Documenting Urban Indigeneity: TOKYO Ainu and the 2011 survey on the living conditions of Ainu outside Hokkaido

Simon Cotterill

Abstract

If acknowledged at all, Japan’s indigenous population the Ainu are usually represented as a rural, exotic group, bound to ancestral homes in Hokkaido and the Northern territories. Yet, large numbers of Ainu, perhaps even the majority of their population, now live in urban centres outside Hokkaido. The recent documentary TOKYO Ainu challenges traditional, detrimental representations of Ainu culture as solely rural and sedentary, and records the complex contemporaneous reality of urban indigeneity lived by those Ainu within Greater Tokyo. This article firstly reports the main themes of the film. It then compares the relative success of TOKYO Ainu in broadening discourse and understanding of Ainu identity to the Japanese government’s recent living conditions survey released this year.

© TOKYO Ainu Film Production Committee: No part shall be reproduced or reused with permission of the Committee. |

Japan’s indigenous population the Ainu are usually represented as a rural, exotic group, bound to ancestral homes in Hokkaido and the Northern territories. Yet, this narrow discursive frame ignores the 5000 to 10000 Ainu who live in Tokyo and the surrounding Kanto region (Greater Tokyo),1 as well as those who live elsewhere on the mainland. While a government survey found 23,782 Ainu inside Hokkaido in 2006,2 some commentators, including the late Umesao Tadao, founding president of the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, now estimate their population outside Hokkaido to exceed that number.3

Modern depictions of the Ainu as a rural “(post-) hunter-gatherer people” and of their identity as absolutely conflated with Hokkaido have been described by Watson as a “detriment to the large number of Ainu who live in urban centres on the mainland.”4 A new documentary, TOKYO Ainu, challenges these engrained representations and emphasises the existence of Japan’s indigenous people within its capital city. The film charts the urban migration of Ainu elders from Hokkaido to Greater Tokyo; and, while preserving their voices for future Ainu generations, it also documents the contemporaneous reality of urban indigeneity lived by them, their children and grandchildren in the Kanto region today.

© TOKYO Ainu Film Production Committee: No part shall be reproduced or reused with permission of the Committee. |

After briefly outlining the context of “Ainu-Japanese” relations in which TOKYO Ainu has been made and providing a short background history of the Ainu in the Kanto region, this article introduces the main themes of the documentary. TOKYO Ainu successfully records the myriad experiences of urban Ainu within a compact and cohesive narrative. Its success contrasts sharply with a Japanese government survey also published this year. This survey, the Hokkaidogai Ainu no seikatsu jittai chousa,5 attempts to report on the living conditions of Ainu outside Hokkaido; however, its methodology has been criticised by Ainu within the Kanto region and its poor response rate reveals enduring problems with the state’s approach to the Ainu.

Background

Fuller accounts of Ainu history, which includes years of their existence being denied and ignored by the Japanese government and the recent official acknowledgement of their indigenous status in 2008 can be found elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific Journal; as well as discussion of the Ainu’s place within contemporary national and international discourse (See Burgess,6 Winchester,7 lewallen,8 Dubreuil,9 and Cotterill10). Here, only a brief history of the Ainu in Greater Tokyo will be provided:

There have been Ainu within the Kanto for more than one hundred years. In 1872, four years after the Meiji Restoration and three after the new government founded its Hokkaido Development Commission to annex the island, a Hokkaido Aboriginal Training School was established in Minato-Ku, Tokyo and thirty-eight Ainu were forcibly brought from their northern homes to study at the school, five of whom died there. Within Zojoji Temple11 in present-day Shiba Park, the school tested educational methods that the Meiji government would later use to assimilate young Ainu in Hokkaido to Japanese culture.

|

An icarpa ceremony in commemoration of the five Ainu who died when forced to attend the Hokkaido Native Training School has been held annually in Shiba Park, Tokyo since 2003. |

In 1899, as the Japanese state sought to impose its own lifestyles and ideologies on people in its colonies, the Former Hokkaido Natives Protection Act was enforced.12 Under the act, compulsory and segregated Japanese-language education was imposed on all Ainu children,13 their own language was banned, and their parents were prohibited from practising traditional activities necessary for their economic survival, as the government tried to change the Ainu from hunters and fishers into farmers.14 The Meiji government’s attempts to assimilate and bury Ainu culture also included legal prohibitions concerning their physical appearance and customs.15 In the face of these prohibitions and heavy discrimination in Hokkaido,16 many Ainu left their homes to seek solace and employment in the anonymity of Honshu’s cities. Then, after 1945, the Japanese government used Hokkaido to relocate many Japanese returning from the colonies,17 increasing the discrimination and competition the Ainu faced for employment, and creating a second wave of southward immigration during the 1950s.

In 1964, the first18 association of Ainu in the Kanto was founded. Pewre Utari, meaning “young friends”, developed out of interaction between young Japanese and Ainu in the region. Then, in 1972, a letter entitled Let’s Unite, Ainu Brothers and Sisters, written by Ukaji Shizue, appeared in the Asahi Shinbun.19 This led Ukaji to form the Tokyo Utari Association and petitioning the government for funds to conduct a socioeconomic survey of Ainu in the capital20 as well as for funds to construct facilities for the Ainu there.21 In 1974, the first survey of Ainu outside Hokkaido was conducted in Tokyo. It revealed conditions such as poor access to education, inadequate housing, and discrimination amongst 679 self-identifying Ainu. In response, the Metropolitan Government appointed one Greater Tokyo Ainu woman to be a counsellor for other Ainu in the region.

While the results of the survey and the minimal action taken by the government helped to galvanise some Ainu, a swift turnover of volunteers made it difficult to implement their plans.22 In 1980, a new group, the Kanto Utari Association was formed for the purpose of increasing friendship among Ainu families in Greater Tokyo; then, three years later the Rera Association was formed, which eventually led to the first Ainu restaurant in Tokyo.23 In 1988 another Tokyo survey was conducted. This time there were 1,134 respondents, upon which basis the total Ainu population of Tokyo was estimated to be around 2,700. Yet, despite revealing similar poor living conditions to the first survey, no action was taken by the government.24

The restaurant, Rera Cise, which means ‘House of Wind’ in the Ainu language, opened in Waseda in 1994 and moved to Nakano in 2000. Its proprietors hoped it would help to spread Ainu culture “like the wind.”25 Before closing in 2009, it served a traditional Ainu menu to Ainu and non-Ainu customers, and hosted performances of Icarpa, an Ainu ceremony commemorating ancestors.26 Rera Cise put on monthly ceremonies and talks and allowed Ainu in Tokyo the chance “to foster and experience their indigenous identity, sometimes for the first time.”27 (A new Ainu restaurant recently opened in Tokyo, owned by the son and daughter of a former Rera Association member.)28

In 1998, a Tokyo group called the Ainu International Network presented a statement to the 16th session of the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations in Geneva. This statement recalled the history of their economic migration from Hokkaido and the discrimination they faced. Ainu from the Kanto region remained involved as the Hokkaido Ainu Association took the lead in diplomatic exchanges with the UN and the Japanese government. These triangular relations, within which international pressure on the government played a significant role,29 eventually led to the 1997 Ainu Cultural Promotion Act and repeal of the Former Hokkaido Aborigine Protection Act. As part of the new policy, the Ainu Culture Centre was established in 1997 in Yaesu, near Tokyo Station. It serves as a meeting place and provides classes in Ainu language, embroidery, and wood carving. However, as it is basically an office space, many Ainu in Greater Tokyo have complained that it cannot flexibly meet their needs and have called for provision of a more suitable facility.30

In 2008, the Japanese Diet’s long overdue decision to acknowledge the Ainu’s status as indigenous to Japan was preceded by a Greater Tokyo Ainu Cultural Festival and a demonstration in Nagatachou, Tokyo’s political district, which helped to build pressure on the government. The Diet’s decision was also preceded by a 2008 signature campaign conducted by the Ainu Utari Liaison Committee, an umbrella organisation for Ainu groups in the Kanto, headed at the time by Mikiko Maruko and now led by Shizue Ukaji. The campaign requested the government to protect the indigenous rights of the Ainu.31

|

May 2008, Ainu Demonstration in Nagatachou, Tokyo |

TOKYO Ainu

Ukaji Shizue had ardently wished for a film about the Ainu in Greater Tokyo since she began advocacy of their issues in 1972. Mother of established actor Ukaji Takashi, she felt “such film making would inevitably bring fellow Ainu face to face with one another”.32 Alongside her brother Urakawa Haruzo, Ukaji tried to inteest other Ainu in a project to produce a film ‘of the Ainu, by the Ainu, for the Ainu’, but none were ready and able to take the lead.

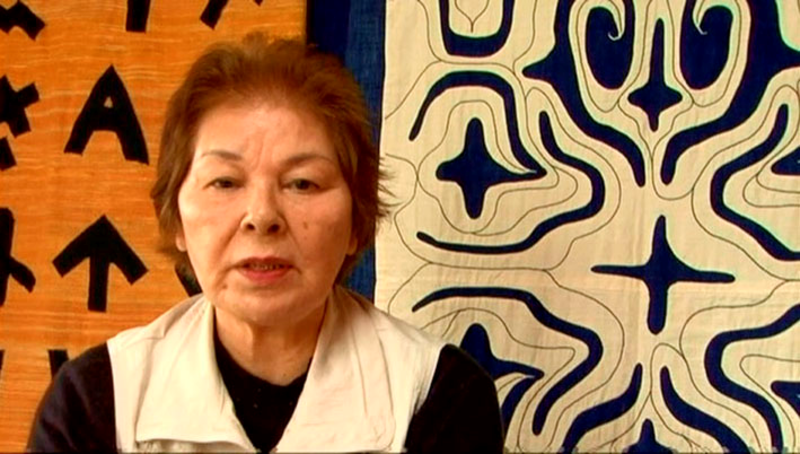

|

Ukaji Shizue, Shinjuku |

Eventually, however, her impassioned plea – “Make an Ainu movie for us! Please document our voices for future generations!” – reached Moriya Hiroshi, a non-Ainu Japanese documentary maker through producer Sato Maoki. TOKYO Ainu’s director, cinematographer, and editor, Moriya had formerly worked for national television network TBS, where he directed successful programmes about indigenous peoples and wild animals on five continents. His documentary The Philosophers of the Forest, the Mehinaku about indigenous people of the Amazon Rainforest received a High Vision Award in 2000 before Moriya left TBS to work as a freelance director. He was also vegetable farming from his Tokyo home, when he learned about Kamuymintar, an Ainu cultural facility being built by Urakawa Haruzo. Despite having practically no knowledge of the Ainu, Moriya took on the challenge of making the film and TOKYO Ainu began shooting in August 2007.

Originally, the documentary intended to record the story of Urakawa, who had previously won an award for his work preserving and demonstrating Ainu culture in Greater Tokyo, and was single-handedly building Kamuymintar in Kimitsu, Chiba.33 Moriya began following Urakawa, while thinking about what shape the film would eventually take. Amongst the first images shot were scenes of Urakawa at the Tokyo icarpa ceremony held to commemorate Ainu who had died when brought from Hokkaido to Tokyo for re-education in 1872. The event was the first time that Moriya had seen many of the Ainu who live in Greater Tokyo gathering together, and he says that this “was the moment when the picture of the Ainu in [his] mind expanded from a single person of Urakawa Haruzo to the Ainu community.”34 From this point TOKYO Ainu expanded into an attempt to document the diverse lives and experiences of the many Ainu within the Kanto region.

Three rules governed Moriya’s production of TOKYO Ainu – “no narration, no background music, and no ready answers.” He applied these rules in order to foreground the Ainu’s own voices and for it to be these that move the audience, rather than any emotive, cinematic techniques. Filming took three and a half years and 180 hours of footage was recorded on DV tape. The completed 116-minute documentary contains the voices of numerous older Ainu who migrated from Hokkaido to the Kanto region between the 1950s and 70s. Alongside interviews with these fuci and ekasi (honorific Ainu terms for elder women and men), TOKYO Ainu features the stories of younger Ainu born in Greater Tokyo and scenes of them performing traditional Ainu dance. While the film has no background music, the live sound of these dance scenes instils the narrative with an energy that complements the compelling interviews.

|

Urakawa Haruzo near the iconic Fuji TV building, Odaiba, Tokyo |

At the heart of TOKYO Ainu are Urakawa Haruzo and Ukaji Shizue. The documentary starts with Urakawa driving and Ukaji walking through Tokyo. Iconic images of Rainbow Bridge, Shinjuku, and Tokyo Tower are shown, as the film sets out to emphasise the existence of Ainu in the capital. Moriya’s camera then moves to a Kamuynomi ceremony taking place just outside Yokohama’s famous Nissan Stadium. Kamuy means ‘deities’ and nomi means ‘pray’ and the ceremonies precede all important Ainu occasions. The Kamuynomi appears alongside images of Ainu cooking, embroidering, dancing and music-making, Moriya uses the opening sequence to emphasise that, not only Ainu people, but also Ainu culture is present in the Kanto region.

|

|

The stories of the elder Ainu’s migration to Greater Tokyo are diverse; some fuci and ekasi explain that they left reluctantly out of financial necessity, while others left to avoid discrimination. Of life back in Hokkaido in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, Urakawa Haruzo says “there were good times and bad times.” But other Ainu tell of a much harder life. Shimada Akemi, now the Secretary General of the Ainu Utari Liaison Committee, describes how when growing up in Hokkaido, despite their family’s own poverty, her mother often lent money to poorer Japanese neighbours; yet these neighbours still ignored her mother in public because she was Ainu.

In TOKYO Ainu, Aoki Etsuko of the Pewre Utari Association recalls strong discrimination against the Ainu in the 1960s where she grew up near Obihiro, Hokkaido. Her father died when she was five and her mother, as an Ainu, could only find work in construction. Her mother was fluent in the Ainu language, but elsewhere Aoki has described how, despite this fluency, her mother did not attempt to hand down the language to her children.35 Like many other mothers in Hokkaido at the time, confronted by extreme prejudice, she had felt that her children would have no use for their mother tongue within Japanese society.

When Aoki graduated from High School, she moved to Tokyo to avoid the severe discrimination Ainu faced when job-hunting in Hokkaido. She found work and when old enough she married a Japanese man. Aoki says “I never wanted to marry an Ainu man” as “being Ainu always meant you were under scrutiny… I was determined to spare my children the pain and anguish I had experienced growing up Ainu by diluting their blood.”36 She was not the only Ainu woman who felt this way.

|

Etsuko Aoki, wearing a sweatshirt of the band Ainu Rebels |

Aoki says when she initially arrived in Tokyo there wasn’t any discrimination “due to ignorance”. She describes even meeting girls her age from Hokkaido who knew nothing about the Ainu. However, another Ainu woman, Maruko Mikiko, states that “discrimination is worse in Honshu than Hokkaido. It’s true discrimination for being Ainu is gone. Honshu people barely know anything about the Ainu… and so in Honshu there is discrimination for looking like a foreigner or illegal foreign worker.” Aoki has written that “I thought that things would change for the better in Tokyo; however, time proved me wrong”. She was joined in Tokyo by her older brother Sakai, who also came in search of work. But, according to Aoki, he and other Ainu men could only find jobs in San’ya, a district known for day labourers. Sakai, who was an activist for Ainu rights, was regularly harassed and beaten up by the police in 1987, before his body was mysteriously found in a canal the next year.37

Ukaji Shizue, too, describes her fear of discrimination in Tokyo. Due to her exotic good looks, she worked as a door girl for a tango club. She leads the camera to an old club in Shinjuku called Ezo Palace where Ainu used to dance and perform for customers. When seeing other Ainu in busy districts like Shinjuku, she says “I would go to tap their shoulder but pulled my hands away at the last moment. I didn’t know what type of place they might be working in…they might have lost their jobs if it became known that they were Ainu.” But in the film, her brother often has a more positive view on life in the Kanto.

Born in Hokkaido in 1938, as a child Urakawa Haruzo would often baby-sit and help his family in the fields rather than go to school. He learned how to hunt from his father and became close to nature by going to pick wild plants and seaweed with his mother.38 He came to Tokyo when he was 42 because a friend had told him there was work available with wrecking crews. He then brought his family to the capital in 1985 and says “Tokyo was a good place in that you could achieve anything”. Twenty years later in 2005, Urakawa won a cultural award for his reconstruction of a cise (traditional Ainu house), in Otsuki City, Yamanashi prefecture and in TOKYO Ainu he is seen building another cultural facility, the Kamuymintar in Chiba. In one scene, a group of Japanese school children attend the centre and marvel at Urakawa’s strength as he demonstrates traditional Ainu methods of pounding millet.

|

Ainu children perform Sicocoy (dance celebrating an abundant year). |

Connecting Ainu culture with children is a major theme of TOKYO Ainu. Ainu children are seen playing and learning at the cultural centre in Yaesu, and Imai Noriko brings her children there because she wants them “to know this kind of world exists,” especially since it was something she wanted as a child but couldn’t experience. A younger Ainu couple, Shimokura Emi and Hiroyuki are interviewed in the film and say of their children that “whether they choose the Ainu path or not is their choice. What’s important is that the choice will be there”.

At times, TOKYO Ainu seems to reveal a generational shift in how Ainu-ness and difference is viewed within Japan and by Ainu themselves. Ishikawa Kyoko grew up embarrassed about the fact she was half Ainu and was reluctant to tell her daughter. Yet, when her daughter found out, her response was “that means I’m a quarter… chou kakkoi! (very cool!).” Ishikawa says, “I was surprised she took it that way.”

|

Shimokura Emi and Hiroyuki |

While TOKYO Ainu is predominantly a record of elder Ainu voices, there are nods to Ainu youth. During her interview, Aoki Etsuko wears a sweatshirt bearing the name of a performance group, Ainu Rebels, who played traditional Ainu instruments such as the mukkuri, while rapping and arranging traditional dance steps to hip-hop beats. The group’s former leader Mina Sakai claimed “we think that culture is something that constantly changes.”39

Within TOKYO Ainu there are indications that some of these younger Ainu will move towards less traditional ways of expressing their culture and away from involvement in the various associations of Ainu around the region. Shimokura Emi and Hiroyuki are designers and silversmiths who run the jewellery shop Ague in Nakano, Tokyo. They incorporate Ainu patterns and symbols within modern jewellery designs.40 Emi says, “an Ainu is Ainu even if he or she doesn’t mix with other Ainu. That doesn’t stop you from being Ainu.”

Video of Ague’s jewellery

The 2011 Survey on the Living Conditions of Ainu outside Hokkaido

In 2008, alongside its acknowledgement of their indigenous status, the Japanese government convened an expert panel to consider policies related to the Ainu. The panel met ten times during the next year,41 and finally produced a report showing tjat the educational attainment rates of Ainu in Hokkaido were lower than the Japanese average, while the proportion of Ainu receiving ‘livelihood protection’ benefits was higher.42 The report was followed by certain welfare measures for the Ainu being adopted by the regional government, while the final report also acknowledged the need for research into the living standards of Ainu living in the rest of Japan.

The ‘expert panel’, which had included only one Ainu member, was replaced in December 2009 by an Ainu Policy Promotion Panel, which currently contains five Ainu, predominantly from the Hokkaido Ainu Association.43 Rather than contacting the Kanto-based Ainu associations that had helped organise the Tokyo Metropolitan Government surveys in 1974 and 1988, the panel conducted its 2011 living conditions survey of Ainu outside Hokkaido with the sole official assistance of the Hokkaido Ainu Association.44 First, Ainu outside Hokkaido known to the association were identified, and then others were reached through telephone enquiries, at times conducted by non-Ainu. In all, 241 households and 318 individuals were found and then surveyed by post, with questionnaires sent out on 22nd December 2010.45

This number of Ainu households approached by the national survey is significantly fewer than the 401 and 406 households respectively surveyed by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 1974 and 1988, despite the supposedly narrower focus of these surveys. Furthermore, only 63.5% of these 241 households and only 66% of the 318 individuals initially identified actually responded in time for the 25th January 2011 deadline set by the panel.46

Shimada Akemi, Secretary General of the Ainu Utari Liaison Committee, has explained some of the problems with the Ainu Policy Promotion Panel’s survey methodology: “I was confident that the survey would not be successful if Ainu were to be approached by mail and phone”, she said at a meeting on 22nd October 2011.47 The Ainu Utari Liaison Committee told some of the panel members involved in the survey that their approach did not take into account the feelings of those Ainu who were afraid of coming out as Ainu. But the panel members told the committee that the survey would be carried out according to the methods they had decided on.48

|

A forum on Ainu Issues, 22nd October 2011 |

In the 2011 publication of the survey, the Ainu Policy Promotion Panel explain their belief that research into the Ainu outside Hokkaido should be toumei, transparent.49 This echoes the call for transparency by the expert panel in their 2009 report.50 However, such emphasis on transparency necessitates an approach which ignores the ambiguous feelings most Ainu have about their identity after years of discrimination.

Of the second Tokyo survey in 1988, Shimada says

“I was very reluctant to reveal my Ainu identity at that time, but I responded to the survey as I was approached by Ainu interviewers. I had coffee and cakes ready and waited for them as they were the first Ainu I had ever met since I moved to Kanagawa Prefecture. I was glad to meet fellow Ainu and agreed to be interviewed, although I told them I had no intention of getting involved in Ainu issues. If I had been approached only by mail and phone or an interviewer had been non-Ainu, I would not have agreed to be surveyed.”51

|

Shimada Akemi |

Not only did the panel approach many Ainu in the wrong way but, through only using the Hokkaido Ainu Association, they failed to find many self-acknowledging Ainu who might well have responded to their questions. Shimada herself did respond, but many of her more than sixty relatives in Greater Tokyo were not approached by the panel at all.52

Its lack of respondents notwithstanding, the survey on the living conditions of Ainu outside Hokkaido, published on 24th June 2011, did contain some noteworthy findings:

The largest number of Ainu households surveyed were found in Tokyo (40), followed by Kanagawa (21), Shizuoka (17), Chiba (16), Saitama (14) and Aichi (12). The majority of Ainu outside Hokkaido, 28.1%, were in single-person households, which contrasts with those in Hokkaido who mostly live in households of two to four persons. Additionally, while 54.3% of Ainu in Hokkaido own land, the majority of Ainu outside Hokkaido rent apartments.53

Among Ainu households outside Hokkaido, 44.8% live on less than three million yen per year, compared to 50.9% in Hokkaido,54 and 33.2% of all households in Japan.55 7.6% of the Ainu included in the 2011 survey were receiving ‘livelihood protection’ welfare from the state, compared to the 2008 national average of 2.3%.56

Of the individuals surveyed, almost 20% had not told their spouses that they were Ainu, for reasons ranging from not having a strong sense of their own Ainu identity to fearing that disclosing their heritage would worsen their relationship.57 Almost 40% of those surveyed had not told their friends or neighbours that they were Ainu.58 65.2% of the Ainu told their children that they were Ainu, while 34.8% did not; some of these feared their children would be discriminated against.59

|

Ukaji Shizue |

Conclusion

Shimada Akemi believes that despite methodological problems, the Ainu Policy Promotion Panel’s survey could be helpful for the Ainu living outside Hokkaido, were its results to be incorporated in a national Ainu policy allowing them to receive equal treatment to Hokkaido Ainu.60 However, it seems possible that the small number of Ainu identified by the panel could also be used as an excuse to keep the situation of Ainu outside Hokkaido relatively low on the political agenda.

Some tensions clearly exist among groups representing Ainu in Greater Tokyo and between these groups and the Hokkaido Ainu Association. In one of TOKYO Ainu’s final scenes, Ukaji Shizue is seen walking with Sawai Aku of the Association. She complains to him that “Ainu shouldn’t discriminate against each other.” She also explains that many previous Ainu movements were “crippled by jealousy and other internal problems, so that over the past several decades we haven’t been able to gather our voices to make demands to the government.”

While there still seems some way to go before the government effectively addresses the Ainu’s situation in an appropriately nuanced way, cultural works such as TOKYO Ainu will at least allow the Ainu outside Hokkaido to gather, communicate with one another, and make their voices heard.

TOKYO Ainu, promotional video (c) TOKYO Ainu

Details (in Japanese an English) about TOKYO Ainu screenings around Japan can be found here.

Screening of TOKYO Ainu with English Subtitles

Date and time: 23 November 13:00 to 15:00

Venue: Space Alta (tel & fax:045-472-6349)

Charge: 1,800 yen at the door, 1,500 yen in advance

Simon Cotterill is a recent graduate from the University of Oxford’s Nissan Institute.

Recommended citation: Simon Cotterill, ‘Documenting Urban Indigeneity: TOKYO Ainu and the 2011 survey on the living conditions of Ainu outside Hokkaido,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 45 No 2, November 7, 2011.

Articles on related subjects

• Mark Winchester, Everything you know about Ainu is wrong: Kobayashi Yoshinori’s excursion into Ainu historiography

• Simon Cotterill, Ainu Success: the Political and Cultural Achievements of Japan’s Indigenous Minority

• Mark Winchester, On the Dawn of a New National Ainu Policy: The “‘Ainu’ as a Situation” Today

• Katsuya HIRANO, The Politics of Colonial Translation: On the Narrative of the Ainu as a “Vanishing Ethnicity”

• ann-elise lewallen, Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir

• Chisato “Kitty” O. Dubreuil, The Ainu and Their Culture: A Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment

Notes

1 TOKYO Ainu

2 The Ainu Association of Hokkaido (2010) Actual Living Conditions of the Hokkaido Ainu

3 Umesao T, Ishii Y, 1999, “Taminzoku no kyo. zon ni mukete shiso. no o. kina tenkan o” [Transforming thought: towards multiethnic coexistence], in Nihonjin to Tabunkashugi [The Japanese and multiculturalism], (Eds)Y Ishii, M Yamauchi (Yamagawa Shuppansha, Tokyo) pp 195 – 241 in Watson, M.K. (2010) Diasporic Indigeneity: place and the articulation of Ainu identity in Tokyo, Japan, Environment and Planning A, volume 42, pages 268 – 284

4 Watson, M.K. (2010) Diasporic Indigeneity: place and the articulation of Ainu identity in Tokyo, Japan, Environment and Planning A, volume 42, pages 268 – 284

5 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査

6 Burgess, C. (2010) The ‘Illusion’ of Homogeneous Japan and National Character: Discourse as a Tool to Transcend the ‘Myth’ vs. ‘Reality’ Binary

7 Winchester, M. (2009) On The Dawn of a New National Ainu Policy: The “Ainu” as a Situation Today, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 21-3-09, October 12

8 lewallen, a.e. (2008) Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 48-6-08, November 30

9 Dubreuil, C. O. (2007) The Ainu and Their Culture: A Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment, The Asia-Pacific Journal

10 Cotterill, S. (2011) Ainu Success: the Political and Cultural Achievements of Japan’s Indigenous Minority, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 9, Issue 12, No 2, March 21

11 Hilger, I. (1967) op.cit.

12 Rabson, S. (1996) Assimilation Policy in Okinawa: Promotion, Resistance, and ‘Reconciliation’ Japan Policy Research Institute Occasional Paper No. 8, October 1996

13 Sjöberg, K. (1993) The Return of the Ainu: Cultural Mobilisation and Practice of Ethnicity in Japan, p. 128. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers

14 Rabson, S. (1996) op. cit.

15 Wilhelm, G. (2009) The Ainu in Japan: Ethnic Identity and Cultural Definitions

16 Mock, J. (1999) Culture, Community and Change in a Sapporo Neighbourhood, 1925 – 1988, p. 83. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press

17 Mock, J. (1999) op. cit.

18 TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers (2011) Distributed at screenings

19 TOKYO Ainu

20 Watson, M.K. (2010) op. cit.

21 TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers (2011)

22 Watson, M.K. (2010) op. cit.

23 TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers (2011)

24 Watson, M.K. (2010) op. cit.

25 Cotterill, S. (2011) op.cit.

26 TOKYO Ainu

27 Watson, M.K. (2010) op. cit.

28 ハルコロ(2011)

29 Cotterill, S. (2011) op. cit.

30 TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers (2011)

31 TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers (2011)

32 Ukaji, S. (2011) A Film by the Ainu for the Ainu – My Dream, in TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers

33 Foundation for Research and Preservation of Ainu Culture (2005) Ainu Cultural Award

34 Moriya, H. (2011) Weaving the Voices I Heard in TOKYO Ainu: Information Pamphlet for Viewers

35 Aoki, E., Kitahara, K., Shigeru, K., Kaizawa, K., (2006) Voices of Resilience and Resistance in Kunnie, J.E. and Goduka, N.I. (eds) Indigenous Peoples’ Wisdom And Power: Affirming Our Knowledge Through Narratives, Vitality of Indigenous Religions Series, Ashgate Publishing Company

36 Aoki, E., Kitahara, K., Shigeru, K., Kaizawa, K., (2006) op. cit.

37 Aoki, E., Kitahara, K., Shigeru, K., Kaizawa, K., (2006) op. cit.

38 Ainu Pride Productions (2011) Biographical information accompanying details of Workshop with Haruzo Urakawa at Meiji University

39 Reuters (2007) Japan’s Ainu Fuse Tradition, Hip-Hop for Awareness

41 アイヌ政策のあり方に関する有識者懇談会(2009) 開催状況

42 アイヌ政策のあり方に関する有識者懇談会 (2009) 報告書平成21年7月

43 アイヌ政策推進会議 (2011) 構成員名簿

44 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査p.2

45 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査pp.2-3

46 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査pp.2-3

47 Comments collected at a forum on Ainu issues, 22nd October 2011

48 Comments collected at a forum on Ainu issues, 22nd October 2011

49 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 政策の対象者を認定する場合に必要な手続き等について p.39

50 アイヌ政策のあり方に関する有識者懇談会 (2009) 報告書平成21年7月 p.39

51 Comments collected at a forum on Ainu issues, 22nd October 2011

52 Comments collected at a forum on Ainu issues, 22nd October 2011

53 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査p.8

54 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査p.9

55 厚生労働省(2009) 国民生活基礎調査

56 総務省(2011) 社会生活統計指標

57 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査 p.25

58 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査 p.26

59 アイヌ政策推進会議(2011) 北海道外アイヌの生活実態調査 p.26

60 Comments collected at a forum on Ainu issues, 22nd October 2011