A dialogue between Uradyn E. Bulag and Burensain Borjigin

This is the text of the 2019 “Nomad Relays” Academic Lecture

Nomad Relays is an annual non-profit event celebrating nomadic culture on a Saturday of every June. Initiated by film director Uragshaa (Wuershan), musician Yalagch (Ilchi), anthropologist Uradyn E. Bulag and artist Chyanga (Qin Ga) in June 2018, the event aims to bring academic lectures, art exhibitions, films, musical performances and other related activities together to present the charms of nomadic culture, explore its contemporary significance, and reflect on its inheritance and future development.

On 8 June 2019, in the second annual Nomad Relays event held at Mongol Camp (South Camp), Chaoyang District, Beijing, Burensain Borjigin, a renowned Mongolist historian based in Japan, was invited to lecture on the inner world of nomads and engage in a dialogue with Uradyn Bulag. In the lecture, Borjigin shared his educational and academic research experiences and his embarrassment at his own identity as a peasant Mongol. He vividly interpreted the problems of diversification in today’s Mongolian world caused by a variety of forces such as sedentarisation cum agriculturalisation, and marketisation cum urbanisation. In the dialogue, they further discussed significations of “diversity” for nomadic culture in different contexts. They also emphasised the importance of understanding nomads’ inner world in order to strengthen their confidence to communicate with the outside world. Below we present a lightly redacted English version of Borjigin’s lecture and the impromptu dialogue between Bulag and Borjigin.

|

|

Hello everyone!

First of all, I am very grateful for the invitation from the “Nomad Relays”. When I first heard the term “Nomad Relays”, or “Youmu Jihua” (Nomad Plan) in Chinese, last year, I wondered what the so-called “Plan” was. How different was the “Plan” from the “Naadam” where Mongols gather together for wrestling, horse racing, drinking and singing? I was curious. I never expected that I would be lucky enough to participate in this “plan” the following year. Many thanks to the “Nomad Relays” itself, and to the four organisers, who are innovators and pioneers, exploring new ideas to support and lead the future direction of the nomads. I personally think that, strictly speaking, there are no nomads in Inner Mongolia or in China today. However, the gathering of all of you here in Beijing demonstrates that nomadism is still vibrant. We can claim to be nomads today, or we can call ourselves “the descendants of nomads.” I am even more grateful to all the guests who are interested in the descendants of these “nomads”. I am very happy to be able to meet you all.

Knowing myself and accepting myself

First, let me introduce myself. I want to do this because the beginning of my academic experience and thinking began with knowing myself and accepting myself. This process is closely related to today’s topic, so let me do some detailed self-introduction.

In the early 1960s, I was born in a small village with 30 Mongolian families in Khüree banner, located in eastern Inner Mongolia. When I was born, this was a semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral area. I remembered that there were many flocks of sheep and goats, and herds of cattle and horses in our village when I was in elementary and middle school. Of course, they belonged to the Production Brigade. These herds of animals would spend the late autumn and winter in a desert 40 kilometres away from the village, which we call “Tobu“. In spring and summer, when the herds returned to the village, we could also eat some dairy products. Therefore, more precisely, I should say that I was a child of a semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral herding family in spring and summer, and a peasant’s child in winter.

Unfortunately, with the disintegration of the People’s Commune, the Production Brigade was disbanded in 1980. Those herds were assigned to individual households, and I have never seen proper herds of cattle, sheep or horses ever since. Since then, the homeland in my memory has become more like a farming village. Gradually, the so-called semi-pastoral elements in the semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral areas have drifted away. The proportion of agriculture has become larger and larger, and the village’s farming characteristics have grown stronger year by year. Therefore, even though I was born in a semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral area, I actually grew up in a farming village.

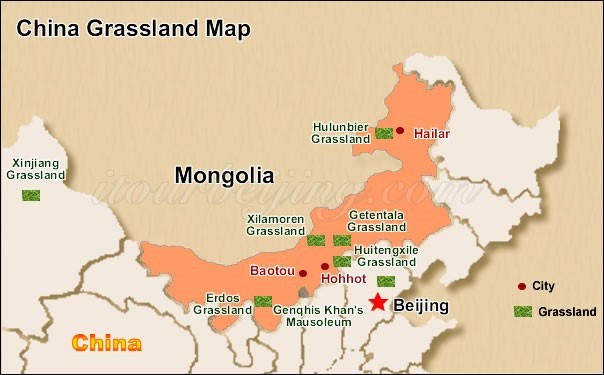

In 1980, the third year after the college entrance examination system was restored, I was admitted to Inner Mongolia University. 1980 was the beginning of China’s reform and opening up. It was a very extraordinary time. Frankly speaking, I was very fortunate to have grown up during this period. After graduating in 1984, I was assigned to the Inner Mongolia Radio Station as a journalist until I went to Japan to study in 1992. That is to say, after university graduation, in the extraordinary era of the early days of reform and opening, I travelled throughout Inner Mongolia and much of north China as a journalist. The history of our Mongolian people has been less than a thousand years since the time of Genghis Khan. In this historical process, the Mongols in China in the 1980s were the first among world Mongols to taste the market economy. From Ejine in the extreme west of Inner Mongolia to Hulunbuir in the easternmost part, I visited herdsmen in the depths of the grasslands and semi-herders living in the desert, trying to understand and report how they met the challenge of the wave of marketisation that had never been experienced before. Of course, we were then still in a more complicated state in which the “planned economy” and the “market economy” coexisted. In short, I had the privilege of doing journalism in Inner Mongolia during this extraordinary era in the mid to late 1980s.

I went to Japan for further study in April 1992. As China’s reform and opening up progressed in the 1990s, there was a wave of self-funded study abroad. I have lived and worked in Japanese for 27 years. This is a long time. I have lived in Japan for the same period of time as I lived in China, but I have spent most of my adult life in Japan. Interestingly, the years I lived in Japan have been a special period after the end of the nation’s bubble economy, which the Japanese call “the lost 20 years.” At the same time, these two decades have been a period of rapid economic growth in China, so my 20 odd years in Japan have seen China’s economic and social rise, while Japan has remained relatively quiet. I don’t quite agree with the statement that Japan has been going downhill for the past two decades, especially the view that Japanese society has stagnated. Instead, it is better to say that China has developed rapidly in these years.

I have been living in Japan feeling the gap and travelling between China and Japan. I feel sorry that I did not have the chance to personally experience the development of my homeland. Honestly, I’m sometimes envious of everyone living in China in such a vibrant era. Of course, I come back many times a year, hoping to keep up with the pace of development in China, but my flesh is weak. Today, I would like to talk about the question of nomadic tradition from the perspective of a Mongolian who lives and works abroad.

My first impression after I arrived in Japan was that Japan was one of the countries that liked Mongolian people and nomadic culture the most. When they heard that I am a Mongol, they were extremely excited, showing unreserved curiosity, saying “You must have ridden a horse to school”, “You must have grown up in a yurt”. The purpose of my stay in Japan was to pursue an academic career, and I believe an academic should be honest and tell the truth. So I told them: Although I am a Mongol, I did not go to school on horseback, nor was I born in a yurt. I was born in a mud house. I never had a chance to ride a horse when I was young. I rode donkeys for some time, if that counts. That greatly disappointed the Japanese; they did not want to recognise that I am a Mongol. At that time, I thought, “whether I am a Mongol or not, it is not up to you to decide”. I felt that the Japanese had a standard, equating Mongols with nomadic people. They were not willing to accept me as a Mongol, and any further explanation on my part was futile. Under this kind of psychological entanglement and struggle, I entered Japanese society step by step. I thought at that time: how did I become such a person who claimed to be Mongolian while others would not agree? My ancestors were originally nomads. They also lived in yurts. They rode fast horses on the vast grassland. How did I become a peasant later? I was determined to figure out how I became a peasant. Otherwise, I couldn’t accept myself, let alone others. How could I conduct research while I didn’t even know who I was, and how I turned into such a person today? In this psychological entanglement I began to think. My Japanese friends around me, including my supervisor, were all confused about my peasant Mongolian background; I seemed to have shown them a Mongolian identity which was not quite the same as they had imagined. I used to wonder, even worry, about how to become a “decent Mongol”. I began to think about how the nomads of the past became peasants today, and in such large numbers. It was so hard to express my cultural trauma: how can a person who grew up riding a donkey dare to say that he is a real Mongol?

|

Although I haven’t been riding a horse, I have to keep up appearances. In order to “make things up”, in the summer of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, I rode a horse from the West Ujumchin grassland to the Dushikou Gate of the Great Wall (in Chicheng county) to the north of Beijing. I rode for 10 days and covered more than 700 kilometres, trying my best to feel what it was like to be a Mongol. I also tried to feel the greatness of our ancestor Chinggis Khan and his army’s military expedition on horseback hundreds of years ago. In the following summer (2009), I again tried to ride from West Ujumchin to Hohhot, but had to return after travelling for more than 500 kilometres due to drought. Thus, I spent two summers riding through the central part of Inner Mongolia, making the experience a “compensation” for my growing up riding a donkey! The greater gain was a three-dimensional experience I obtained of the historical process of the Mongols.

There is a stereotype in the international community: the Mongols are nomads and a horse-riding people. Apparently, the world is not willing to acknowledge our changes. In my academic journey, frankly speaking, the term “nomad” is a kind of burden. It does not like a peasant child like me, but it does not give up on me, either. On my part, I like it but I can’t be completely accepted by it, and it is difficult to be freed from it. This is a very complicated relationship. How to confront “nomad” and then go beyond oneself? This is also my academic motivation. I have always had both troubles and motivations, and it has prompted me to make further explorations. Therefore, my self-recognition process is my academic journey, a journey also to understand the diversity of the Mongolian world. To make an additional point, Japan is a place not far away for understanding China, understanding Inner Mongolia, and understanding the Mongolian world; it takes just three hours to reach an international stage from where one can think about the Mongolian world independently.

How to understand the diversity of the Mongolian world?

Looking back at history, since the end of the 19th century, Inner Mongolia has been inundated by immigrants from inland China. Because of the massive land reclamation, the entire grassland in the south shrank in waves. The number of times the herdsmen move throughout the year decreased gradually, and they were forced to settle down when there was no space for moving. After settling down, since they could not make a living by raising livestock, they began to grow crops. Also low yield of crops in arid areas led to the enlargement of cultivated land so that pastures became smaller and smaller, gradually resulting in semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral areas. In the end, there were no pastures for even raising a few cattle or horses, and the only recourse was farming.

Great changes have taken place in the short period since the end of the 19th century. From the Tumed Plain at the foot of the Yinshan Mountains to the Harchin–Eastern Tumed area, the Shiramörön River and the Nonni River basins, cultivated land is everywhere. Most Mongols in the eastern region have been farming for less than a hundred years. Strictly speaking, the eastern Mongolian banners in the 1930s and 1940s still retained a very strong pastoral culture. The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region has a total area of 1.18 million square kilometres, in which a vast Mongolian farming village society has formed on the land of 210,000 square kilometres to the southeast of the Great Hingan Mountains. I call these settled farming communities in the southeastern part of the Great Hingan Mountains “Mongolian farming village society”. This conception is what I have always used in research, and it seems to have become a conventional statement in the academic world. Nearly 3 million Mongolians live in a small space of less than 210,000 square kilometres, and the population density is probably second only to that of Ulaanbaatar. For example, nearly 400,000 of the 540,000 people in the Horchin Left-wing Middle Banner are Mongols. In our history, rural Mongols have never lived so crowded together.

In the 20th century, we experienced another wave of modernisation. How did modernisation come about? Of course, it came from the theory of social evolution, the application of the principle of “the Law of the Jungle” from Darwin’s theory of evolution in the process of social development. In such a fierce competition, the Mongols were obviously a vulnerable group struggling to survive. At the beginning of the twentieth century, with the wave of modernisation and the socialism that followed, our most precious nomadic culture became the target for elimination. Nomadism was considered to be a backward mode of production, so we were compelled to seize the opportunity to settle down. In other words, nomadism, the most treasured part of the Mongolian culture was rendered “waste” to be discarded. Settlement has become an irresistible hard mission imposed on the Mongols since the twentieth century.

China launched reform and opening in 1978, and last year (2018) happened to be the 40th anniversary of reform. This was an extraordinary period of 40 years. Mongolia has entered democratisation and marketisation since 1990. In other words, since the 1980s, Mongols living in Central Asia and North Asia have met with an even more severe test. The pastoral economy has faced the impact of the market economy, the nomadic culture has entered the market, and the Mongols everywhere have begun to urbanise. In this dramatic change, we have lost the most precious nomadic tradition.

However, having said this, our history and traditions are great and they are not out of reach. The “Nomad Relays” like today has brought together Mongolian people from all walks of life to meet each other and accept each other. Instead of blaming or questioning whether we are real Mongols and who we are, this event has provided a good opportunity for us to accept and embrace each other.

“Fantasised singularity” and “diversity of reality”

In the past, our traditions and honours came from tolerance and diversity. The cosmopolitan nature of the Mongol Empire was predicated on its tolerance for people of different cultures and beliefs and on the accommodation of multiculturalism. The Mongol Empire was a diverse world. It can be said that one of the important factors that enabled the Mongol Empire to become a great world empire was its diversity. This greatness came precisely from the openness and tolerance of the nomads themselves. The problem is that there is a difference between the tolerance of the strong and the tolerance of the weak. The Mongols at the height of the Mongol empire were militarily the most powerful people in the world, and their tolerance came from their self-confidence and power. But today, do we have the confidence for tolerance? There is also a fundamental difference between the diversity of the Mongol Empire and the diversity of today. What do people like in us? Our unconstrained nature, open-mindedness, or informality? However, we Mongols seem to be pursuing what may be called singular nomadism. Using nomadism as a standard for being Mongolian, if someone does not meet the standard, they begin to feel inferior or mutually exclusive. People like our tolerant attitude, but our heart yearns for another very different self. Where did this disparity come from? I believe that the nomadic singularity we are pursuing now is a fantasy world, and the reality before us is diversity. That is to say, there is a sharp gap between the “fantasised singularity” and the “diversity of reality”.

A song popular both in Inner Mongolia and in Mongolia sings “bi malchin hün, bi jinhene Mongol hün“, which means “I am a herder, so I am a real Mongol.” It can be seen that people are fighting for who is a real Mongol. Mongolia has nearly three million people, and there are more than six million Mongols in China. It is not much together, but the debate about authenticity is endless. If you want to prove that you are a real Mongol, you can go back to the countryside to look after animals. However, most Mongols seem reluctant and they have all rushed to the city. So, everyone is arguing about a problem that doesn’t make much sense. This “nomadic singularity” not only becomes the conceptual boundary with the other, that is, exclusivity, but also constitutes the violent exclusivity of the internal world. This is my biggest concern. It is like a double-edged sword, which is a very delicate matter.

The mental infighting of our Mongols is serious. Where does this spiritual internal friction come from? In less than a thousand years of history, the Mongols have transformed themselves from a strong confident people proactively embracing diversity to one that experiences diversity in a passive way, thanks to the arrival of immigrants and the change of lifestyle in the late Qing Dynasty. Later, we started fantasising about “nomadic singularity”. Now nomadic culture has become a spectre for us, visible, but untouchable. The diversity of the Mongol Empire brought glory and the vast world to the Mongols at that time, while today’s diversity has brought us nothing but crisis, threatening the remaining self-identity of the Mongols. The history of the Mongols, brilliant but heavy, has become an unbearable weight almost crushing our weak Mongol consciousness today. Mongol history is too great for us to abandon, but we are frightened of the prospect that we might lose it one day, for this legacy is also too big and too heavy.

Today the word “nomad” has become the only key word or point for our connection with a glorious history. Afraid of losing this link, today we refuse to change and refuse to recognise our non-nomadic elements. Like me, if someone says that I am not a nomad, I feel frightened, not knowing what to do for not being a “nomad”. It has even bothered me to a point where I dare not say: “I’m a Mongol”, still less that I am a descendant of Chinggis Khan. Even though my family name is Borjigin – the royal family – I can’t say that I am a descendant of Chinggis Khan because I am a peasant. In the twentieth century, we developed a contradictory attitude towards nomadic tradition, that is, experiencing pride and crisis simultaneously.

Here is an example. In the first half of the twentieth century, there was a representative figure called Lubsanchoidan, an intellectual from the Harchin Left Banner. In 1907 he went to Tokyo University of Foreign Studies as a Mongolian language teacher. We can imagine that although the Japanese like Mongolians, if it was today, they would never have set up a Mongolian language major in a national university such as Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. However, after the Russo-Japanese War (1905), Japan attached great importance to the Mongolian region, and established a Mongolian language major at the Tokyo Foreign Languages School (the predecessor of Tokyo University of Foreign Studies). Lubsanchoidan was the first overseas Mongolian teacher who was invited to the school. He lived in Japan for four years and discovered two things: First he discovered the greatness of the Mongol Empire and Chinggis Khan. At that time, Japan was expanding to Asian countries, and they were very interested in the Mongol Empire. And Lubsanchoidan, who almost had lost confidence in Mongolian society, re-recognised the greatness of his ancestors during his time in Japan. At the same time, he encountered another terrible problem in Japan, that is, social evolution. He was shocked to see modern architecture, railways and factories in Tokyo and Yokohama.

Looking back at the Mongols, there was a world of difference. At that time, it was an era of imperialism and the theory of evolution was fierce. He felt that the Mongols faced a crisis of being eliminated. So, Lubsanchoidan found both the greatness of his ancestors and the crisis faced by the Mongols at that time. It can be said that his famous book Mongolian Customs was a work written out of a sense of crisis. After he returned to China, he wrote a lot about what he had seen and heard in Japan and published it at a printing company created by Temegtu in Beijing. Lubsanchoidan believed that the root cause of the infirmity of the Mongols today was that they had been in a nomadic state for a long time. Moreover, he also saw that nomadism had ceased to exist in his homeland Harchin, and it had evolved into a farming society. The Harchin area had lost its nomadic industry as early as the Jiaqing era (1796-1820). Therefore, his discovery of the three very different facts about the history and the present state of the Mongols during his stay in Japan troubled and overwhelmed him.

In the second half of the twentieth century, Mongols in Central Asia and North Asia were baptised into socialism, another wave of modernisation. Fear of change was also prevalent during this period, and this fear came from the segregationist policy of the Qing Dynasty, which had confined Mongols in their banners. If you wanted to buy something, you had to wait for Chinese traders to come to your doorstep. It is usually the case that isolation deprives people of any contrast with the outside world, thereby making them lose the mechanism for progress. People’s communication with others is to measure and examine themselves through comparing with others and finding their own strengths and weaknesses. The segregationist policy of the Qing Dynasty made us very introverted and we could only praise the glory and greatness of the past. In a passive state of mind, once you change, you are worried about losing yourself. But everything in the world is changing and it cannot be resisted.

Today our mission is to turn the negative mentality of resistance into a positive mentality of challenge. What is the nomadic spirit in the era of marketisation? In the era of marketisation, we have in fact seen hope in that our nomadic culture has begun to be consumed and is considered a meaningful resource. That we have gathered here today in a yurt at the centre of Beijing, the capital of a big country with a population of 1.3 billion, is itself a demonstration that we have new hopes and opportunities. The more highly marketised and urbanised, the more people become nostalgic about nature and the cyclical lifestyle, and our nomadism is likewise increasingly romanticised.

Thank you very much!

|

A Dialogue between Uradyn Bulag and Burensain Borjigin |

Uradyn Bulag

Professor Borjigin’s lecture is very easy to follow, but it has struck our heart. From your speech, what can we learn? When we inspect the inner world of nomads, we perceive agony. Indeed, the starting point of your discussion was precisely your own agony. I wonder where this feeling came from.

In my opinion, we have probably experienced two types of agony. One stems from homogeneity. In the Qing Dynasty, Mongols on the whole had become very pure because borders had been imposed between ethnic groups, with the Mongols being segregated from the Manchus, Han Chinese, Tibetans and other groups. Exchanges between different ethnic groups were forbidden. Therefore, each ethnic group was able to keep its own traditions and customs, maintaining its homogeneity. For two to three centuries during the Qing, Mongols were not allowed to study Chinese language, and were isolated from the outside world. If you were interested in the outside world or longed to see that world, you would be punished. In this way, Mongols had maintained their “purity”. However, as soon as this isolated world began to crumble at the end of the Qing empire, the Mongols immediately experienced a sense of agony as they felt their culture was being “polluted”.

On the other hand, our agony may have come from failure to meet Stalin’s definition of a nation as “a historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture.” If we examine ourselves by this standard, we realise that our “nation” or our “minzu” doesn’t satisfy any of these criteria. Many of our people don’t speak Mongolian language anymore. You (Borjigin) are a peasant Mongol, and although I was born into a nomadic culture, I’m no longer a nomad. When everyone recognises us as nomads, yet we can’t live up to the great nomadic traditions to meet their expectation, we are bound to feel agony.

So, from my perspective, our agony exists mostly on these two levels. Now the question is whether or not agony is a necessary evil. Do we want to put an end to agony or should we keep some of the pain? Putting it in another way, do we want to pursue a type of absolute happiness or do we need a certain degree of pain? I would love to hear your insight.

Burensain Borjigin

Concerning agony, here are my thoughts. During the Qing dynasty, or by the end of the Qing dynasty, the Mongolian people were basically nomadic, to different degrees. People nowadays, who have trouble with a variety of life choices, tend to believe that the nomadic society during that time must have been free of emotional pain. But the truth is that agony did exist, because we were unable to see the outside world, unlike the type of agony we experience today. When people couldn’t see the outside world, they lost track of time and space. In fact, they lived in a world that was gradually changing, but they did not notice the change, and they could not control it, which means they lived in a passively changing state. The most dangerous thing about passive changes is that people can lose their identity and become “polluted” without even noticing it. All the troubles were caused by isolation. However, I believe a sense of agony is necessary. Agony can lead to self-discovery, self-recognition, and eventually self-acceptance. If an ethnic group fails to accept who they are, it is very difficult for them to take the first steps towards the outside world. That is my view. Agony is necessary because it is the norm.

I want to add another point. The Mongolian community changed fast and dramatically between the early 1920s and the 1950s. Chinese society has also gone through dramatic changes since the 1990s. Many people tend to lose their direction at a time of extraordinary and rapid changes. They might not understand what they have experienced or know what to become. In a way, we have not had the time to objectively analyse and summarise the uncommon experiences of the Mongols in the first half of the 20th century. And yet, we face a similar problem today. When we have to change passively, it is very difficult for us to catch up with the times as well as to figure out the past, the present and the future. I believe we need to calmly re-organise our understanding of the history of the past few decades. During the two to three centuries of the Qing dynasty, we did not change much. In those slow and carefree years, Mongolian people lost their curiosity towards the outside world. Nowadays, major societal changes have made people lose their direction. Therefore, the process of understanding oneself must be accompanied by a sense of agony, which will likely continue in the future.

Bulag

I remember our first meeting over ten years ago and we have been joking about it ever since. I claimed that I was a descendent of nomads, but you were not.

Most people know that Inner Mongolia is divided into eastern and western parts. The eastern community is mostly agriculturally based whereas the western part has maintained some nomadic traditions. These traditions have filled western (Inner) Mongolian people with a strong sense of pride, especially in front of their eastern counterparts. However, I felt frustrated while doing research in Mongolia (The Mongolian People’s Republic) at the time. Initially, I was pretty proud (compared to eastern Inner Mongols), but when I went to Mongolia, people there thought nothing of me. In their eyes, Inner Mongols were all the same. There was no difference between the east and the west. I felt humiliated and was driven to write a book on the topic. The book is Nationalism and Hybridity in Mongolia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998). When I told you about this book, you were very happy. You were happy to learn about my frustration, weren’t you?! Anyway, I mean to ask: can we seek mutual understanding despite all the disagreements and conflicts? We have internal differences, but from what angle should we interpret the differences? In my view, our internal conflicts are historical, and it is actually an issue of authenticity – ‘Who is the true Mongol?’ Nevertheless, looked at from the outside, we are all the same, simply one type of people. At this point, how do we look at the diversity inside our culture?

Borjigin

When Professor Bulag and I visited Ulaanbaatar, I witnessed people calling him by the offensive name ‘hujia’ (Chinaman). I was “thrilled” about this for whatever reason! While we were in Inner Mongolia, you called me a ‘farmer’. Now we were in Mongolia, and people there did not see you as a ‘Mongolian’. For some reason, I felt we had at last become ‘equal’. This is of course a taboo topic for the Mongols, but the fact that we are able to discuss it today shows that “equality” between us has improved. Both of us live and work abroad, which gives us more opportunities to objectively discuss the problems between our subgroups. When we observe the entirety of Inner Mongolia from the outside, we often wonder – why do issues such as “the problem of the east and the west” exist at all in Inner Mongolia? Why do we have such a strong sense of mutual exclusivity? I believe we still have not been freed from the mentality developed as a result of the banner divisions imposed by the Qing dynasty. Banners were exclusive to each other, because each banner had its own jasaγ (hereditary ruler) and pasture. Therefore it operated on its own. For example, normally, I would never go to Ordos where you are from. I would not care about the way you live. We have never formed a system of mutual recognition. Admittedly, we live in a high-tech world now where we do work on computers and play with smart phones every day. But on the psychological level, we still hold on to old beliefs, which is a fact we tend to overlook. Therefore, within our culture there has always been this meaningless argument about authenticity. Besides, Inner Mongolia is a province-level region known in China for its pastoral economy. Who can represent that economy in Inner Mongolia? Of course, herdsmen are the rightful representatives. From a cultural perspective, I think agricultural Mongols probably have never wanted to represent Inner Mongolia. As a matter of fact, no one has ever told us how to develop our self-identity; it is just that we have never been able to overcome our internal differences. It still might take a long time.

Bulag

Now it’s very interesting that you brought up the concept of cultural representation. My perspective is slightly different. On the one hand, pastoral culture and pastoralist Mongols are known to be more representative of Inner Mongolia. But it is not an achievement we (pastoralists) have scored through struggle; this honour came to us not because we are powerful, but because of a different kind of imagination.

Let me try to look at it from a historical angle. Many vanguard revolutionaries and intellectuals in modern Inner Mongolia are agricultural Mongols. Take the Tumed Mongols for example. They don’t speak Mongolian. Another instance is the Harchin Mongols. Most of them don’t understand the language, either. Modern intellectuals from these communities pondered the fate of the Mongolian nation and the revival of its culture, and they actually began to imagine what Mongolian people should be like. These intellectuals worked very hard, and became modern revolutionaries as well as leading thinkers of the nation. They earned a lot of political capital. Compared to pastoralist Mongols in western and central Inner Mongolia and Hulunbuir, they occupied key positions in the government and the Party. With their political capital, they started to sort out and re-organise nomadic culture largely based on their imagination since they had greater discursive power. As a result, nomadic culture in Inner Mongolia today was rewritten mostly by agricultural Mongols instead of by real nomadic people.

Borjigin

I think there are many reasons for this. One of the main reasons lies with the Mongols in western and central Inner Mongolia who have maintained some degree of nomadic culture. They would love to go back to the old nomadic lifestyle if they had a choice. But the Harchin intellectuals had realised long ago that the heyday of traditional nomadic society had already passed. They were like the nomadic Arabs in oil-rich countries. Prior to the 1950s, most people in these Arab countries were nomadic, and now they have become citizens of rich nations. Today at the time when the whole world is worried about the depletion of fossil fuels, I imagine that they don’t fantasise returning to the nomadic age anymore. They know that the era has passed. When Inner Mongolian intellectuals in agricultural areas realised that there was no going back, they resolutely decided to turn nomadic traditions into a symbol to represent the national spirit in this brave new and diverse world. Pastoralist groups that maintain a certain nomadic heritage still dream of returning to the past. They struggle over the small size of their pasture every day: they used to move five times a year, but now they can move no more than twice or even can’t move at all. On the other hand, in arid areas, small and narrow pastures cannot be turned into farm lands. Survival is a serious matter that requires rational assessment and wise choices. It is not a matter of like or dislike.

Bulag

When we discuss the inner problems of our culture, we have two different perspectives – rational and emotional. Intellectuals tend to adopt the rational perspective, as you say. But to what extent have they really been rational?

Let me put it in a different way: We have seen a structural problem, namely, the internal structure of the Mongols is so complicated that they cannot communicate with each other any more. So the question is: when we think about this issue, should we take it as an internal problem, a matter for discussion only amongst us? Or should we work with outsiders to explore whether nomadic culture can be a common resource for all of us?

Borjigin

I think there are two aspects. On the one hand, descendants of nomads discuss nomadic culture in order to regain self-recognition and build confidence. In a way, we want to inject nomadic elements into our spirit. Our culture has been changed “beyond recognition”. We need to find a root, and build strong self-confidence. On the other hand, outsiders or foreigners love nomadic elements, their intention being to enrich their inner world, because they feel that nomadic elements have a strong culture of tolerance. Besides, since descendants of nomads in modern society are fragile, and we haven’t even managed to establish ourselves, outsiders have easy access to us. In this case, when a strong power loves you to enrich itself, we, as a weak power, cannot directly resist it. Because if we do, we will look less likeable. In the modern, globalised world, it’s unavoidable that different cultures interact and influence each other. If we successfully build self-recognition and rationally inject the nomadic elements into the depths of our soul, we shouldn’t be afraid of “love” from outsiders. Then we can turn the “love” of others into a power to serve us. But before that happens, we are still fragile. We’re worried that people will take away what we like before it becomes part of our soul. It will take a long time to build self-recognition in a rational way. I appreciate that the “Nomadic Relays” project is one of the tangible actions to develop such self-recognition.

Bulag

You brought up a key issue about being active or passive. From the historical point of view, nomads were considered to be active during the Mongol Empire. They actively embraced the world. For this reason, nomadic culture was considered to be tolerant of different cultures. Today, the homeland of the nomads has been knocked open, their world has been opened up, and they have been forced to accept the outside world. I wonder, however, to what extent nomads were really confident during the active phase. They might be very confident when they were conquering the rest of the world, but they didn’t necessarily know what they really wanted. At a certain point, they must ponder these issues including who they were, how to maintain their identity in the vast empire, and how to maintain their superiority over the rest of the world. To some extent, the process of embracing the world could involve losing their own identity. At this point, the nomads began to lose confidence. To stay true to their identity, they chose to retreat. Retreat was caused by the resistance of the outside world, but it was also a manifestation of their own giving up of any effort to sustain their empire. This is my personal interpretation, perhaps an anthropological point of view. You are a historian. What do you think?

Borjigin

I have a different interpretation. One of the reasons why Mongolian people have survived until today is that they were able to retreat, and they could do so because they were nomads. The Mongol Empire ruled China proper for over a century. When circumstances turned bad, they were able to run back to the Mongolian steppe because they had not been completely adjusted to the sedentary lifestyle. When they were in inland China, they managed to maintain their identity. Therefore, they could run away at the critical moment. The year 1368 (the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty) was a setback for them, but they survived because they had maintained their identity. Later, during the chaotic era of the Northern Yuan (1368-1635), they also ran away when the odds were against them. Why not if you don’t hold much chance of winning? Although running away was humiliating for Mongols in decline, it was actually a strength that allowed them to survive. The biggest problem we Mongolian people are faced with today seems to be the loss of this strength. We are no longer ‘able to take things and let them go easily’ as before. Admittedly, we live in a different era. We face different circumstances. How do we put our “natural talent” to use under these circumstances? We have not been exposed to market economy for long; thus, we face a new challenge in this fast-developing environment. Can we become flexible again when we need to? In order to adapt to the changing environment and survive, we must incorporate this gene of ‘being able to take things and let them go easily’ into the Mongols’ mental world.

Bulag

I’m afraid that I haven’t studied this gene you mentioned. But I do believe, regardless of what era or environment we live in, we must maintain our identity, that is, stay true to ourselves. You brought up the topic of singularity and diversity in your speech. If I understood you correctly, you were saying that we (researchers) tend to emphasise diversity as an essential aspect of nomadic culture but nomads stress nomadic singularity, that is, they think of themselves as true nomads and they exclude others. I should say, however, your singularity and diversity conception follows a binary logic. I would like to re-organise it from a different angle. Here are some of my thoughts. Building on the German sociologist Georg Simmel’s social geometry, we can categorise human society into three types by using numbers. A unitary society is formed by one person, its ultimate goal being to meld all people into one. But in reality, our modern society is largely organised along the democratic principle in which the majority have rights and are able to cast away or marginalise the minority by voting. That is a binary or dyadic society, formed by two people. If you add one more member, that becomes a triadic society. What does a triadic society look like? It is a society in which the weak is not always weak. They can form an alliance with other weak people to fight against the strong. A triadic society is a fluid society in which people can play games. A unitary society is still and unreachable, but people want to pursue it. A binary society is very tragic because in it the minority is always inferior to the majority, thereby forming a stable structure. Can we turn your diversity into a triadic or triangular society so that we can turn the tragic circumstance you described into a happy one to provide a possibility for minority nomads to survive?

Borjigin

Allow me to introduce the third monograph written by Professor Bulag: Collaborative Nationalism: The Politics of Friendship on China’s Mongolian Frontier (2010). It talks about a collaborative gaming theory. He put forward the anthropological theory of “triangularity” of nationalism for the first time. What he just said derives from that book. You’ll understand it better when you read the famous book which won the International Convention of Asia Scholars Book Prize in the category of Social Sciences in 2011. Now coming back to his question. In retrospect, I did treat ‘singularity’ as an unfortunate phenomenon in my presentation. Looking at singularity vs. diversity, I believe that “singularity” is the core. Why do we strongly hold onto the nomadic heritage? Because that is our core and we must accept it. The reason is that currently diversity works to our disadvantage. We are too fragile. If we are not careful, before we find our core, diversity will leave us with nothing. During the Mongol Empire, “singularity” and “diversity” were both easy to control and the Mongols used it to their benefit. But today we don’t have power to balance “singularity” and “diversity”. I understand that it may be necessary to stress this “singularity”. However, immature people are always volatile, they are either too happy or too sad. They can’t find a balance. Therefore, we need a rational process; even when we are not happy, we must still keep calm.

Bulag

So, could I interpret this to mean that we (Mongolian people) can’t afford to play the game yet; we need to build our strength, and then come back to play, right? I have one last question. Our internal world has many problems, and we have also gained experience and learned lessons. Do other nomadic people have similar agony? How do they cope with it? Could we possibly inspire them? Or what lessons can we learn from their experiences? What are the similarities and differences between different nomadic groups in the world?

Borjigin

I have found some comparable examples. There is a dry arid area that starts from North Africa and stretches across Europe and Asia. We call it “the Afro-Eurasian Dry Zone”. This is the cradle of pastoral cultures. There are two types of pastoral cultures: one is “Grassland Pastoral Culture” in the dry steppes of Inner and North Asia; the other is “Desert Pastoral Culture” in the Arab region. The former stretches from Kazakhstan eastwards. The nomadic peoples and countries of Central Asia, such as Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, have experienced a history similar to that of the Mongols. Apart from religion, our pastoral methods are basically the same. We have all experienced modernisation and socialism. However, the Arab “Desert Pastoral Culture” developed differently from us historically. Countries like Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia became wealthy after World War II because of their oil resources. By the 1960s, they had become very rich. Nowadays, they are very happy about “showing off” the culture of their nomadic era. For example, Kuwaitis are proud of their falcon culture, but I think few people in Kuwait are willing to return to “the era of falcons”. The Saudi Arabians have camel racing. They also reinterpret their traditional culture from a modern viewpoint. I don’t know if the Arabs have a sense of reality regarding crisis. For example, how will we live if oil is depleted someday? Will we return to the nomadic era? The evolution of the Arabs’ nomadic tradition is irreversible. There is no return, no matter what happens. Arabs treat their traditions differently from us. The descendants of Central and North Asian nomads seem to be more stubborn. They want to go back to the past if possible. However, when the descendants of nomads realise that the nomadic lifestyle is gone forever, we may have more courage to view our culture as soft power, and use it in our future lives. We can understand this situation from the way Arabs treat their nomadic culture.