War and Nationalism in Yamato: Trauma and Forgetting the Postwar

Aaron Gerow

The recent spate of Japanese films dealing with World War II or with Japan fighting modern wars raises questions about what kind of histories are being narrated, both wartime and postwar, what they say about Japanese responsibility for war and atrocities in the Asia-Pacific War, and how they relate to current trends in nationalism. The fear is that such movies resonate with other phenomena, from the comments of Japanese officials, most recently exemplified by the speeches and writings of retired General Tamogami Toshio, Japan’s former Air Self-Defense Force [ASDF] Chief of Staff, to popular manga like Kobayashi Yoshinori’s work, that seem to legitimize Japan’s pursuit of war in East Asia and deny Japanese responsibility for atrocities.1 I have already argued in Japan Focus, with regard to two cinematic imaginations of Japan at war, the alternative World War II history Lorelei (Rōrerai, Higuchi Shinji, 2005), and the Maritime Self-Defense Forces mutiny movie, Aegis (Bōkoku no ījisu, Sakamoto Junji, 2005), that such fears of a rising revisionist nationalism in cinema are not always justified.2 Both works present a “victorious” Japan, populated by young people willing to sacrifice themselves for their community, but through an entertainment cinema that appears so conscious of a consumer base with conflicting opinions about the war and nationalism, that it attempts to construct a hegemonic vision of the nation that appeals to all sides, only to end up portraying an empty Japan that can mean anything to anyone.

One could argue that this emptiness is a product of the fact that these films, both of which are fantasies, do not carry the burden of the real memory of WWII and its aftermath. What of the recent films that take up actual historical moments and figures, such as kamikaze pilots or other suicidal missions? Yamato (Otokotachi no Yamato, 2005), for instance, about the final days of the famed battleship, was a significant box office success, grossing ¥5.1 billion in ticket sales, the fifth best selling Japanese film in a year when Japanese movies out-grossed foreign films for the first time since 1985 (it was also the most successful Japanese war film in decades).

Advertisement: Yamato “rattles the soul” |

Yoshikuni Igarashi has argued that post-2000 kamikaze films such as Fireflies (Hotaru, 2001) respond to the end of the Shōwa Era and the Cold War by moving away from narratives that previously marked a division between the war and the postwar by depicting the heroic deaths of the kamikaze, as if their demise signified the end of the war and its problems. Newer films are considering the lingering traumatic effects of the war on postwar Japan in the form of surviving kamikaze.3 I contend, however, that the effect of many of these films is to engage not their manifest subjects, the post-1989 present or even the wartime, but the problematic, usually unrepresented history in between. Igarashi argues that Fireflies avoids dealing with the trauma of the war by narrating a second set of deaths in the present, which cleanly conclude the postwar and divide it from today. I contend that Yamato, on the other hand, which offers no such deaths, performs wartime trauma in a vicarious fashion, using the disruptive effects of depicting WWII trauma so as to divert the audience’s attention away from what might be for the majority of the audience, born after the war ended, the greater trauma: the postwar era and its history of economic upheaval, American bases, student protest, or “democracy.” That these films are also appearing at the time of the “Shōwa 30s” boom, featuring nostalgic narratives of Japan between 1955 and 1965 such as the successful film series Always—Sunset on Third Street, is no coincidence. Some films ignore the war and the long history of postwar conflict to construct an idyllic postwar, while others “remember” wartime trauma in order to skip to a present where that trauma has been solved. Both, however, construct a postwar empty of problems in order to avoid dealing with its traumatic and divisive history, primarily in order to establish the illusion of a more unified present.

Yamato was produced by Takaiwa Tan, the chairman of Tōei, and Kadokawa Haruki, a maverick producer who in the 1970s and 1980s introduced into the Japanese film industry new marketing strategies for big-budget spectaculars. The film was Kadokawa’s return to success after his cocaine bust in 1993 and reunited him with director Satō Jun’ya, who had helmed such early Kadokawa blockbusters as Proof of the Man (Ningen no shōmei, 1976). Purportedly budgeted at 2.5 billion yen, quite high by Japanese standards, Yamato featured an all-star cast, including Nakadai Tatsuya, Sorimachi Takashi, Nakamura Shidō, Matsuyama Ken’ichi, Okuda Eiji, Suzuki Kyōka, Aoi Yū, Terajima Shinobu, and Watari Tetsuya, and a colossal set: a life-size reproduction of the front half of the Battleship Yamato, itself the largest battleship ever constructed.

Yamato narrates the last days of the famous battleship, which was sunk off Japan on 7 April 1945 with a loss of 2740 lives after being sent on a suicidal mission to defend Okinawa. It does this through two structuring devices: the first focusing on several young recruits who were only 17-years old at the time of the last battle,

Lost youth: Kamio (by the flag) and the other recruits |

and the second, a framing narrative in which one of those recruits, Kamio Katsumi, is asked sixty years later by Makiko, the daughter of Uchida Mamoru, one of his former shipmates, to take her to the site of the sinking. Both are central in articulating the film’s ambiguous, if not contradictory politics. By concentrating on the young men, the film, which was based on the award-winning book by Henmi Jun (Kadokawa Haruki’s sister), is able to narrate a tale of innocent, promising spirits needlessly sent to their grisly deaths by a central command that even the fleet commander, Itō Seiichi, registered objections to. Although the older, adult trio of Moriwaki Shōhachi, Uchida, and Karaki Masao, who are directly in charge of these young recruits, can convincingly voice their desire to sail to their deaths because of their love for Yamato (and, correspondingly, the nation it is named for) and their hope of defending their families at home, the greenhorns’ similar statements lack force and are even questioned by Moriwaki at one point. Quite a number of voices, including that of the director, claimed Yamato was an anti-war film, one revealing the horrible waste of life caused by a reckless leadership.4 Yet right-wing commentators could also point to the same chaste sailors and, especially by citing other texts like Nagabuchi Tsuyoshi’s honorific ending song, claim they were presented as an example of selfless patriotism that all Japan should follow.5

The framing structure only reinforces these possible, contradictory readings. Kamio’s narration of what happened after Yamato’s loss, especially the deaths of his girlfriend Taeko and Uchida’s lover Fumiko in the atomic attack on Hiroshima, prompts him to declare that even the hope of dying to save their families came to naught. Kamio in particular is presented as a victim of trauma after the war, unproductive (without wife or children) and reclusive (he did not even know Uchida had survived the Yamato sinking), whose problematic relation to memory is exemplified both by his refusal to take part in Yamato memorials, and a physical debilitation (a heart ailment) that worsens as the site of his traumatic experience nears. Coupled with Uchida, who was presumably rendered sterile by the war (his children are all adopted), Kamio represents the loss of the masculine bravura that Moriwaki and Uchida exemplified during the war.

The present-day narrative is supposed to show the overcoming of such trauma, and, like films in a similar vein, such as Titanic and Saving Private Ryan, makes Yamato a film that combines ostensibly accurate spectacles of past events with the work of processing memory for contemporary purposes. Perhaps it belongs in the “trauma cinema” that E. Ann Kaplan, Joshua Hirsch, Janet Walker, and others have discussed.6 One would initially think not, however. Given that mental trauma is usually theorized as coming from an experience so shocking and forceful that normal psychological structures are unable to manage it, thus leaving the traumatic memory in the mind unprocessed and occasionally able to wreak havoc, many have labeled trauma cinema those motion pictures which deal with experiences so overwhelming that normal modes of film, particularly the classical realism of Hollywood, cannot properly deal with it. Prominent examples of trauma cinema are then films like Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog that are modernist in form, which evince in their disjunctive cinematic structures both symptoms of the rupturing effects of trauma, as well as innovative methods of representing experiences that are inherently difficult to represent. Yamato, however, as many critics noted, even when judging it favorably, is largely conventional, if not clichéd in style. The form it relies on is not just the war film, but the television history program, since it features both the familiar voice of TV Asahi announcer Watanabe Noritsugu as the narrator, and the explanatory titles common to Japanese television documentaries and historical dramas. Actually starting with documentary footage and images of the Yamato Museum in Kure, Yamato manages a loss that, at least in terms of its own film form is not hard to represent, that has already been memorialized in conventional ways. In some ways, it is simply a reminder for those who haven’t gone to the museum.

That, however, does not account either for the film’s pretensions or its effects and popularity. Uchida’s daughter, Makiko, visits the Yamato Museum at the beginning, but must go further to the spot where the Yamato sank.

Makiko’s visit to the Yamato Museum in Kure is not enough |

Yet this is a place where there is nothing, not a trace of the ship or the event. The film must fill in for such absences. Nakamura Hideyuki has argued, both with regard to kamikaze films in general and Yamato in particular, that such works function as ceremony, representing those on suicide missions as essentially divine.7 Makiko, Kamio, and even the 15-year-old deckhand Atsushi thus travel to this place of nothingness because the odyssey itself ceremoniously honors the dead. The fishing boat’s journey is also ostensibly therapeutic, since it is directed not just at the honored dead, but also at the troubled living; not just at a heroic past, but at a crippled present. Narratively, the voyage to this location is the occasion for Kamio’s remembrances, with the authentic geography working to double their veracity. What specifically triggers his recollections is photography: the portrait of Moriwaki, Uchida, and Karaki that Makiko shows him.

A photograph of Karaki, Uchida, and Moriwaki summons the past |

And just as the photo introduces his exploration of the past, so Yamato the film similarly offers itself to the audience as a privileged means of not only accompanying the travellers on this authentic journey, but also obtaining unique access to the truth of the traumatic event. If the trip helps cure Kamio, so should it—and the movie–presumably help Japanese audiences manage a problematic history.

Before considering how it does that, we must ask what it is that the film ostensibly cures them of. One can debate whether the trauma of WWII and Japan’s defeat is still felt, over sixty years after the fact, with an audience that was mostly not alive at the time and, we are repeatedly told, not fully educated about those events. What is more important is that the film itself cites no such problem for average Japanese. Even their representatives on the boat, Makiko and the 15-year-old deckhand Atsushi, fail to speak of haunting memories that require resolution. Perhaps theirs is not a narrative of trauma, but a coming of age journey: through Atsushi, the adolescents who boarded Yamato (at the same age as Atsushi) but who could not grow up can finally become adult, largely, as with Makiko, by discovering the identity of the absent father. The question is how the audience is supposedly inserted into these larger issues. Recent Japanese war films, I have argued, share the difficulty of linking individual narratives to the collective. Yamato also bears this problem, but attempts to overcome it through what I call vicarious trauma.

Yamato was in some ways a traumatic film for spectators, too. Viewer comments on Yahoo Japan and other sites often describe the difficulty of speaking or communicating after the film, as if aphasia was one of its effects. What tends to be shocking is less the general narrative of the loss of the Yamato, than the way the innocent young recruits are killed through quite graphic cinematic representation.

A vicariously traumatic depiction of young deaths |

The gore exceeds narrative necessity, and while it might somewhat be justified thematically if the film is anti-war, it is a brutal form of filmmaking that can be cruel both to its characters and its audience. To begin with, the violence can function to collectivize Kamio’s individual trauma, to form a national experience that is epitomized by the salute of three generations to the honored dead at the end of the film.

Makiko, Kamio, and Atsushi salute the nation’s dead |

As a disruptive phenomenon, however, trauma helps disguise the inherent differences between these generations. For while Kamio’s trauma is rooted not just in the meaningless loss of young lives, but in the guilt over surviving and the powerlessness to alter history—his problem is precisely linear, based in the inability to turn back the clock—the spectator’s trauma is circular because it refers to itself and allows for revisiting. The film touts its ability to access the source of trauma just as it offers viewers the chance to relive it multiple times, even during the same viewing. This is a different form of vicarious trauma than the one described by Joshua Hirsch, who valorizes some cinema as “a traumatic relay,” actually transmitting, sometimes in analogous form, aspects of the original traumatic experience.7 There might be an element of this in Yamato, but here the vicariousness functions more as an indirect substitute than as empathic identification, one that allows spectators to experience trauma in a safe, detached circularity. This is confirmed at the end of the film, which after giving audiences a strong emotional experience, allows them to remember and memorialize it only minutes later through slow-motion flashbacks of the same brutal battle scenes under the credits. Just as trauma reflects back on cinema itself, the process of remembering that experience is directed towards the movie. It is thus quite fitting that when Yamato became a hit, the set of the movie became a tourist attraction in the six months after the film’s release for over one million people interested in reliving their experience.9

Remembering war through its reproduction: the movie set at Onomichi |

Kamio’s trauma can only be solved by becoming similarly circular. On the personal level, it is the assertion that he has lived in order to remember and memorialize the dead. This is a common refrain in war films, but it doesn’t answer the traumatic question of why these young men died, especially in a film that minutes before questioned the meaning of their sacrifice. If Kamio lived to memorialize the dead, did they die only that so that they could be memorialized? This perverse circularity is somewhat reinforced on the collective level by the film’s quotation of the legendary statement made by Lieutenant Usubuchi Iwao10 on the Yamato the day before its final battle: that Japan can only progress through defeat, and that the Yamato’s demise was necessary for the rebirth or awakening of Japan.11 How this cause is supposed to bring about the effect is uncertain, but the paradoxical victory of Japan through defeat clearly depends on the constant reiteration of that defeat. This may be the justification for the film Yamato in a time of political and economic stagnation in Japan, but it writes a peculiar history, because linear progress can only be based on a repeated return to the past if part of that history is ruptured, dismembered, and forgotten. It takes the operations of trauma—by definition an often unprocessed, unmediated, and disruptive experience—to make this possible, and that is one of the main functions of the film’s vicarious trauma.

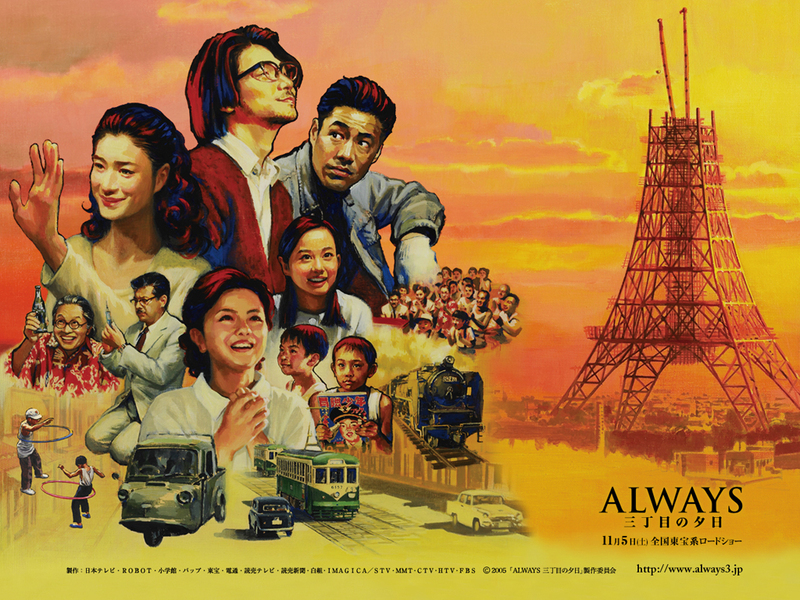

In Yamato, what is excised and forgotten is the history of postwar Japan. That is practically acknowledged by Kamio, who, at his moment of resolution, declares that for him the Shōwa era is finally over. He has overcome his problem with history by recalling what happened sixty years before, as if that alone is sufficient to deal with the entire problem of Shōwa, which continued until 1989. Such resolution is possible only if the postwar is rendered inconsequential or a mere reverberation of the wartime. Gone is the long-standing narrative of the postwar as return to and continuation of Taishō democracy, as the formation of a new international economic power. The erasure of the postwar is evident in how Yamato rewrites one of the emblematic moments in postwar Japanese cinema: the scene in Kurosawa Akira’s 1947 film No Regrets for Our Youth (Waga seishun ni kui nashi) where Yukie, played by Hara Setsuko, sets out during the war to tend the rice paddies belonging to her mother-in-law, despite the public approbation sparked by her husband’s execution as a political traitor. Yamato shifts this into the immediate postwar, as Kamio tends the paddies of his dead buddy Nishi’s mother not out of determination to maintain his values or to change society, but out of guilt that he and not Nishi survived. Memorable postwar transformations are morphed into postwar paralysis and impotence that supposedly last for the rest of the Shōwa era and become the focus of male melodrama—until they are to be forgotten. Next to shock, tears were the most common response reported by Yamato’s audiences, and as Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto has argued, melodrama was also a crucial narrative in immediate postwar cinema.12 But whereas 1950s cinema used the melodrama of postwar suffering as a means of forgetting wartime atrocities, Yamato, if not other recent kamikaze films as well, uses wartime suffering to forget not only Japanese war responsibility, but also a postwar increasingly defined, especially in contemporary popular culture, by emasculation and hypocrisy, or ahistorical idealization. The latter is evident in the cultural nostalgia for the “Shōwa 30s” (1955 to 1964) that peaked around 2005. In cinema, this was exemplified by the two successful “Always” films that featured a late 1950s gemeinschaft community of lower class residents of Tokyo, apparently free of the political or cultural strife that defined those years.13

Forgetful nostalgia: Always—Sunset on Third Street |

Such nostalgia for the postwar, however, should be seen not as the opposite, but as the other side of the coin of the attempt to forget or bypass the postwar, since both phenomena reveal a fundamental aversion to confronting the historical transformations and socio-political divisions that occurred in that era.

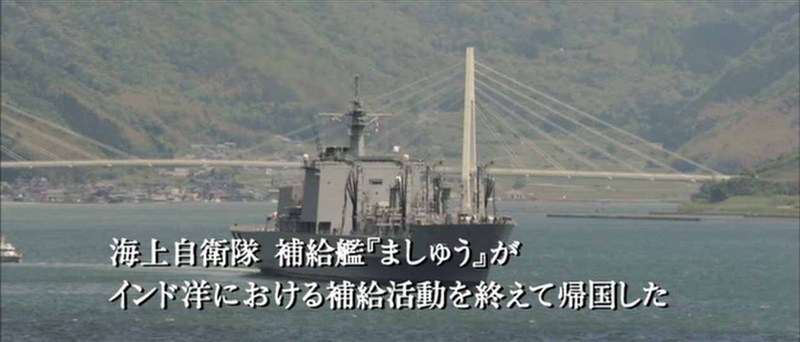

If Yamato deals with or reflects historical trauma, it is less that of the war than of the postwar; it is that history which its audience had really experienced and desired to see erased by means of the shock of defeat and the tearful eyes of Japanese masculinity. It is this trauma that the film cannot really face except through displacement, and so the postwar can only directly appear in the film through absurd plot inconsistencies (how on earth could Kamio not know Uchida had survived?) and the blatant inability to acknowledge contemporary political reality (i.e., showing MSDF ships returning from a “refueling mission in the Indian Ocean” without daring to state this is part of Japan’s support for the Iraq War).

Hidden reality: MSDF ships on a “refueling mission” |

This displacement, at least in Yamato, is rendered possible, I argue, through the deployment of vicarious trauma. By definition, trauma is an experience that has not been properly processed or mediated, that thus repeatedly returns, disrupting time and narrative. Vicarious trauma in Yamato allows spectators to share in the experience proposed by the story, while also enabling the movie to jump between past and present, in the story and in Japanese history, while avoiding the mediations and digestive processes of postwar history.

Recent war films such as Yamato certainly seek a consensus in propounding a direct link between the wartime and present-day Japan, but in the end they differ little from the empty national consensus that their more fantastic brethren rely on. Postwar trauma is to be avoided—or displaced through such techniques as vicarious trauma—precisely because of the intense divisions and turmoil it created; Yamato can only imagine a unified audience if it renders the disputes of the postwar null and void, creating an imagined community only if an empty postwar is equally imagined. That, of course, is the danger of such a text but it can also be said to be the symptom of the very postwar trauma and turmoil it tries to elide. A new history that severs and skips the postwar (just as previous histories skipped the wartime), and re-members a cycle of return between the present and the memorialized wartime, is a problematic one, especially for a film like Yamato that bears at least some anti-war pretensions. This is partially the source of its contradictory nationalism: celebrating life and survival like many other contemporary war films, yet also depending on death and defeat for its reworking of postwar history; imagining an adult Japan in the new millennium, but without being able to narrate either a history of Japan’s recovery (its becoming adult?) or its geopolitical dependency on the United States. Yamato strategically uses the ruptures of trauma to try to efface these aporia, all the while reassuring its shocked audiences with a familiar, conventional film style. Remembering is here re-membering, but with the dismembered parts of the nation, cinema and history, still poorly connected after their rearrangement.14

This is a revised version of a paper initially presented in December 2008 as part of the conference “Divided Lenses: Film and War Memory in Asia” held at Stanford University. A greatly expanded version will appear in an anthology of the conference papers, provisionally titled “Divided Lenses: Asia Pacific War Memories on Film,” edited by Chiho Sawada and Michael Berry.

Aaron Gerow is Associate Professor of Film Studies and East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University. His book, A Page of Madness came out from the Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan in 2008, and Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895-1925, was published in 2010 (the Japanese version will be coming out from the University of Tokyo Press). He also co-authored the Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies with Abe Mark Nornes (Center for Japanese Studies, 2009).

Recommended citation: Aaron Gerow, War and Nationalism in Yamato: Trauma and Forgetting the Postwar The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 9, Issue 24, No. 1, June 13, 2011.

|

Articles on related subjects • Marie Thorsten and Geoffrey M. White, Binational Pearl Harbor? Tora! Tora! Tora! and the Fate of (Trans)national Memory • James L. Huffman, Challenging Kamikaze Stereotypes: “Wings of Defeat” on the Silver Screen • David McNeill, Look Back in Anger. Filming the Nanjing Massacre • Kim Do-heong, The Kamikaze in Japanese and International Film • Susan J. Napier, World War II as Trauma, Memory and Fantasy in Japanese Animation |

Bibliography

Gerow, Aaron. “Fantasies of War and Nation in Recent Japanese Cinema.” Japan Focus (20 February 2006)

Hirsch, Joshua. Afterimage: Film, Trauma, and the Holocaust. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. “Kamikaze Today: The Search for National Heroes in Contemporary Japan.” In Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia. Eds.

Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007. 99-121.

Kaplan, E. Ann. Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in Media and Literature. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2005

Nakamura Hideyuki. “Tokkōtai hyōshōron.” In Iwanami kōza: Ajia, Taiheiyō sensō, vol. 5: Senjō no shosō. Iwanami Shoten: 2006: 301-330.

—-. “Girei toshite no tokkō eiga: Otokotachi no Yamato/Yamato no baai.” Zen’ya 7 (Spring 2006). 134-137.

Satō Kōji. “Otokotachi no Yamato o megutte: Rekishigaku no shiza kara.” Kikan sensō sekinin kenkyū 56 (Summer 2007): 74-80.

Standish, Isolde. Myth and Masculinity in the Japanese Cinema. Richmond: Curzon, 2000.

Wakakuwa Midori. “Jendā no shiten de yomitoku sengo eiga: Otokotachi no Yamato o chūshin ni.” Tōzai nanboku (2007): 6-17.

Walker, Janet. Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro. “Melodrama, Postmodernism, and Japanese Cinema,” East West Film Journal 5.1 (1991). 28–55.

Notes

1 In October 2008, General Tamogami won a lucrative prize for an essay entitled “Was Japan an Aggressor Nation?” in a contest sponsored by a construction company whose CEO has espoused rightwing views. His main arguments were that Japan was manipulated into participating in World War II by China and the United States under the influence of the Comintern, and that Japan’s reliance on America for military defense is destroying its national culture. In the ensuing controversy, he was eventually relieved of his post and pressed into retirement. Kobayashi’s manga, beginning with the notorious On War (Sensōron), have aggressively attempted to rewrite Japan’s history of war and colonization and advocate a nationalism that abandons the selfishness of today’s youth and emulates the sacrifices of the kamikaze pilots.

2 Aaron Gerow, “Fantasies of War and Nation in Recent Japanese Cinema,” Japan Focus (20 February 2006)

3 Yoshikuni Igarashi, “Kamikaze Today: The Search for National Heroes in Contemporary Japan, ” in Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia, eds. Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007): 99-121.

4 Shūkan Kinyōbi (6 January 2006); or Julian Ryall, “Raising the Yamato,” Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan.

5 See, for instance, the rightwing blog: red.ap.teacup.com/sunvister

6 See E. Ann Kaplan, Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in Media and Literature (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2005); Joshua Hirsch, Afterimage: Film, Trauma, and the Holocaust (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004); or Janet Walker, Trauma Cinema: Documenting Incest and the Holocaust (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

7 See Nakamura Hideyuki, “Tokkōtai hyōshōron,” in Iwanami kōza: Ajia, Taiheiyō senno, vol. 5: Senjō no shosō (Iwanami Shoten: 2006): 301-330; and Nakamura Hideyuki, “Girei toshite no tokkō eiga: Otokotachi no Yamato/Yamato no baai,” Zen’ya 7 (Spring 2006): 134-137.

8 Hirsch 13.

9 “Onomichi fan kakutoku ni kōken,” Chūgoku shinbun, 8 May 2006.

10 Played by Nagashima Kazushige, son of baseball legend Nagashima Shigeo.

11 While there are doubts about the authenticity of this statement, it was popularized by Yoshida Mitsuru’s Requiem for Battleship Yamato. The same sentiment is uttered in Lorelei as well.

12 Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, “Melodrama, Postmodernism, and Japanese Cinema,” East West Film Journal 5.1 (1991): 28–55.

13 Always—Sunset on Third Street (Always—sanchōme no yūhi) was released in 2005 and Always—Sunset on Third Street 2 (Always—zoku sanchōme no yūhi) hit theaters in 2007. Both were based on the manga by Saigan Ryōhei and directed by Yamazaki Takashi. The first film was the seventh best-grossing Japanese film of 2005, and its sequel the third best of 2007.

14 The longer version of this essay considers other recent kamikaze films such as For Those We Love (Ore wa, kimi no tame ni koso shini ni iku, 2007) and Sea Without Exit (Deguchi no nai umi, 2006). Few such films have been made since 2008, but the rewriting of the postwar has continued with remakes of classic postwar films such as Kurosawa Akira’s Sanjuro (Tsubaki Sanjūrō) and Hidden Fortress (Kakushitoride no san akunin) or Kudō Eiichi’s Thirteen Assassins (Jūsannin no shikaku). It will be important to see whether the trauma of the March 11 disaster will be used as another means for avoiding the problems of the postwar—including the institutional structures that themselves led in part to the Fukushima accident.