw on this lifestyle, which is seen – not without justification in some cases – as obstructing the use of parks by non-homeless people. The typical approach has been to lure shack-dwellers into temporary prefabricated shelters, threatening any who refuse to go with forcible expulsion, as in Hotoke’s case, and fencing off vacated areas of parks to prevent newcomers or returnees from settling there (see pics 7 and 8 above, pic. 20 below). By such methods have the authorities gradually whittled down the park populations. The elaborate homemade dwellings celebrated by Sogi, Sakaguchi and Nagashima are becoming steadily harder to find.

|

Scaffolding designed to prevent shack construction on the Kizu River, Osaka |

The irony is that once these rather self-reliant men have been put through the shelter system, they will likely be either clients of the state (living on welfare), or in a more desperate homeless condition, expelled from their park communities and reduced to living in cardboard boxes. Hence ‘self-reliance support’ may actually reduce men’s degree of self-reliance. The figures released by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare on 6 April 2007, showing a 26.6% reduction in non-sheltered homeless people to 18,564 from 25,296 four years earlier, and further reductions reported to take the population to 15,759 in January 2009, and all the way down to 10,890 in January 2011, largely reflect the gradual war of attrition on the park settlements. Some of those evicted men may well still be homeless, but away from the more noticeable concentrations. Many others will be on welfare; the number of people receiving livelihood protection reached 2.06 million in the fall of 2011, a postwar record. A greater willingness to admit that people require welfare is probably a much bigger factor in the reduction of street homeless numbers than the government’s legislation and policy measures to combat homelessness. At the same time the steady decline in secure employment, the corresponding increase in the numbers of freeters, dispatch personnel and other insecure forms of labor, and an unemployment rate hovering around 4.5%, as opposed to 1-2% during the economic miracle years, means that the declining numbers of homeless people does reflect underlying socioeconomic realities, but merely a greater willingness to resort to welfare.

As mainstream society slowly tightens the noose on homeless settlements, repressively throwing them onto the street or tolerantly placing them in welfare hostels and cheap apartments, how do homeless men conceptualize their place in society? Connell and Messerschmidt observe that ‘“masculinity” represents not a certain type of man but, rather, a way that men position themselves through discursive practices.’19 How do homeless Japanese men position themselves?

Though my informants show a tremendous variety of personality, outlook and lifestyle, they have certain things in common. For a start they do not beg – and this is something true of most homeless Japanese in my experience. In contrast, most of them do not seem to hesitate to accept food handouts (takidashi) from volunteers, NPOs etc. What is shameful is to ask for help, not to accept what is offered. This may also explain why some men who will not apply for livelihood protection will nonetheless stand in line for hours, day after day, to receive minimal emergency assistance such as Yokohama’s 714-yen food vouchers (pan-ken). Some of these men have been turned down for livelihood protection – others insist that they do not want full-scale welfare, just a little help to get by. Yet others prefer to apply for the vouchers because they are not subjected to the obtrusive checks on their economic status and attempts to contact family that inevitably accompany a welfare application (see the case of Yoshida’s elderly friend above). So accepting assistance entails a kind of hierarchy of shame. Begging is seen as the most abject abandonment of masculinity, and very few homeless Japanese men will do it. To beg is to openly admit one’s inferiority vis-à-vis the man (or worse still, woman) from whom you beg. It is a loss of manhood in the sense of adulthood as well as masculinity – only children beg to get something for nothing. It leaves no room for psychological maneuver. Accepting food handouts from activists or charity workers is less humiliating because at least one is not forcing one’s need on other people. Those who hand out the food assuage shame by addressing the homeless men (who are typically older than themselves) as senpai (senior), creating an image of inter-generational cooperation rather than one-sided charity. Standing in line for food tickets is also a humiliating business, but in a sense the tiring wait at the ward office makes the activity somewhat akin to work done to get pay. Applying for livelihood protection feels to some like an admission of failed manhood comparable to begging, though others see livelihood protection as comparable to the pension they never got from their decades of insecure labor. Informal economy activities such as can recycling fit very well with notions of masculine self-reliance, making it all the more galling when the state delegitimizes such work.

In short, each of the survival strategies available to homeless men in Japan carries different implications for masculinity, usually as constructed relative to the state, or broader society. That has been the main sense in which I have used the term in this paper. When masculinity is constructed relative to women, a bleaker picture emerges. None of the men discussed here has been able to sustain married life; none of them can expect to be looked after by a wife, daughter or daughter-in-law in old age; none of them has a girlfriend or can even afford to go with prostitutes; and the best they can hope for in terms of female companionship is a friendly smile from a matronly waitress at a cheap bar.20 Viewed in this light, these men look much more like cases of failed manhood. Yet the way they talk positions them not relative to women but relative to the state or mainstream society – perhaps because they sense they are on firmer ground in the latter debate.

Along with this range of survival strategies comes a range of ‘discursive practices’ open to homeless men as they seek to position themselves within Japanese society. My case studies give some indication of the options available. They may adopt a pragmatic approach that ekes out a minimal level of survival until the welfare system kicks in (Ogawa); a radical refusal to compromise with the repressive-tolerant authorities (Hotoke); a hermit-like detachment from mainstream society (Tsujimoto); outright denunciation of mainstream society and an emphasis on camaraderie among those living on its margins (Yoshida); or a metaphysical view of human life that makes the differences between mainstream and margin appear trivial (Nishikawa). What these varying strategies have in common is that they soften the blow to the ideal of masculine self-reliance that comes from not being able to support oneself economically in a mainstream lifestyle.

In their various ways, these men are trying to come to terms with their failure to match conventional views of manhood. As some of them point out, the stereotypical salaryman is far from self-reliant himself. He relies on his company, his boss, his wife, etc. His autonomy is also limited. Despite the language it employs, the Homeless Self-Reliance Support Law is really an exhortation to homeless men to trade in one mode of limited autonomy for another – to become self-reliant in a narrowly-defined, socially sanctioned way. As the slow but steady criminalization of homeless lifeways proceeds, I anticipate that the increasingly beleaguered settlements of huts and tents may take on the character of last redoubts. As their inhabitants are gradually expelled, they will be pushed further from mainstream society, or brought into the welfare system, their masculinity further undermined by the need finally to abandon the brave image of the self-reliant man.

This is a revised, expanded, and illustrated version of a chapter that appears in Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall, eds., Recreating Japanese Men (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

Tom Gill is a professor of social anthropology in the Faculty of International Studies at Meiji Gakuin University. He has written extensively in Japanese and English on the lives of underclass men in urban Japan, including Men of Uncertainty: The Social Organization of Day Laborers in Contemporary Japan (SUNY Press). His current research centers on comparative studies of the British and American underclass.

Recommended citation: Tom Gill, ‘Failed Manhood on the Streets of Urban Japan: The Meanings of Self-Reliance for Homeless Men,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 10, Issue 1 No 2, January 2, 2012.

Articles on related subjects:

• Yoshio Sugimoto, Class and Work in Cultural Capitalism: Japanese Trends

• Stephanie Assmann and Sebastian Maslow, Dispatched and Displaced: Rethinking Employment and Welfare Protection in Japan

• David H. Slater, The Making of Japan’s New Working Class: “Freeters” and the Progression From Middle School to the Labor Market

• Toru Shinoda, Which Side Are You On?: Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics http://japanfocus.org/-Toru-SHINODA/3113

• Kawazoe Makoto and Yuasa Makoto, Action Against Poverty: Japan’s Working Poor Under Attack

• Fujiwara Chisa, Single Mothers and Welfare Restructuring in Japan: Gender and Class Dimensions of Income and Employment

• Glenda S. Roberts, Labor Migration to Japan: Comparative Perspectives on Demography and the Sense of Crisis

References

Aoki, Hideo. 2006. Japan’s Underclass. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Caplow, Theodor, Howard M. Bahr and David Sternberg, 1968. ‘Homelessness.’ in David Sills, ed., International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. New York: Macmillan, 1968, 494-99.

Connell, R.W. and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. ‘Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.’ Gender and Society 19: 829-859.

Curtin, Sean. 2002. ‘Japanese Child Support Payments in 2002.’

Link.

Gill, Tom. 2001. Men of Uncertainty: The Social Organization of Day Laborers in Contemporary Japan. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Hasegawa, Miki. 2006. We Are Not Garbage! The Homeless Movement in Tokyo, 1994-2002. London: Routledge.

Hayashi, Mahito. 2007. ‘Seisei suru Chi’iki no Kyōkai: Naibuka Shita ‘Hōmuresu Mondai’ to Seidōka no Rōkaritii’ (Reproducing Regional Borders: The Internalized ‘Homeless Problem’ and the Locality of Systematization). Soshiorojii 52(1) 53-69.

Koschmann, J. Victor. 1996. Revolution and Subjectivity in Postwar Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Murayama, Satomi. 2004. ‘Homeless Women in Japan.’ Kyōto Shakaigaku Nenpo 157-168.

Nagashima, Yukitoshi. 2005. Danbōru Hausu (Cardboard House). Tokyo: Poplar.

Ōyama, Shirō. 2000. San’ya Gakeppuchi Nikki (A Diary of Life on the Brink in San’ya). Tokyo: TBS Britannica.

———-. 2005. A Man with No Talents: Memoirs of a Tokyo Day Labourer. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Patari, Juho. 2008. The ‘Homeless Etiquette’: Social Interaction and Behavior Among the Homeless Living in Taito Ward, Tokyo. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag.

Sakaguchi, Kyōhei. 2004. Zero-en Hausu (Zero-yen House). Tokyo: Little More.

———-. 2008. Zero-en Hausu Zero-en Seikatsu (Zero-yen House, Zero-yen Life). Tokyo: Daiwa Shobō.

Sogi, Kanta. 2003. Asakusa Stairu (Asakusa Style). Tokyo: Bungei Shunju.

Young, Alford A., Jr. 2003. Minds of Marginalized Black Men: Making Sense of Mobility, Opportunity, and Future Life Chances. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Notes

1 For example, a government survey conducted in January 2009 and published on March 9 2009, counted 495 homeless women in a total homeless population of 15,759, equivalent to 3.1% (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/seikatsuhogo/ homeless09/index.html). Murayama (2004), writing specifically about homeless women in Japan, also gives a figure of about 3%.

2 In the United States and United Kingdom, for example, surveys have generally found homeless populations to be roughly 70% male.

3 Curtin 2002.

4 Koschman 1996.

5 Young 2003, p. 6.

6 Aoki 2006.

7 Hasegawa 2006.

8 Odawara was the first city in Kanagawa prefecture to ban can-collecting, in 2004. In the next couple of years, Yokohama, Zama, Kamakura, Chigasaki, Fujisawa and Hiratsuka followed suit. Hayashi 2007, p. 20.

9 A place where you can play pachinko or slot machines.

10 Many homeless men will avoid using their surname and will also refrain from asking someone else their surname or other personal details. Patari (2008) quotes some informants in Ueno Park as describing this as ‘homeless etiquette.’

11 In February 2007 the Social Insurance Agency admitted that it had lost track of some 50 million pension records when it changed its computer system in 1997. In November 2008 someone carried out knife attacks on two of the bureaucrats involved in the mess-up, killing one of them and his wife.

12 An intellectual day laborer who features in my book, Men of Uncertainty. Gill 2001, pp. 168-170.

13 “Homelessness is a condition of detachment from society characterized by the absence or attenuation of the affiliative bonds that link settled persons to a network of interconnected social structures.” Caplow et al, 1968:494

14 “I have never slept with a woman who was not a prostitute. I am, in short, a man with no talents who is incapable of relating to women or coping with work.” Ōyama 2005, p. 128.

15 Bourdieu 2001, p. 53.

16 A reference to the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal of 1946-8, in which class A (‘crimes against peace’) was one of three classes of crime considered, usually thought of as the most serious category.

17 Sogi 2003, p. 19; Sakaguchi 2004, pp. 182-3.

18 Some of Sakaguchi’s photos of homeless dwellings may be viewed at his home page.

He published a sequel in 2008, Zero Yen House Zero Yen Life, focusing on a single brilliant shack architect encountered on the bank of the Sumida River in Tokyo.

19 Connell and Messerschmidt 2005, p. 841.

20 Whether the men discussed here actually desired female companionship is a moot point. Hotoke and Tsujimoto spurned conventional married life and valorized their solitude; Ogawa had tried marriage and failed; Yoshida just did not have the wherewithal to get a girlfriend; and Nishikawa was too shy to even contemplate the possibility. I do not think any of these men were gay; whether some of them really had no need of women, or whether such talk was a psychological defense mechanism, I really cannot say.