Reflections on Korea in 2010: Trials and prospects for recovery of common sense in 2011

The original Korean text is available here.

Paik Nak-chung

It seems that Korean society experienced more trials than usual in the year 2010. Perhaps it feels that way because the final weeks since the shelling of Yeongpyeong Island on the West Sea of the Korean peninsula on November 23 have been filled with events that evoke grief, anger, and anxiety.

As for the Yeongpyeong incident itself, whatever its cause or justification, the fact that North Korea deliberately opened fire on South Korean territory is enough to bring shock and anger. To make matters worse, the incompetence and sloppiness of the South Korean government in its initial response caused uneasiness among the citizens, and its belated displays of toughness and escalation of tension, proclaiming “readiness for a full-scale war,” has added to South Korean people’s sense of insecurity and even stirred their anger.

The scene of the two major incidents near the contested Northern Limit Line 2010

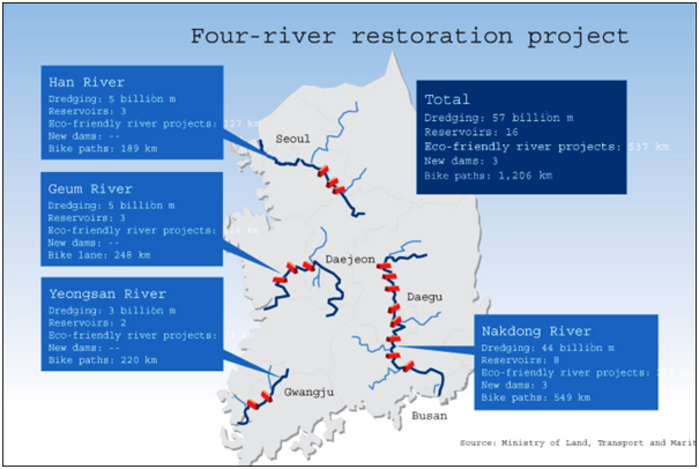

Taking advantage of the security crisis, members of the ruling Grand National Party (GNP) on December 8 unilaterally and employing physical force rammed through the National Assembly the annual budget and other disputed bills. Such action trampled upon the system of checks and balance and rule of the law, a fresh reminder of the crisis of democracy in Korea. The main reason behind this ‘snatching’ action apparently was to push on with the Four Great Rivers Project and to pass the related pernicious legislation known as the “Water-Friendly Region Law.”1 We may now foresee an accelerating destruction not only of the nation’s environment but of democracy and rule of law as well. In the meantime, the speedy economic recovery that the government boasts about, setting aside for the moment the view of some experts that we still have to wait and see how real the recovery is, has not succeeded in improving the livelihood of ordinary people or creating many new jobs. Indeed, even those with decent jobs feel overburdened with the cost of child care and privately paid informal education, and have gone on a “strike against child-bearing” to produce one of the lowest birth-rates in the world.

As for inter-Korean relations, President Lee Myung-bak himself virtually admitted the failure of his North Korean policy, “Denuclearization, Opening, 3000,”2 when in his address to the nation on November 29 he ruled out the possibility for North Korea to give up its nuclear program voluntarily. Is the only thing now left either war or living in a state of continued threat while waiting for regime collapse in Pyongyang?

The Cheonan incident as a turning point and its functional relation to the Yeongpyeong Island attack

It is clear that the antagonism that has built up between the two Koreas lies in the background of the attack on Yeongpyeong Island. Though with ups and downs, tension had persisted since the launching of the Lee Myung-bak administration, but what turned this into outright hostility was the incident involving the naval ship Cheonan last March.3 Thus, in order to have an accurate picture of today’s situation, we need to return to that turning point and calmly review what has transpired since. For an appropriate response is possible only on the basis of an accurate understanding of the situation.

After the attack on Yeongpyeong Island, popular sentiment attributing the sinking of the Cheonan to North Korea has gained strength in South Korea. It has also become easier to accuse anyone casting doubt on the JIG report of being ‘pro-North Korea and a Red’. However, the truth concerning the sinking of the Cheonan is something to be determined neither by popular sentiment nor political logic. It belongs to the realm of facts and can only be discerned through reason and logic.

Unfortunately, there is as yet no agreed conclusion regarding the Cheonan that has stood the test of reason and science. The JIG’s conclusions have not passed the examination of independent scientists, while outside experts with limited access to the relevant data have not been able to offer a convincing alternative explanation. Accordingly, there is no single correct answer on the functional relationship between the attack on Yeongpyeong Island and the Cheonan sinking. One can only attempt inferences starting from multiple hypotheses.

Let us consider just two such, for brevity’s sake. Hypothesis A: Despite all the faults and inconsistencies of the JIG report, the Cheonan was indeed sunk by North Korean attack. Hypothesis B: Even though the full truth is unknown, there at least was no attack by North Korea on the Cheonan.

What does Hypothesis A imply about the shelling on Yeongpyeong Island? First, if the North Korean military, which had attacked and sunk the Cheonan, then attacked Yeongpyeong Island, this truly is an intolerable provocation. Moreover, the same North Koreans who expressed such elation after killing two marines and burning down some civilian dwellings through their shelling vehemently denied responsibility for what must have been a far greater military feat, the sinking of a naval corvette and killing of 46 naval personnel in a move that still defies the calculation of military experts. Such behavior would throw doubt on the very mental stability, let alone peaceable intentions, of the perpetrating group.

Again, if Hypothesis A is correct, the response of the South Korean military proves not only incompetent but close to being criminal. The country had lost a naval ship and scores of innocent lives through the attack on the Cheonan, and the whole world, not to mention the entire nation, had been thrown into turmoil. But what are we to say of a military that (according to the testimony of the chief of National Intelligence Service to the Intelligence Committee of the National Assembly) had detected in August signs of preparation for an attack but remained totally unprepared, presuming this was just another bluff by the North? Not just the resignation of the Defense Minister (which did happen), but a massive reorganization of the top echelon of the military would be in order.

If, on the other hand, Hypothesis B is correct, the response by the South Korean military becomes somewhat more understandable. As at least key figures in the government and the top military leadership must have known that the Cheonan had not been attacked by the North, the intelligence gathered in August regarding a possible attack on the island could have sounded like yet another habitual threatening by the North. Of course, this does not excuse the grave error of judgment, nor absolve responsibility for the incompetence in responding to the actual attack. However, the utter disgrace of the entire South Korean military under Hypothesis A would at least be alleviated.

Concerning the North Korean regime, too, Hypothesis B enforces a considerably different view. The attack on South Korean soil remains a clear violation of the Armistice Agreement as well as the North-South Basic Agreement of 1992, and an indisputable provocation. But it becomes more probable that the attack was a meticulously calculated operation on Pyongyang’s part. At the time of the Cheonan sinking there was talk of a possible inter-Korean summit meeting. However, the incident changed at a stroke the whole inter-Korean relation to one of antagonism; North Korea faced with the danger of being branded as a criminal on the international stage and a series of unprecedented high-intensity military exercises by South Korean and American forces ensued. In this context North Korea may have decided on a deliberate gambit of its own. Nor would the outcome be considered a total loss. Of course, it is a serious loss to alienate the South Korean people, but such a long-term consideration was never a top priority in Pyongyang’s calculations. More important to them and a possible cause for celebration would be their success in clearly impressing on the international community the disputed status of the West Sea area, while strengthening their own internal unity. This would also create new opportunities for negotiations with the United States, aided by the restraint North Korea showed regarding new live-fire drills by South Korea as well as through reported agreements with New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson during his visit to Pyongyang.

A mapping of incidents involving North and South Korea, 1958-2010: The Guardian

Toward 2011 as a year to begin recovery of common sense and humane culture

Which of the two inferences seems more reasonable will be decided by each person, depending on his or her convictions and good sense. One should not forget, however, that these are no more than inferences deriving respectively from two mutually exclusive hypotheses, A and B, and which premise (or variant of the premise) is correct belongs wholly to the realm of empirical facts.

Not that we can entrust all matters to natural science. For instance, science alone will not tell us what to do once the truth has been ascertained, and dealing with a situation where scientific truth is being disregarded will also call for humane culture and competence beyond natural science. However, recognizing and respecting the authority of science in matters where science should have its say, while also doing what needs to be done beyond the boundaries of science, is precisely what constitutes humane culture and the necessary qualifications for democratic citizenship.

At any rate, whether the Cheonan was sunk by a torpedo attack, ran aground, hit a mine, or suffered a mine explosion after a grounding accident, is wholly a question that must be answered scientifically by recourse to physics, chemistry, etc. There can be no right or left, nor liberal or conservative, on the matter. Yet the fact that this question has been immersed in political and ideological battles has been one of the most painful frustrations of 2010. It also demonstrated the shallowness of our general culture not only among those in the government, the legislature and media but among intellectuals as well.

Fortunately, South Korea in 2010 was not totally dominated by lack of culture and common sense. A number of courageous individuals came forward attempting to expose the truth, at considerable personal risk, while numerous internet users and anonymous scientists responded and supported those efforts. More importantly, in the nationwide local elections of June 2, the people successfully resisted the so-called “North wind”4 deliberately instigated by the government, sending a stern message of warning to President Lee Myung-bak.

The most difficult challenge, however, probably will come when the truth about the sinking of the Cheonan has been brought to light. Whichever of the two hypotheses turns out to be correct, the situation is dire. While the proposition that war must be prevented will still hold true even if Hypothesis A is correct, it will be an unnerving task to manage an utterly dangerous situation in which a North Korean regime not only criminal but impervious to rational calculations possesses nuclear weapons as well . On the other hand, if in accordance with Hypothesis B there was no North Korean attack on the Cheonan, but our government has deliberately distorted and even fabricated the evidence, this too is a highly unnerving and dangerous state of affairs. We cannot exclude the possibility that in order to cover it up the government may resort to other extreme measures. And it would hardly be desirable to see a legitimately elected government falling into a state of paralysis. Only the combination of sound common sense on the part of ordinary citizens and the rational capabilities of various individuals in their respective fields, transcending the antiquated framework of liberal versus conservative, will overcome this crisis and realize a new leap toward the future.

|

Marine Corps C-130 Hercules leads a formation of F/A-18C Hornets, right, and A/V-8B Harriers as they fly in formation over the aircraft carrier USS George Washington in the seas east of the Korean peninsula summer 2010 (U.S. Navy) |

Korean society since its democratization in 1987 has enjoyed a space open to a change of political regime through the electoral process. Thus, any talk of a ‘new leap’ that fails to take account of the two major elections in 2012, for the National Assembly in April and the presidential election in December, will prove unrealistic. However, no great results in 2012 can be expected, either, unless recovery of common sense and humane culture, together with a wholesale refurbishing of the nation’s governance, can begin in 2011. Above all, we need to display wisdom in applying to the new political environment the lesson of the 2010 local elections regarding the value of coalition politics. Also, this process naturally must reflect the new forces, not necessarily related to electioneering, that have been maturing during the past year in various sectors of our society. The endeavors continuing in the religious and civic sectors against the Four Rivers Project have so far failed to alter government policies, but in certain ways they are changing the very fabric of our society. The struggles of the most disadvantaged workers for livelihood and jobs scored valuable victories at Giryung Electronics and at KTX.5 And these should not be judged by their scale alone.

Looking back, 2010 was a year of considerable achievements as well as frustrations and trials. Personally I am full of hope that, starting from those achievements and trials, we may go on in the coming year to make advances comparable to any year in our recent history.

Paik Nak-chung is Editor of the South Korean literary-intellectual journal, The Quarterly Changbi, and Professor Emeritus of English Literature, Seoul National University.

Translated by the author with the assistance of Beckhee Cho.

Recommended citation: Paik Nak-chung, Reflections on Korea in 2010: Trials and prospects for recovery of common sense in 2011, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 2 No 1, January 10, 2011.

Notes

1 The Four Great Rivers Project is a major civil engineering project being pursued by the Lee Myung-bak administration with the proclaimed aim of preventing flooding, solving water shortage problems, and improving the quality of drinking water of the four major rivers in South Korea. Despite broad public opposition including expressions of concern from local governments, opposition parties, academia, environmental groups and the four major religious orders that the project would wreak havoc with the nation’s natural environment while doing little to actually bring about the promised benefits, the government has pushed forward with unusual speed and showing little regard for procedural regulations. The “Water-Friendly Region Law” gives the Korea Water Resources Corporation extraordinary powers to develop leisure and tourist facilities in the vicinity of the four rivers. The opposition claims that this law is meant to compensate the Corporation for the huge debt incurred by undertaking the Four Rivers Project as the government’s proxy, a legally questionable move serving to exempt much of the Project funds from legislative scrutiny. (All notes provided by translator Beckhee Cho)

2 Lee Myung-bak’s campain slogan and subsequent policy “Denuclearization. Opening. 3000” promises to help North Korea reach a per capita GDP level of US$3,000 within ten years in return for giving up its nuclear program and opening its society to the outside world.

3 The South Korean navy corvette Cheonan split in two and sank on March 26, 2010 near Baeknyeong Island in the West Sea, killing 46 seamen. The Lee Myung-bak administration organized a joint military-civilian investigation group (JIG) to look into the cause of the sinking. The JIG announced in its ‘interim report’ on May 20 that the Cheonan had sunk as a result of a North Korean torpedo attack, a charge that Pyongyang denied. The Lee government took the case to the UN Security Council, calling for a UN resolution condemning North Korea. However, with China and Russia opposing it and independent scientists raising doubts about the JIG findings, the Council only agreed on an ambiguous presidential statement condemning the incident without specifying North Korea as the culprit.

4 The term signifies the influence on election results by negative developments in North-South relations. The governing party suffered a serious setback in the wake of the anti-North campaign waged by the government on the issue of the alleged torpedo attack.

5 The struggles of summarily discharged workers at Giryung Electronics for reinstatement and of the female train attendants of the high speed trains (Korea Train Express, or KTX) at KORAIL to gain regular employee status have ended in victory for those who had persisted through close to five years of strikes, demonstrations and legal battles.