Gilded Outside, Shoddy Within:The Human Rights Watch report on Chinese copper mining in Zambia

Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong

A November 2011 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report on labor abuses in mining firms in Zambia parented by state-owned enterprise (SOE) China Non-ferrous Metal Mining Co. (CNMC) has been a media sensation.1

|

A Zambian does construction work at China Luanshya Mine as a Chinese manager looks on. China Luanshya Mine is one of four copper mining companies in Zambia operated by the Chinese parastatal China Non-Ferrous Metal Mining Company. From the HRW report. Thomas Lekfeldt/Moment/Redux |

CNMC subsidiaries operate two copper mines and two copper processing plants in Zambia:Non-Ferrous Company Africa (NFCA), CNMC-Luanshya Copper Mines (CLM), Chambishi Copper Smelter (CCS), and Sino Metals Leach Zambia (Sino Metals). In 2010 CNMC’s two mines accounted for 4.5% of the copper concentrate produced by foreign companies in Zambia and 4.2% of Zambia’s total. Myriad news outlets and blogs have reported HRW’s conclusions about CNMC: that the Chinese firms are ‘bad employers’ compared to the five Western-based major foreign investors in Zambia’s copper mining industry; that they have the worst record on the safety of workers, pay, hours and union rights. Despite HRW’s focus on one industry in one country, the report provokes inferences that accord with the larger, highly-skewed Western discourse of ‘China-in-Africa.’2 Indeed, HRW asserts (p.1) that its report ‘begin[s] to paint a picture of China’s broader role in Africa.’

HRW investigations are widely assumed to be empirically accurate, methodologically sophisticated and politically neutral. We challenge these assumptions with respect to the HRW report on CNMC in Zambia, which draws empirically problematic conclusions and uses a dubious methodology.

Throughout the world, and notably throughout Africa and Asia, mining is dangerous and often low paid work with long working hours, particularly for irregular workers. These are serious problems to be addressed by workers and governments in all countries and internationally. The issue reviewed here, however, is the assessment of Chinese mines in comparison with other foreign-owned mines in Zambia.

Readers of the HRW report may be overwhelmed by its basis in interviews with miners. We do not wholly dismiss concrete observations made by interviewees about rights deficiencies they experienced, such as having to work in unsafe conditions. CNMC firms employ some 6,000 workers and Zambia’s total mining work force is almost ten times as large.3 Those interviewed by HRW included some 95 who had worked only at a CNMC firm and 48 who had worked elsewhere. Those who worked only in a CNMC firm or only in a non-CNMC firm cannot, however, reliably infer from their own experiences that CNMC operations are less safe than elsewhere.

Miners who formerly worked at other mines and now work at CNMC mines may not necessarily make sound comparisons either, as observations of safety practices experienced by a worker at another mine, such as the UK/Indian-owned Konkola Copper Mine (KCM) in 2008 and then at NFCA in 2011, do not tell us about safety practices at NFCA in 2008 or KCM in 2011.More importantly, the HRW report does not tell readers whether those interviewees who worked at a non-CNMC firm before moving to a CNMC one were contract or permanent workers when they worked at the non-CNMC firm. This is significant because contract workers generally have much worse experiences with safety as well as lower pay and fewer benefits. Many, if not all, HRW interviewees who worked first at a non-CNMC firm and then at a CNMC company had been permanent employees when they worked at the non-CNMC mine. After being laid off in 2008-2009, they were hired by a CNMC firm. Thus, they had experienced only the better safety conditions of permanent employees while at the non-CNMC firm and not the worse safety conditions that contract workers at these firms experience. In making judgments about comparative safety conditions, they therefore could not represent the experiences of non-CNMC workers as a whole. Despite HRW’s claims then, its miner interviewees could not speak authoritatively about how safety at CNMC firms compare to safety at other firms.

HRW relies on interviews as the method of investigation. Interviews can be very useful for investigating specific incidents of abuse, but exclusive reliance on interviews is insufficient to draw general conclusions about the extent of abuse, still less does it enable understanding of comparative implications. That research objective can only be achieved by supplementing interviews with survey data from a range of mining companies.

Inferences of ‘worst practices’ drawn by interviewees about Chinese-owned firms are also highly suspect. A climate of intense anti-Chinese prejudice was whipped up from 2005-2011, especially in mining areas, by then-opposition leader and now Zambian president Michael Sata and his Patriotic Front, in order to advance their election campaigns.4 Studies show that racialized discourse shapes attitudes and distorts evaluations on a wide range of issues.5

|

President Michael Sata has been very critical of Chinese-run mines |

The HRW report itself contains internal contradictions. It makes generalizations that cannot be supported by the specifics that it provides. For example, the report generalizes (p. 24) that “Chinese copper mining companies offer pay base salaries around one-fourth of their competitors’ for the same work.” There is no qualification that this applies only to CNMC processing plants, where just 20% of CNMC firm employees work. The report’s annex on wages differentiates however between pay in CNMC’s processing plants and its underground mines. Contradiction also exists between the report and generalizations about the report made by the report’s author himself (not to speak of the media), as we show below, concerning the issue of the number of hours required of workers. In both instances, the generalization makes out the CNMC firms to be worse than they are. This creates a methodological and political problem: while the report is specific regarding some details, at the same time it generalizes the worst to characterize CNMC practices, thus encouraging even more general inferences about Chinese practices in Africa. In this article we examine conditions at CNMC and throughout the mining industry with an eye both to gauging levels of abuse and assessing worst case charges.

HRW’s Simplistic Safety Comparisons

Days after HRW issued its CNMC study, the president of the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ) Oswell Munyenyembe responded to it by saying that ‘his union cannot entirely blame the Chinese companies because other mining houses are equally culprits.’ He added: ‘We cannot wholesomely condemn the Chinese-owned mining houses. Remember when we had the global crisis no worker was retrenched at any Chinese mine [unlike at other mines]. Yes, they have their own problems like mistreating workers and not following labor laws, but other mining houses are also culprits in this area. It is not only the Chinese mining companies.’6

The MUZ president thus disputed HRW’s central argument: that CNMC, among the foreign investors dominating Zambian mining, is almost uniquely culpable of abusing workers’ rights.

The single most important measure of whether a mining company is deficient in safety compared to other firms is whether (other things being equal) that firm accounts for a large disproportion of fatalities. Mining firms in Zambia cannot avoid reporting deaths. Injuries may go unreported, but serious ones correlate with fatalities, most as a result of rock falls.7 Given the small number of fatalities that occur in Zambian mines, comparisons of fatality rates between different firms are not significant. However, a comparison between fatalities at CNMC firms and the cumulative total for all foreign-owned copper firms for 2001-2011 is a reliable way to determine whether CNMC’s safety record is extraordinarily bad.

Statistics provided by the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ) on fatalities in all foreign-owned copper mines and for CNMC-owned operations indicate that CNMC is unexceptional.

|

Mining fatalities in Zambia and any other country of course represent a serious problem. The figures are not, however, especially high by world standards; Zambia is not among the 60 most dangerous countries for miners listed by the International Federation of Chemical, Energy, Mine and General Workers’ Unions. The ICEM noted, for example, that “The year 2010 . . . saw the gruesome deaths of 29 miners at the Pike River coal mine in New Zealand, caused perhaps by ventilation fans located inside mine shafts instead of outside. Twenty-nine miners also died in the US on 5 April 2010 at the Upper Big Branch mine in the state of West Virginia, a tragedy that saw mine owner Massey Energy and its CEO shift blame – unbelievably – to the stringent safeguards enshrined in the US Mine Safety and Health Act.”9

In 2010-2011, there are about 55,000 workers in Zambia’s foreign-owned mines, of whom 10.5 percent, or 5850, work for CNMC’s two mining companies. CNMC-firm fatalities in Zambia – 11.5 percent of the country’s total from 2001 to late 2011 – are not a very disproportionate number, which contradicts the claim that CNMC mines’ safety conditions are markedly worse than its industry peers.

HRW asserts that the supposedly worst conditions at CNMC firms ‘stem largely from the attitude of Chinese owned and run companies in Zambia, which have tended to treat safety and health measures as trivial’ and which ‘appear to be exporting abuses along with investment.’ The death toll in non-ferrous mining in China is much higher (about 83 miners per 100,000 miners in 2009)10 than that in Zambia (about 30 per 100,000 for 2008-2011). As CNMC-owned firms do not have an especially high fatality rate by Zambian standards, the assertion that CNMC exports safety abuses does not mesh with its record in Zambia.

Explaining CNMC’s safety outcomes only in terms of attitudes is in any case simplistic. The relative number of fatalities is not determined solely by the level of safety consciousness of mining firms. It is also the product of operational configurations of mines. Underground mines typically have more casualties than open cast (open pit) mines. The deeper underground mining goes, the greater the likelihood of rock falls and casualties.11 CNMC firms have two mines in Zambia: CNMC’s Non-Ferrous Company Africa (NFCA) has Chambishi, which at over a thousand meters is a deep underground mine. CNMC Luanshya (CLM), at least 580 meters deep, is also underground. (An open pit mine being developed in Luanshya is scheduled to begin operations in 2012.) Underground mining is not only more dangerous, but also more costly, so it negatively impacts wages as well as safety. While the difference in the dangerousness of underground, compared to open-pit mining in Zambia cannot be determined due to difficulties in disaggregating the available data, based on data on all U.S. mines fatalities in recent years, the fatality rate of underground mining is nearly 3 times that of surface (open-pit) mining.12

|

Zambian workers 580 meters below the ground in Luanshya Copper Mine run by the Chinese company China Non-Ferrous Metal Company. |

No other large Zambian copper mining firm has only underground mines; some have open cast mines and some are mixed underground/open cast operations. Konkola Copper Mine (KCM) is owned by Vedanta, the UK Indian major. KCM Nchanga open pit mine (55 percent of production), plus KCM Nchanga underground mine (45 percent) had 32 fatalities from 2001-2011, while KCM Konkola, an underground mine, had 31 fatalities. Mopani Copper Mine (MCM) is owned by the Switzerland-based mining and metals trading giant Glencore. MCM Nkana has underground and open cast mines and had 55 fatalities from 2001-2011, while MCM Mufilira, an underground mine, had 27 fatalities.13

Skill levels also affect safety and they are lower at CNMC mines than at other mines. In large measure this is because most other mines have been open continuously, thereby creating more skilled and experienced workers, while both the mines now operated by CNMC were closed for long period before the company acquired them. NFCA’s Chambishi mine was closed for thirteen years and the Luanshya mine was closed from 2000 to 2004 when it was owned by the Binani Group of India and closed again from 2008 to 2009 by its owner Switzerland-UK-based J&W/Enya.

When copper prices increase, expansion occurs and fatalities tend to rise as new workers are brought in to expand production. For 22 months, from October 2006-August 2008, NFCA had zero-fatalities, a rarity in the industry. When asked about its fluctuating record, CEO Wang Chunlai explained that, “Before, we only had one ore body to work on; now we have two [and] now we go down to more than 1,000 meters. The ceiling there gets unstable and that can create injury . . . As the scale of work enlarges, we’ve recruited more new workers, so our training may be lagging and we have to invest more in training.’14 As to CLM, the director of Zambia’s Mine Safety Department (MSD) told us that it had the industry’s best dust abatement system15and from June 2009-December 2010, CLM had only one fatality.16

Unsafe conditions of service remain an industry-wide problem, as detailed in a study by John Lungu of Copperbelt University and Alastair Fraser of Oxford University.17 There have also been firm-specific studies of Chibuluma mine under South Africa’s Metorex firm,18 KCM,19 and MCM20 that have shown substantial safety problems. In a 2011 interview with us, the MSD Chief Inspector of Mines spoke negatively of NFCA, but only of its first five years in operation (2003-2008), when he said it ‘was the worst mine in terms of safety. It didn’t want to do sufficient support work. And it didn’t have proper ventilation.’ Now, however, ‘NFCA is OK’ in terms of safety, so ‘NFCA no longer stands out.’21

No one, including CNMC, asserts there are no safety problems at its Zambia facilities and, at these and other mines, such problems require urgent attention. Taking into account fatality figures and differences in the configuration of mines however, there is no basis to claim that CNMC is the worst in terms of safety. To do so serves mainly to reinforce hoary racist stereotypes which have endured for more than a century in the West and have been spread to Africa, that Chinese are cruel and have a disregard for human life.22

Wages and Hours: The Exaggerated Gap?

CNMC still has to catch up on pay, but there is a narrowing trend. In a 2011 interview, John Lungu compared miners’ basic salaries at the two CNMC Zambia mines with the country’s largest foreign mining firms.

‘MCM and KCM are the best payers among the mine owners. But the Chinese have responded to criticisms. The lowest wage in Chambishi went up from 400,000 Kwacha to K1.5 million and there’ve been later increments . . . Chinese companies have not caught up completely with the Western companies in terms of incomes in the mines, but they’re not lagging behind too much. There’s been substantial improvement.’23

KCM and MCM each have workforces around three times the CNMC mines’ total workforce and produced, in 2010, 5-13 times the amount of copper concentrate (138,000 tons for KCM and 98,000 tons for MCM versus 22,000 tons for NFCA and 10,000 tons for CLM).24 But apart from the global tendency of large, more productive enterprises to pay better wages than smaller, less productive ones,25 there are Zambia-specific reasons why there is still a wage gap between CNMC and larger Western-based mining firms. One is the costs of rehabilitating Chambishi, which was closed for 13 years and flooded before CNMC acquired it, and refurbishing the antiquated Luanshya mine, which had been neglected and then abandoned by previous owners.26 There are also differences in the copper content of mining concessions that affect wage levels. A section engineer at Chambishi Mine told us in 2008 that, ‘With 1.8 percent copper content, the former [owner] didn’t think it was worth their while to mine it. 1.8 percent in Zambia is considered a tail [leftovers] mine. They don’t think it was worth their effort if it’s lower than 3 percent. Other mines have 4 or 5 percent.’27

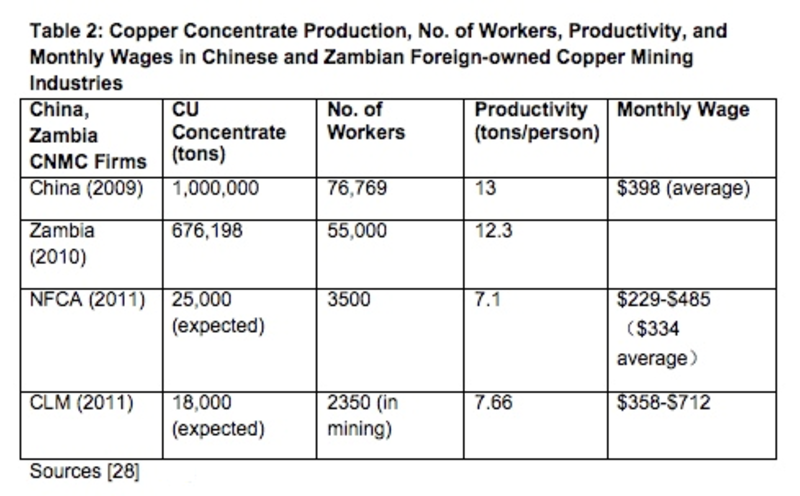

Deep underground operations and lower copper content make CNMC production more labor intensive, with lower productivity. NFCA and CLM together produced 4.7 percent of the Zambian foreign-owned copper industry’s concentrate in 2010, but had 10.5 percent of its workforce. NFCA and CLM’s productivity is thus much lower than industry averages in both Zambia and China. In the table below, the total number of workers in Zambia includes permanent and non-permanent workers employed by foreign-owned mines and their contractors.

|

We asked CEO Wang Chunlai about NFCA’s reputation for low wages. He responded that, ‘Wage levels have to do with the scale [size] and age of the enterprise. In terms of scale, we’re ranked number five and in terms of cost of labor, number five or six [as] salary increases are a cumulative annual percentage . . . NFCA is labor intensive. This can be compared in terms of tons per workers.’

There are stark differences in productivity measured that way: Canadian-owned Kansanshi produced 232,000 tons of copper concentrate in 2010 with about 3,500 workers, while NFCA produced 22,000 tons with the same number.29 Wang noted that CLM provides higher pay than NFCA because it is an older enterprise and was taken over; thus it has workers who have accumulated many years of service and have higher salaries, but starting pay at CLM is about the same as for NFCA.30

|

Kansanshi mine |

Other reasons for wage differentials emerged in our interviews. The National Union Mineworkers and Allied Workers (NUMAW) chairman at Chambishi Mine told us in 2008 that, ‘The government is responsible for the slow pay rise. It issues a benchmark every year and dictates the percentage of increase, for example 15 percent. It announced that the inflation rate in 2007 was 9.8 percent. The government is actually afraid that much of an increase in wages will destabilise the single-digit inflation. The management relies on the government benchmark to negotiate pay raises with workers’.31

HRW claims (p. 24) that ‘Chinese copper mining companies often pay base salaries around one-fourth of their competitors’ base salary for the same work.’ CNMC Company officials have said NFCA’s overall average basic pay is about half that at KCM32 while at CLM it is about 80% of KCM’s level, the industry’s highest.33 CNMC’s statements, which cover mines where 80% of CNMC Zambia employees work may be accurate, however, because workforces at KCM, MCM and other mines include many low-paid contract workers, while NFCA and CLM aver that almost all their workers are permanent employees.34 Specifically, half the 16,560 employees at MCM in November 2011 were contract workers.35 Of the 19,000 workers at KCM in mid-2011, 12,000 were permanent and 7,000 were contract workers.36

Zambia’s Deputy Commissioner of Labor has stated that contract workers may get as little as one-fourth the pay of permanent employees37 and indeed ‘[L]abor offices have recorded a number of reports especially in areas such as Mopani Copper Mines and Konkola Copper Mines where several sub-contracted companies have been paying below the government’s minimum wage requirements,’38 which is even less than a fourth of permanent employee salaries. For example, in late 2011 MCM miners reportedly were ‘typically paid’ three British pounds per day. That’s a surprisingly low figure, but only if one forgets that half of MCM’s workforce is contract workers.39 If contract workers’ low salaries at non-CNMC mines are taken into account, there may still be a gap, but not a huge one, between CNMC wages and those elsewhere. MUZ informed us, moreover, that CNMC intends to reach the “industry standard” in salaries in 2012.40

The HRW report author writes elsewhere that ‘Several Chinese-run copper mining companies require miners to work brutally long hours – 72-hour work weeks for some, 365 days without an off day for others . . . ‘41 This grossly over-generalizes the report’s actual finding and Western media have expectedly played up this ‘cruel Chinese’ theme. It is sweepingly inaccurate: the HRW report itself (p. 4) states only that ‘Miners in certain departments at Sino Metals [one of the smaller CNMC firms] work 72-hour weeks without sufficient overtime [pay], while those in other departments work 365 days a year . . .’ The report (p. 78) is unclear on how many workers have long hours, which affect workers in only some Sino Metals departments, not ‘several’ firms and certainly not most CNMC workers, 80 percent of whom work eight-hour regular shifts in the Luanshya and Chambishi mines.

The actual story of hours worked by Zambian miners does not at all correspond to the impression HRW conveys of Chinese work-‘til-you-drop bosses in contrast to enlightened managers at Western-based firms. In 2007, KCM miners reported they worked more than eight hours, often up to 12 hours, without overtime pay.42 In 2008, a Zambian seeking work at Chambishi said that ‘his countrymen prefer to be employed by the [Chinese-owned] NFCA rather than other foreign companies. They say they would rather work the eight hours demanded of them by the NFCA than the 12 hours which is commonplace in other companies.’43 In 2009, KCM miners worked four 12-hour days, then two days off.44

Cartoon by Gado (Godfrey Mwampembwa), one of Africa’s most influential cartoonists.

In 2010, a magazine report about Zambia’s large Lumwana mine, then owned by an Australian firm and now by Canadian mining giant Barrick Gold, profiled a permanent employee miner who stated that she and her colleagues work four 12-hour day shifts, then four 12-hour night shifts, followed by four days off.45 The miner noted that in earlier years, they worked 10-hour or even 8-hour shifts, but that hours have increased because now “in the operations and production phrase, we are facing a lot of pressure.” Zambian “bloggers” have said that miners at the large, Canadian-owned Kansanshi Mine work 12-hour shifts, but these claims need to be confirmed.46 A 2011 UK newspaper account noted MCM miners ‘toil six-and-a-half days a week in the rock underneath Mufulira,’ that is, more hours per week than do NFCA or CLM underground miners and, in effect, up to 365 days a year.47 Presumably, thousands of miners at MCM work that schedule, while the number of workers at CNMC Sino Metals who HRW said work every day, is apt to be very much smaller. In any case, all media reports about the HRW study that we have seen predictably assert that long shifts are a general practice of Chinese-owned mining firms – and Chinese-owned mining firms alone – in Zambia. At the same time, the HRW report itself tells readers that they should infer something from it about Chinese practices in Africa more generally.

The Union Question

HRW has charged that the two smaller of the four CNMC firms it investigated, Sino-Metals and Chambishi Copper Smelter (CCS), deny workers the right to join MUZ. Yet, at least one of the two unions (MUZ and NUMAW) is recognized at all four firms and 80 percent of CNMC workers can choose between them as their bargaining agent, although the two unions bargain jointly with management. NUMAW had 1,000-plus members and MUZ 400 at NFCA in August 2011; MUZ had 1,700 members and NUMAW 400 at CLM.48 The ruling Patriotic Front (PF) is popular among miners and both unions have PF supporters and critics among their leaders.

The facts thus far do not support the claim that CNMC firms are hostile to MUZ because it supports PF. The reason why MUZ is recognized by NFCA and CLM, but not by the two CNMC processing firms needs more investigation and HRW should have left it at that. In fact, all mining firms regard unions as problems to the extent they protect workers and as helpmates to the extent that they discourage strikes and protests, which both MUZ and NUMAW often do. What has most devastated union activism in Zambian mining was the drastic decline in membership due to retrenchment during the financial crisis. MUZ’s membership dropped from 26,000 before the crisis to 12,000 in August 2011.49 The non-Chinese foreign-owned mines and contractors layed off 19,000 workers, or 30% of the copper mining workforce total of 63,000, in less than one year between 2008 and 2009.50 When other firms retrenched or closed operations during the crisis, CNMC firms promised ‘three nots’ (san bu): not to reduce investment, not to cut down on production and not to lay off workers. Rather, CNMC bought the Luanshya mine, which had been shuttered by its Swiss owner at the peak of the crisis. It re-hired laid-off workers and hired hundreds more, which belies HRW’s claim that CNMC is a ‘bad employer’ compared to the five other major foreign investors in Zambian mining. The nickel-mining firm Albidon Ltd., with the Chinese SOE Jinchuan owning 51 percent of its shares, indefinitely suspended operations in November, 2011, due to a sharp decline in nickel prices and technical problems, but it continues to pay full salaries to its 2,000 employees.

Conclusion

Why does HRW focus on labor abuses at CNMC firms in Zambia? Labor abuse at CNMC firms and others in Zambia’s copper industry is deplorable. But it is not exceptional in the context of the African continent, which like many other parts of the world, experiences massive human rights violations, including grave labor rights violations. CNMC’s practices, seen in the context of the Zambia copper industry, are worse in some respects (pay), about the same in other respects (safety), and better in still other respects (job security). They also show signs of improving. There should be improvements across the board for mine workers in Zambia, who still receive a subsistence wage and live in underserviced communities, a possibility made less, rather than more likely when Chinese firms are singled out and erroneously accused of being the worst.

Conditions for millions of miners on the continent are so egregious that the African Union Commission on Human Rights and People’s Rights stated in 2010 that, ‘Mine workers in most parts of Africa work in deplorable conditions often prone to accidents.’51 At the same time, there has been no shortage of critical studies of labor practices in the CNMC mines in Zambia,52 which employ one-tenth of one percent of the country’s workforce. HRW is thus barking up the wrong tree. Its exclusive focus on CNMC firms in Zambia as the worst labor abuser serves no useful purpose. Rather, it plays into the racial hierarchy in Zambia and beyond by calling its report ‘a magnifying lens’ for Chinese labour practices in Africa (p. 13). It also reinforces erroneous notions promoted by Western media and politicians, such as Hillary Clinton and David Cameron,53 that China is a ‘neo-colonialist’ power in Africa, while Western states and NGOs are the guarantors of human rights.

HRW has issued many reports criticizing Chinese government practices. We have no general problem with critiques of the Chinese government. We do take issue with the fact that while HRW criticizes the Chinese government per se, its reports on Western entities mostly focus on specific private companies or errant government officials. That is so even though Western governments are responsible for massive human rights violations through wars and support for numerous authoritarian regimes in the world.

We were informed by the report’s author that the HRW report on CNMC in Zambia was written in response to calls by media, policy makers and human rights people who wanted to know HRW’s view about Chinese practices in Africa. HRW should have rejected the very idea of undertaking a study that singles out a Chinese firm, especially given the global context of repeated Western state and media attacks on “China” and “the Chinese.”

HRW decided that its first firm-level study of a Chinese investment in Africa would examine an SOE that has had some problematic labor practices in Zambia, but also has uniquely been the subject of long-running, inaccurate, and racialized attacks by biased Western and partisan Zambian media. Western media have portrayed CNMC activities in Zambia as exemplifying the malpractices of Chinese investors throughout Africa and it was thus easy to predict that media reports about HRW’s study would pour oil on the fire of anti-China/anti-Chinese sentiment. They have — and so much so that China’s media-savvy ambassador to Zambia was heard to comment that “in the ‘Western media’ . . . if you have not written something bad about China in a given day, then you have not done your job . . .”54

HRW approached its study of CNMC differently from other firm-level studies of copper mining in Zambia. NGOs that studied KCM did so “because of its sheer size.” Their report demonstrates that the development of Zambia copper mining has not benefited society at large, but has brought suffering and disadvantages.55 They did not focus on KCM because it is UK- or ethnic Indian-owned; nor did they distinguish KCM from other industry firms. A more recent study of MCM’s behavior, while very specific about it, fundamentally questions “the link between development and mining in general” and points out that MCM is “far from a stand-alone case.”56

|

KCM open pit mine |

In contrast, HRW makes CNMC an extraordinary case, in effect constructing a binary of CNMC vs. the rest (despite some qualifications). Ignoring structural conditions, such as mine configurations, scale of operation, labor-intensiveness of production, HRW interprets CNMC behavior by spuriously claiming that Chinese do not care about safety, are exporting their malpractices from China to Africa, etc. Further, unlike other firm-level studies, although it focuses on one company, the HRW report (p. 13) is self-described as “a useful magnifying lens into Chinese labor practices in Africa.” It thus makes a Chinese SOE, by way of example, a strikingly negative example of Chinese investment in Africa.

Martin Luther King was once confronted by claims that Jewish landlords and shopkeepers exploit African-Americans. He responded by stating that “The Jewish landlord or shopkeeper is not operating on the basis of Jewish ethics; he is operating on the basis of a marginal businessman” and that the solution “is for all people to condemn injustice wherever it exists.”57 Thus, alternatively, HRW could have undertaken a study of labor rights violations in Zambian mining. That would likely have found, as the president of MUZ observed in response to HRW’s report, that violations are common in mining generally. Instead, HRW erroneously maintains that that CNMC trivializes safety, seeks to export China-based mining practices to Zambia, and is a singularly “bad employer” of Zambian labor. That can only have the effect of bolstering longstanding anti-Chinese racism, which is based, in significant part, on notions of Chinese cruelty and disregard for human life.

Some readers may think that HRW’s report cannot be accused of racism because it does not claim that CNMC’s practices are racially or culturally rooted. If, however, CNMC, a Chinese SOE, is said to trivialize the safety of Zambian workers, while Western-based mining firms do not, what are readers to infer, other than that this is a “Chinese” practice? That is precisely what the media did infer. If a Chinese SOE is unwilling to carry out in Zambia better practices than in its home country, what are readers to infer, other than that it has a disregard for the lives of Zambians, which Western-based firms do not? That is what the media inferred, despite the practices of Western-based firms in Zambia that are worse than they are back in Canada, Australia, etc., while CNMC’s practices in Zambia are better than those of most mining firms operating in China.

There are distinctive aspects of Chinese investment in Zambian copper mining, but in the main Chinese firms operate like other foreign investors in the industry. They are da tong xiao yi (more alike than different), as Chinese say. The biggest difference between CNMC and other foreign investors is not “the worst” safety record (which doesn’t exist) or lower wages (explicable, albeit not justifiable), but a difference that redounds to the benefit of Zambian miners. It is that CNMC as an SOE is conscious of political factors. Western governments cannot ensure that their citizen firms provide secure jobs in Zambia; it would likely be illegal, under their national laws, for them to do so, regardless of what International Labor Organization standards may prescribe about job security. Yet, Chinese SOEs, despite in other respects practicing basically the same form of exploitation as others, can do just that.

In mining in Africa, there are also massive human rights violations, including by Western firms, many of which have varying degrees of home government backing, but thus far HRW has chosen to single out a Chinese SOE, along with a report on the Western-sanctioned Zimbabwean government (a December 6, 2011 HRW report about child miners in Mali, published after its report on CNMC, is on an uncontroversial topic). The HRW report in fact tells us more about the political agenda of HRW than about Chinese activities in Africa. Presenting itself as a golden effort to secure improved labor rights, it turns out to be yet another contribution to China bashing; the HRW report is, as Chinese say, jin yu qi biao, bai xu qi zhong, gilded outside, shoddy within.

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in Pambazuka News: link.

Barry Sautman teaches in Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. He is the author of All that Glitters is not Gold: Tibet as a Pseudo-State, Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies (Baltimore: University of Maryland School of Law no. 197), co-author with Yan Hairong, East Mountain Tiger, West Mountain Tiger: China, Africa, the West and “Colonialism”, Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies (Baltimore: University of Maryland School of Law), no. 186; co-author with Yan Hairong, “The ‘Right Dissident’: Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Peace Prize,” positions: east asia cultures critique, 19:2 (2011): 581-613.

Yan Hairong teaches in Hong Kong Polytechnic University. She is the author of New Masters, New Servants: Migration, Development and Women Workers in China (Duke University Press, 2008), co-editor with Daniel Vukovich, What’s Left of Asia, a special issue of positions: east asia cultures critique (2007).

Recommended citation: Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, ‘Gilded Outside, Shoddy Within:The Human Rights Watch report on Chinese copper mining in Zambia,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 52 No 1, December 26, 2011.

Articles on related topics:

• Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, Trade, Investment, Power and the China-in-Africa Discourse

• Philip Hirsch, China and the Cascading Geopolitics of Lower Mekong Dams

• Jenny Chan and Ngai Pun, Suicide as Protest for the New Generation of Chinese Migrant Workers: Foxconn, Global Capital, and the State

• Suisheng Zhao, China’s Global Search for Energy Security: cooperation and competition in the Asia-Pacific

Notes

1 HRW, ‘You’ll be Fired if you Refuse’: Labor Abuses in Zambia’s Chinese State-owned Copper Mines, Nov. 3, 2011.

2 On bias in UK media coverage of Chinese activities in Africa, see Emma Mawdsley,”’Fu Manchu versus Dr Livingstone in the Dark Continent? Representing China, Africa and the West in British Broadsheet Newspapers,” Political Geography 27:5 (2008): 509-529. We have made similar findings in a forthcoming paper that surveys two hundred articles published from 2005-2011in five leading US newspapers.

3 Ministerial Statement of Maxwell M.B. Mwale . . . on the Development of the Mining Sector in Zambia, March, 2011.

4 We detail the anti-Chinese campaigns of Sata and the racial hierarchy constructed by his deputy, the now Zambian Vice-President Guy Scott (Indians are worse than white and Chinese are worse than Indians) in our monograph in progress, Red Dragon, Red Metal: Chinese Investment in Zambia’s Copper Industry.

5 For example, on how people in the US evaluate welfare measures, see Paul Kellestedt, The Mass Media and the Dynamics of American Racial Attitudes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

6 “Chinese Firms not that Bad, says Miners’ Union,” DM, Nov. 4, 2011. See also “Minister, Union Defend Chinese Labor Conditions,” Zambia Watchdog, Nov. 5, 2011 (“Government [Deputy Minister of Labor Rayford Mbulu] says not only Chinese Mining companies have been flouting labor laws but all employers should try and ensure their workers are properly looked after”), zambianwatchdog.

7 H.B. Miller, et al., “Identifying Antecedent Conditions Responsible for the High Rate of Mining Injuries in Zambia,” International Journal of Occupational Environmental Health 12:4 (2006): 329-339.

8 MUZ, “Statistics of Mine Accidents by the Mine/Division for the Past 11 Years”; Mine Safety Dep’t, “Mining Industry Safety Record from the Year 2000 to August 19, 2011; “November 9 Power Failure Left One Miner Dead,” Zambia Watchdog, Nov. 20, 2011. There were also 46 dead in the 2005 BGRIMM dynamite plant explosion. NFCA owned a 40% interest in the plant, but did not manage it. MUZ does not count the BGRIMM fatalities as attributable to NFCA. We thus omit them from the totals for both all mining companies and NFCA.

9 ICEM, “Mine Safety and ILO Convention No. 176: a Continued Priority for the ICEM,” Apr. 24, 2011, link.

10 For fatalities in China’s non-coal mining sector, see the State Administration of Work Safety (SAWS) website, “2010 nian fei mei kuangshan shigu fenxi” [An Analysis of Non-Coal Mining Accidents in year 2010”, March 9, 2011, link. and a telephone interview with SAWS, Beijing, Nov. 16, 2011, that indicated that non-ferrous death was 27% among the total for non-coal mining for 2010. Fatalities figures for China involve only reported fatalities, but many Chinese mining fatalities are unreported, so that the gap between Chinese and Zambian fatality rates are significantly larger than reported figures reveal.

11 See S.K. Puri, “Safety Management in Indian Coal Mines,” in Pradeep Chaturvedi (ed.), Challenges of Occupational Safety and Health (New Delhi, Concept Publishing Co., 2006): 161-168 (166).

12 See table “Mining Fatalities: All U.S. Mines Accident/Injury Classes” in “Briefing Book for the Niosh Mining Program” (section 1.4 “Research Needs”)(Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005), link. The fatality ratio between surface and underground mining is calculated by us for the period of 1990-2004, using employment figures for 1992-2002.

13 MUZ, Statistics and Mine Safety Dep’t, Mining Industry.

14 Interview, Wang Chunlai, Chambishi, Aug. 15, 2011.

15 Interview, Mooya Lumamba, Kitwe, Aug. 19, 2011.

16 Interview, Gao Xiang, Vice CEO, CLM, Luanshya, Aug. 17, 2011.

17 “For Whom the Windfalls: Winners and Losers in the Privatization of Zambia’s Copper Mines”, Civil Society Trade Network of Zambia, 2008.

18 Austin Muneku, “South African Multi-Nationals in Zambia: the Case of Chibuluma Mines, Plc,” in Devan Pillay (ed.), South African MNCs’ Labor and Social Performance (African Labor Research Network, 2005): 258-285.

19 Action for Southern Africa, et al., “Undermining Development? Copper Mining in Zambia,” Oct. 2007.

20 Counter Balance, “The Mopani Copper Mine, Zambia: How European Development Money has Fed a Mining Scandal”, Dec. 2010: 16-17.

21 Interview, Mr. Kalezi, Kitwe, Aug. 16, 2011.

22 We discuss past and present notions of Chinese cruelty and disregard for human life, including in Africa, in a paper in progress “Bashing the Chinese: Contextualizing Zambia’s Collum Coal Mine Shooting.”

23 Interview, John Lungu, Kitwe, Aug. 15, 2011. In 2011 one US dollar was worth 4,800-5,000 kwacha.

24 “2010 Mineral Production (1st Half of Year)” and “2010 Mineral Production (2d Half of Year), photocopies provided by the authors by office of the Chief Mining Engineer, Lusaka, Aug. 19, 2011.

25 See David Creedy, et al., “Transforming China’s Coal Mines: a Case History of the Shuangliu Mine,” Natural Resources Forum 30:1 (2006): 15-26.

26 Interview, Mundia Sikufele, President of NUMAW, Kitwe, Aug. 27, 2008; Interview, Luo Tao, CEO of CNMC, Beijing, Oct. 18, 2011.

27 Interview, Section Engineer Xu, Chambishi, Aug. 23, 2008.

28 Shang Fushan, et al., “Sustainable Development of the Chinese Copper Market,” (Winnipeg: IISD, 2010): 16; China Data Online (2011), “Copper Ores Mining & Dressing/Basic Condition”; “China Yearly Industrial Data,” All China Data Center, sourced from National Statistics Bureau, 2010 Mineral Production table; Wang Chunlai interview; Interview, Gao Xiang, Exec.Vice Gen. Manager, CNMC International Trade, Beijing, Oct. 21, 2011.

29 2010 Mineral Production.

30 Wang Chunlai interview. Wang’s comparison of NFCA and KCM in terms of per worker copper production derives from “Zhongse Zanbiya bagong shijian”(CNMC Zambia’s strike incidents), Xin shiji, Nov. 5, 2011.

31 Interview, Mubanga Gillan, Chambishi, Aug. 27, 2008.

32 NFCA CEO Wang Chunlai and unions interviewed in “Zhongse Zanbiya bagong shijian” (The Incident of Strike at NFCA in Zambia), Xin shi ji Nov. 7, 2011,magazine

33 Interview, Gao Xiang, Beijing, Oct. 20, 2011.

34 Wang Chunlai and Gao Xiang August 2011 interviews.

35 Rob Davies, “The Other Face of Glencore Mining that Investors Never See,” Daily Mail (UK), Nov. 21, 2011.

36 Interview, Charles Mukuka, Acting MUZ President, Kitwe, Aug. 15, 2011.

37 Siti interview. Zambia’s minimum wage in 2011 was K419,000 (about US$85).

38 “Labor Ministry ‘War-Front’ Opens over Minimum Wages,” Times of Zambia, Oct. 1, 2011.

39 Davies, The Other Face.

40 Mukuka interview.

41 Matt Wells, “China in Zambia: Trouble Down in the Mines” Huff Post World, Nov. 21, 2011.

42 Undermining Development?: 14-15.

43 “China in Zambia: from Comrades to Capitalists?” World News Review, October, 2008.

44 Jean-Christophe Servant, “Mined Out in Zambia,” Le Monde Diplomatique, May 9, 2009.

45 Kevin van Niekerk, “Facing and Overcoming Challenges, Discover Zambia v. 5: 24-29.

46 See posts 12 and 25 to “FQM, Zambia’s Largest Copper Producer, Happy with President Sata’s Drive, Lusaka Times, Oct. 13, 2011.

47 Davies, The Other Face.

48 Mukuka interview.

49 Mukuka interview.

50 Crispin Matenga, “The Impact of the Global Financial and Economic Crisis on Job Losses and Conditions of Work in the Mining Sector in Zambia,” ILO, Lusaka, 2010; Charles Muchimba, “The Zambian Mining Industry: a Status Report Ten Years after Privatization,” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Lusaka, 2010: 27.

51 “African Union to Tackle Human Rights Abuses of Mineworkers”, Coal Mountain, Oct. 25, 2010.

52 See, e.g., Ching Kwan Lee, “Raw Encounters: Chinese Managers, African Workers and the Politics of Casualization in Africa’s Chinese Enclaves,” China Quarterly) 199 (2009): 647-699; Dan Haglund, “In it for the Long Term? Governance and Learning among Chinese Investors in Zambia’s Copper Sector,” CQ 199 (2009): 627-646.

53 “Clinton Warns Africa of China’s Economic Embrace,” Reuters, June 11, 2011; “David Cameron Warns Africans about ‘Chinese Invasion’ as they Pour Billions into Continent,” Daily Mail (UK), July 20, 2011.

54 “We are Here to Stay: China,” Daily Mail (Zambia), Nov. 10, 2011.

55 Action for Southern Africa, et al., “Undermining Development? Copper Mining in Zambia,” Oct. 2007.

56 Counter Balance, “The Mopani Copper Mine, Zambia: How European Development Money has Fed a Mining Scandal”, Dec. 2010: 16-17.

57 Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, Troubling the Waters: Black-Jewish Relations in the American Century (Princeton University Press, 2010):223.