Preface by Brian Victoria

In Part I of this series on D.T. Suzuki’s relationship with the Nazis, (Brian Daizen Victoria, D.T. Suzuki, Zen and the Nazis readers were promised a second part focusing primarily on Suzuki’s relationship with one of wartime Japan’s most influential Nazis, Count Karlfried Dürckheim (1896 –1988).

However, in the course of writing Part II, I quickly realized that the reader would benefit greatly were it possible to present more than simply Dürckheim’s story in wartime Japan. That is to say, I recognized the importance, actually the necessity, of introducing Dürckheim’s earlier history in Germany and the events that led to his arrival in Japan, not once but twice.

At this point that I had the truly good fortune to come in contact with Professor Karl Baier of the University of Vienna, a specialist in the history of modern Asian-influenced spirituality in Europe and the United States. Prof. Baier graciously agreed to collaborate with me in presenting a picture of Dürckheim within a wartime German political, cultural, and, most importantly, religious context. Although now deceased, Dürckheim continues to command a loyal following among both his disciples and many others whose lives were touched by his voluminous postwar writings. In this respect, his legacy parallels that of D.T. Suzuki.

The final result is that what was originally planned as a two-part article has now become a three-part series. Part II of this series, written by Prof. Baier, focuses on Dürckheim in Germany, including his writings about Japan and Zen. An added bonus is that the reader will also be introduced to an important dimension of Nazi “spirituality.” Part Three will continue the story at the point Dürckheim arrives in Japan for the first time in mid-1938. It features Dürckheim’s relationship with D.T. Suzuki but examines his relationship with other Zen-related figures like Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel as well.

Note that the purpose of this series is not to dismiss or denigrate either the postwar activities or writings of any of the Zen-related figures. Nevertheless, at a time when hagiographies of all of these men abound, the authors believe readers deserve to have an accurate picture of their wartime activities and thought based on what is now known. I am deeply grateful to Prof. Baier for having joined me in this effort. BDV

Introduction

Japan, the “yellow fist”, as he called the nation in “Mein Kampf”, caused Adolf Hitler a considerable headache. In his racist foreign policy he distrusted the Asians in general and would have preferred to increase European world supremacy by collaborating with the English Nordic race. On the other hand, he had been impressed as a youth by Japan’s military power when he observed Japan beat the Slavic empire in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. He also admired Japan for never having been infiltrated by the Jews. In “Mein Kampf” his ambiguous attitude let him place Japan as a culture-supporting nation somewhere halfway between the culture-creating Aryans and the culture-destroying Jews.1 He hoped that in the near future Japan and the whole of East Asia would be aryanised by Western culture and science and sooner or later the political domination of the Aryans in Asia would follow.

|

Fig. 1 Dürckheim country estate Steingaden as seen today |

As the brotherhood in arms with England turned out to be a pipe-dream, Hitler had to make a pact with the Far Eastern country. This allowed a group of japanophile Nazis to raise their voices and disseminate a more detailed and positive view of Japan. They were interested in Japanese religion and especially sympathized with Zen Buddhism.

The following article can be seen as a case study. Taking the intellectual and religious biography of Count Dürckheim as an example, the author investigates the question of how dedicated Nazis could connect their worldview to a kind of mystical spirituality and develop a positive attitude towards Zen.

Karl Friedrich Alfred Heinrich Ferdinand Maria Graf Eckbrecht von Dürckheim-Montmartin (1896-1988), today widely known as Karlfried Graf (Count) Dürckheim, was born in Munich, Bavaria as the eldest son of an old aristocratic family. Baptized Catholic, he was religiously educated by his Protestant mother, grew up at the family’s country estate in the Bavarian village of Steingaden, at the Basenheim Castle near Koblenz and in Weimar, where his family owned a villa built by the famous architect Henry van de Velde.

|

Fig. 2 Villa Dürckheim in Weimar |

In 1914, immediately after receiving his high school diploma, the 18-year-old Karlfried volunteered in the Royal Bavarian Infantry Lifeguard Regiment to serve on the frontlines for around 47 months as officer, company commander and adjutant.2 He never forgot the enthusiastic community spirit that filled his heart and the hearts of his fellow Germans at the beginning of the war. “I heard the Emperor saying, ‘I do not know parties any more, I only know Germans’. It remains in all our memories, these words of the Emperor, in those days at the beginning of the war.”3 Later he would say that during this period the meaning of his life had been the “unquestionable, ready-to-die-commitment to the fatherland.”4

Regularly exposed to deadly threats, the young frontline officer was intensively confronted with his fear but also experienced moments of transcendence.

There exists a ‘pleasure’ of deliberately thrusting oneself into deadly danger. This I experienced when embarking upon a nightly assault on a wooded hill, when running through a barrage at the storming of Mount Kemmel in Flanders, when jumping through a defile under machine gun fire. It is as if at the moment of the possible and in advance accepted destruction one would feel the indestructible. In all of these experiences another dimension emerges while one transcends the limits of ordinary life – not as a doctrine, but as liberating experience.5

This kind of “warrior mysticism” – a combination of military drill and blind obedience, fight to the very end, a devotion to and melding with the greater whole of the fatherland that culminate in the experience of “another dimension” far beyond the transitoriness of ordinary life – informed his attitude towards life and was conducive to his later appreciation of militaristic Bushidō-Zen and his admiration of the kamikaze pilots which he expressed even after World War II.6

|

Fig. 3 Bavarian infantry (postcard 1915) |

The Square

Immediately after World War I Dürckheim supported one of the far-right nationalistic Free Corps fighting against the Munich Republic. He also published nationalistic brochures and pamphlets as well as articles that warned against the Bolshevist world revolution.7

In 1919 he left the army and began to study philosophy and psychology in search of a new meaning of life. He and Enja von Hattingberg, his partner and later spouse, befriended the Austrian psychologist and philosopher Ferdinand Weinhandl (1896-1973), who at the time was working at the Psychological Institute at the University of Munich, and his wife, the teacher and writer Margarete Weinhandl (1880-1975). The four, who called themselves “The Square,” were not just two couples on friendly terms. Their joint activities were aimed at a religious transformation of their own lives and the lives of others.

Dürckheim shared not only philosophical, psychological and religious interests with the Weinhandls but also the experience of World War I as well as the ensuing nationalistic attitude nourished by it. Ferdinand, like Dürckheim, had voluntarily joined the army and became a frontline lieutenant, but a serious injury soon made him unfit for battle. Margarete had supported soldiers from the province of Styria in southeast Austria with simple verses and poems written in Styrian dialect, that were published in Heimatgrüße. Kriegsflugblätter des Vereins für Heimatschutz in Steiermark (“Greetings from Home. War pamphlets of the Association for Homeland Security in Styria”), a journal that was distributed free among Styrian soldiers.8

|

Fig. 4: Thrusting oneself into deadly danger in World War I |

The Weinhandls dominated the Square both intellectually and religiously. They were prolific writers well versed in the history and theology of Christian mysticism. Moreover, Ferdinand was interested in comparative religion. He referred to Friedrich Heiler’s comparative studies on prayer and on Pali-based, Buddhist meditation, and praised his subtle understanding of the inner relations between various religions.9 Interpreting the similarities between religious practices within different religious traditions outlined by Heiler, Ferdinand stated that the different stages of Hindu-Yoga, Buddhist meditation and Christian prayer are all based on the same psychological structure.10

In 1921, The Square moved to Kiel where they lived as a sort of commune, sharing a flat until 1924. During that time, Margarete published and interpreted the mystical writings of German medieval nuns.11 Ferdinand completed his habilitation thesis in 1922 at the University of Kiel and later got a professorship for philosophy there.12 He translated and edited the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola and published a small book on Meister Eckhart.13 In fact, it was he who introduced Eckhart to Dürckheim.14 “Every evening we would read Meister Eckhart,” Margarete noted in her diary.15 Dürckheim remembered: “I recognized in Master Eckhart my master, the master.”16 Meister Eckhart had great appeal for the German Youth Movement and the cultic milieu of the interwar-period in general. As a “German mystic” he also blended very well into the völkisch understanding of religion that was en vogue in Dürckheim’s circles.17 Like so many others Ferdinand Weinhandl saw in Eckhart an early manifestation of the deepest essence of the German spirit, its dynamism and “Faustian” activism.18

|

Fig. 5 Ferdinand Weinhandl |

During the Nazi era the völkisch interpretation of Eckhart continued. In his Myth of the 20th Century the NSDAP ideologist Alfred Rosenberg extensively cited Eckhart as the pioneer of Germanic faith. In 1936 Eugen Herrigel drew parallels between Eckhart and Zen in his article on The Knightly Art of Archery that became a major source for Dürckheim.19 Herrigel looks at Eckhart and Zen from the typical perspective of the protagonists of völkisch mysticism:

It is often said that mysticism and especially Buddhism lead to a passive, escapist attitude, one that is hostile to the world. […] Terrified one turns away from this path to salvation through laziness and in return praises one´s own Faustian character. One does not even remember that there was a great mystic in German intellectual history, who apart from detachment preached the indispensable value of daily life: Meister Eckhart. And whoever has the impression this ‚doctrine’ might be self-contradictory, should reflect on the Japanese Volk, whose spiritual culture and way of life are significantly influenced by Zen Buddhism and yet cannot be blamed for passivity and an irresponsible sluggish escapism. The Japanese are so astonishingly active not because they are bad, lukewarm Buddhists but because the vital Buddhism of their country encourages their activity.20

During the war Dürckheim was to call Eckhart “the man whom the Germans notice as their most original proclaimer of God”21 and he, like Herrigel, outlined the proximity between Eckhart and Zen on the basis of völkisch thought.

|

Fig. 6 Alfred Rosenberg and his “Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts” |

Before his first encounter with Eckhart, Dürckheim had already been deeply impressed by Laozi. The new popularity of Asian religions in Germany (after the Romantics at the beginning of the 19th century) began around 1900 under the influence of the Theosophists and the emergence of a neo-romantic “new mysticism.” It grew rapidly after the war with several translations of the Daodejing becoming available, the most widespread of which was by Alexander Ular.22 This book, together with translations of Laozi and Zhuangzi published by Martin Buber and Richard Wilhelm, unleashed a kind of Dao craze among intellectuals and artists of the Weimar Republic. Dürckheim describes his first contact with Laozi as a kind of ecstatic experience of enlightenment, prompted when his wife read the eleventh verse from Ular’s version out loud.23

Ferdinand not only undertook a theoretical study of religious exercises, but also introduced their practice to The Square.24 They experimented with different forms of meditation (sitting silently without an object or meditating on specific topics, probably influenced by Ignatius of Loyola, Coué´s autosuggestion and New Thought forms of meditation); spent certain days in silence and practised the daily examination of conscience.25 Outwardly they offered counselling sessions to people who contacted them, after having heard about the group because they were interested in their spirituality. One could say that The Square was a kind of model for Dürckheim’s work after World War II, and further foundations were laid here for his later interest in Japanese practices and the synthesis of spirituality and psychotherapy. During this period, Dürckheim also read a book on Buddhism by Georg Grimm that he held in great esteem.26

The Worldview of the Rightist Cultic Milieu

As strange as it may seem nowadays, the combination of new religiosity, interest in Asian religions, nationalist thought and an often antidemocratic attitude that had been formative for the young Dürckheim and also for the Weinhandls, was not exceptional at that time. They more or less shared popular views of the Weimarian rightist cultic milieu,27 which consisted of a large number of small organizations, reading circles, paramilitary groups and the so-called Bünde (leagues) with links to the German Youth Movement and the movement of life reform (Lebensreform). “The Bünde were uniquely German. What made them so during the years between 1919 and 1933 was the fact that neither the onlooker nor the participant could decide what they were. Were they religious, philosophical, or political? The answer is: all three.”28 Although The Square strongly sympathized with the Bünde, they deliberately decided not to organize themselves in that manner, but to continue to live as a small community focusing on personal transformation.29

The rightist cultic milieu was informed by several widespread ideas that also deeply influenced Dürckheim and his Square. Here only the most important ones can be mentioned.

|

Fig. 7 Ludwig Fahrenkrog: Die heilige Stunde (1918) |

The New Man

Many expected the breakdown of traditional European culture through World War I, and especially the post-war crisis of German society, to lead to a transformation of mankind, the arrival of a “new man.”30 Dürckheim described his post-war social environment: “[They were] all people in which, because of the breakdown of 1918, something new arose that also within me soon brought to consciousness something that in the years after the war everyone was concerned with: the question of the new man.”31

In a letter published in the commemorative volume on the occasion of Dürckheim’s 70th birthday, Ferdinand Weinhandl remembers the talks they had at the beginning of their friendship as “revolving around a magical centre.” It was “the question of transformation, that we examined again and again in our thoughts and talks, in our efforts and aspirations.”32 What Weinhandl does not tell the readers of the commemorative volume is the fact that in the 1920s the search for in-depth transformation of mankind and the millenarianism of the new man had a socio-political dimension. Leftist socialists merged them with their vision of a future society, and the right-wing counterculture we are talking about usually combined the dawn of the new man with the epiphany of the Volk and the longing for new leaders.

Socio-political Völkisch Thought

The adjective “völkisch“ (cognate with the English “folk”) means “related to the Volk, belonging to the Volk.“ In keeping with its meaning in present-day German, “Volk” is frequently translated into English as “people” or “nation.” Since the 1890s, “völkisch” had been used as self-designation of an influential German nationalistic and racist (anti-Semitic but also anti-Slavic and anti-romantic) protest movement, consisting of different organizations, groups and individuals in Germany and Austria. Building upon ideas that emerged within German Romanticism, for these individuals and groups “völkisch” and “Volk” took on a special meaning significantly different from “people” and “nation” – a meaning that made the word untranslatable into English and other languages. Therefore the original German terms are used.

|

Fig. 8 Cover of a journal of the völkisch Bewegung |

The völkisch movement imagined the Volk as a mythical social unity based on blood and soil as well as on divine will, underlying the nation state and being capable of bridging the class divisions within society. Furthermore, the Volk had a certain spirit or soul (“Volksgeist,” “Volkseele”) which comprised special virtues and certain ways of thinking and feeling. The traditional aristocratic way of legitimizing social and political rule through birth and descent was transferred from the noble dynasties to all members of the German Volk or Aryan race.33 The central aim of the völkisch movement was the purification of the Germanic race from alien influences and the restoration of the native Volk and its noble spirit.

Politically, the members of the rightist cultic milieu saw the Weimar democracy as a dysfunctional political system imposed by Germany’s enemies after the shameful defeat in World War I. They could see no sense in the discussions and quarrels between the political parties that for them only manifested the egocentrism of modern man. Additionally, they were afraid of Bolshevism and of social disintegration caused by class struggles. A politically crucial dimension of the hope for the coming of the “new man” was the chiliastic political vision of a Third Reich that would be able to overcome the inner turmoil of modern society.34 The only alternative to the degeneration of contemporary society and politics would be a völkisch reform of life, a spiritual, social and political renewal of Germany which would transform the country into a class-free holistic community of the Volk (Volksgemeinschaft) rooted in the homeland (Heimat) as well as in ancestral kinship (Ahnen) and ruled by charismatic leaders (Führer).

At the beginning of the 1920s, Ferdinand Weinhandl was still aiming at individual self-development and a mystical transformation free of political and social intentions. According to Tilitzki, Dürckheim and Wilhelm Ahlmann brought him into closer contact with Hans Freyer. This probably gave his concept of life-reform a völkisch twist.35 He also started to reflect on the necessity of new leaders (Führer) to imbue the spirit of the Volk with higher values. In a text from the middle of the 1920s he conceived the leader as an exceptional person who alone is capable of uniting the whole and thereby establishes true community: “So, our path leads us from the person to the people [Volk] and beyond that back to the person, to the exemplary individual, to the hero, to the idea of leadership [Führertum].”36 His völkisch leanings initially did not assume a radical right-wing form, and he continued teaching at social-democratic institutions and cultivated good relationships with colleagues who supported the republic.

For many members of the völkisch movement it was only a small step to become Nazis because National Socialism absorbed many elements of their worldview and presented itself as the political successful fulfilment of völkisch thought. In his Mein Kampf Hitler claimed that his party, the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, National Socialist German Workers Party) had been established to enable the völkisch ideas to prevail. The NS movement would therefore have the right and the duty to see itself “as the pioneer and representative of these ideas.”37 No wonder then that detailed biographical studies “show […] that the völkisch phenomenon and the Bünde phase were the place of transition to National Socialism.”38 After 1933 “völkisch” and “nationalsozialistisch” soon became synonymous whereas before then the Nazis were only one völkisch group among many.39

Like Dürckheim, Weinhandl and his wife joined the NSDAP in 1933. Dürckheim also became a member of the SA (Sturmabteilung, in English often called Stormtroopers or Brownshirts, a paramilitary group of the NSDAP) and Ferdinand joined the NSLB (Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund, National Socialist Teachers Association), the KfdK (Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur, Battle League for German Culture) and the NS Kulturgemeinde (NS Cultural Community).40 Margarete headed a department for worldview education (“weltanschauliche Schulung”) within the NS Frauenschaft, the women´s organisation of the NSDAP, and became a member of the NSDAP office for racial politics.41

Völkisch Religiosity

The religious concepts of the völkisch milieu have been researched intensively over the last decades.42 The multitude of mostly small communities and movements, which rarely existed for more than a few years, can be divided into two basic types: neo-pagan and völkisch Christian.43 Both were highly syncretistic in their anti-Semitic attempts to develop a racially specific, Aryan religion. The neo-pagan groups, a small minority, rejected Christian faith and either tried to revitalise ancient Nordic religions or searched for new forms of a Germanic faith. The völkisch Christians tried to extract the Aryan elements in the teachings of Jesus and constructed a history of German Christian faith from the German medieval mystics up to the present day.

|

Fig. 9 Pamphlet to promote the Deutsche Glaubensgemeinschaft (German Faith Community) (1921) |

Within Dürckheim´s Square we find the völkisch Christian attitude most clearly articulated by Margarete Weinhandl. Ferdinand´s interpretation of Eckhart points in the same direction. The available sources contain no information about Dürckheim’s early understanding of Christianity. His commitment to the Christian faith seems to have been weaker than that of the Weinhandls.

Margarete thought of the Jews as a race totally alien to the German Volk. They had their heroic heyday documented in the writings of the Old Testament, but afterwards they degenerated and this is the reason why they rejected the messiah. Through Luther’s translation, the Bible had become part of the German spirit and German religiosity. The treasures of the Old Testament and the message of Jesus had thus been preserved through the power of the German Volk, its poets and spiritual masters like Meister Eckhart, Jakob Böhme etc.44

Additionally Dürckheim and his friends adopted a perennialist approach to religion assuming that the main religious traditions share a single universal truth. Later Dürckheim remembered: “As early as in those days the question arose within me: Wasn’t this great experience that completely permeated Eckhart, Laozi, and Buddha essentially the same in each of them?”45

Similar to the Traditionalist School, they conceptualized the coming of the New Man as a return to the primitive man of pre-modern culture connected with the rediscovery of an ancient wisdom tradition that underlies all religions.46 Maria Hippius, Dürckheim’s second wife, stressed the affinity between The Square and the Traditionalists: “In these years other concurrent efforts existed that aimed at a ‘restoration of the human archetype’ by locating and reconnecting to a primordial tradition (Urtradition). René Guénon and Julius Evola may correspond best to what the circle of friends intended […].”47 Whereas Dürckheim knew Guénon only through his writings, he actually met Julius Evola, the Italian extreme right-wing philosopher and esotericist who harboured sympathies for the SS and the Romanian Iron Guard, whom he highly esteemed, in the 1960s.48

|

Fig. 10 Julius Evola |

The rediscovery of the ancient wisdom was supposed to bring about a renaissance of true religiosity in the form of mysticism. “Wherever religion is lived, it has the name mysticism, wherever wisdom is lived, it is called mysticism.”49 The Square understood mysticism as a way of life that is based on a radical transformation of the whole human being, brought about by the abandoning of one’s own will.

The völkisch approach to religion and the perennialistic concept of mysticism don’t necessarily contradict one another. In all likelihood the Square thought that German mysticism presented the core of all true religion in an extraordinarily pure form, a form that matched the superior national character of the Germans.

Holism

The Weimarian cultic milieu´s leanings towards totalitarianism were based on popular forms of holistic and organicistic thought. Wholeness (Ganzheit) was a widely used metaphor for what – according to völkisch worldview – had been lost in modern society and science and was to be regained by the “new man.” The radical conservative counterculture of the Weimar Republic was a holistic milieu that tried to rediscover the original wholeness of individuals by reintegrating them on different levels into larger “organic” wholes. According to common holistic ideology, individuals as well as social entities do not follow the laws of mechanics but an order whose prototype is the living organism. This kind of “organic thinking” was given a nationalistic connotation by the notion that the realization of “organic wholes” is something specifically German, whereas other Western countries (France, England, USA) are the homelands of “mechanical thinking.”50

Already in the Nazi era, Dürckheim would praise organic thought as being a protest “against the world of unleashed instrumental rationality, the proliferation of economics, technique and transport, against the tendency to reduce every process to its simplest mechanic formula, against the dissolution of the human being into a bundle of impersonal functions, the opposition of longstanding organic communities of blood and faith against special-purpose associations etc.”51 The appreciation of meditative practices and the invocations of mystical oneness with “the whole” that were so common in the Weimarian cultic milieu, should be understood in the context of this critical attitude towards the burdens of modern culture and the longing for personal, social and religious identity in a world experienced as fragmented and rapidly changing.

“Wholeness” and “organic thinking” were not just buzzwords within the rightist counterculture. “The desire for holistic thought was widespread in both the scientific and political reasoning of the Weimar Republic.”52 Many of the holistic academics participated in the völkisch scene and gave the milieu´s preference for organic wholeness a scientific outlook. It seems that in the late phase of the Weimar Republic, the majority of psychologists followed this line of thought. One of them was Dürckheim’s teacher and employer Felix Krueger, the successor of the famous Wilhelm Wundt at the University of Leipzig and founder of the so- called “Second Leipzig School,” also known as Holistic Psychology (Ganzheitspsychologie) – probably the best example for the holistic orientation of German psychology before 1933.

Felix Krueger’s Holistic Psychology

In 1925, Dürckheim, who had completed his Ph.D. in psychology in 1923, became an assistant at the Institute of Psychology at the University of Leipzig. He worked there until his habilitation in 1929/30. It is quite obvious that Dürckheim obtained this position not only because of his qualifications but also because of his participation in an academic right-wing network. Hans Freyer, the radical conservative philosopher and sociologist, who had been one of his teachers in Kiel and had in the meantime switched to the University of Leipzig, played a crucial role in this appointment.53 It was he who recommended Dürckheim to the director of the Institute of Psychology, Felix Krueger.

Since the end of World War I, Krueger’s Psychological Institute was considered to be a “völkisch cell” with a strong nationalistic bias, whose political activities stirred hostilities within the city council and even the German government.54 Krueger was a leading figure within the völkisch oriented Fichte-Gesellschaft (Fichte Society). As a busy lecturer, he played an important role within a large nationalistic educational network and thus had contacts with many patriotic associations and völkisch groups. From 1930 onwards he also lectured in the NS-student-association (Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund) and in the NSLB. Although his thought was close to National Socialism, and he had signed the recommendation to vote for Hitler published by German academics in November 1933, he nevertheless did not become a member of the NSDAP.

|

Fig. 11 Felix Krueger |

Krueger’s psychological theory had a “pronounced ideological accent” as it was meant to contribute to a renewal of the community of the Volk (Volksgemeinschaft).55 Especially from the late 1920s onwards he extended the range of his psychology to social life. His concept of community falls in line with the then very popular distinction of Gemeinschaft (community) as a traditional organic social unit and Gesellschaft (society) as a contractual association of individuals, predominating in modern times.

The ideological position of Krueger is clear to see, if one looks at how he constructs the relationship between the community as a whole and its members. He simply transferred his earlier theory of the dominance of the whole to social structures.56 “Krueger´s theory does not recognize the interaction between part and whole, rather only the law of the dominance of the whole; in the area of society it appears as the superimposition of the community over the individual and the subordination of the individual to the community.”57 It is this totalitarian bias that accounts for the affinity between Krueger’s thought and Nazism.

Dürckheim’s NS Thought and Völkisch Religion

Like many other members of the völkisch milieu, Dürckheim believed that Adolf Hitler and the Nazi movement would bring about the arrival of the new man. “Through Adolf Hitler the Gods have given to the German People […] the power to awaken fellow Germans in an infectious movement and transform them towards this new man.”58 It was Krueger’s social holism in particular that helped him to shape his Nazi philosophy in the years after 1933. As Geuter has pointed out, Krueger himself only made programmatic statements on community. It was Dürckheim who elaborated a systematic holistic psychology of community life based on the theories of the Leipzig School in his articles Gemeinschaft (Community, 1934); Dürckheim´s contribution to the Festschrift in celebration of Kruegers 60th birthday; and the openly national-socialist Zweck und Wert im Sinngefüge des Handelns (Purpose and Value as Constituents of Meaningful Action, 1934/35).

|

Fig. 12 Being one with the greater Whole: May Day Celebrations Berlin 1937 |

Like Krueger, Dürckheim conceives of community (Gemeinschaft) as the basic social unit. Communities are “closed wholes”59 characterized by certain value-systems that have absolute validity for all members. From Krueger he also borrowed the principle that the true relationship between the whole and its parts is the total subordination of the parts. “The being of the whole is the imperative of its parts; whatever is useful for the whole is a law for the individuals.”60 One of the dangers that threaten their health and that members of communities have to fight back against is “the infiltration of foreign bodies (racial question!).”61 The natural values of the individuals reflect their racial origin and the blood- and fate-based membership in the organic wholes of homeland, family and Volk.

The value-oriented life of the soul depends on its inborn and racially conditioned nature. The order of its perennial values is based in certain fundamental life units with which the soul is connected by fate, an order that is defined by the claims made by these units to sustenance, realization and perfection.62

According to Dürckheim, the Volk had lost its domination over its parts in the Weimar Republic. The leaders of the country had been alienated from the higher whole, and, even worse, non-Germans, especially Jews, had exercised significant influence.63 “It must be stressed again and again that the NS revolution was the revolution of the whole against its disloyal parts.”64 It was only Hitler’s wake-up call that reunited the German Volk and renewed the basic values of its life.65

For Dürckheim, the reawakening of the Volk among the Germans had practical consequences. Hitler also “steeled their will to dominate reality.”66 He explicitly defends the brutality of the Regime against individuals unwilling to subordinate themselves to the realization of what the Nazis defined as the interests of the larger whole. The NS man possesses “the power to be radical that does not recognize sentimental care about painful concomitant effects that everywhere affect individuals wherever the realization of a larger whole is at stake. The accusation of harshness, which is time and again levelled against National Socialism, is a typical statement of a sort of mankind that cares about individuals and has lost sight of the superior whole.”67

The “image of the fighter driven by fanatic faith” is in Dürckheim‘s view the role model for the type of human being that National Socialism aims to produce.68 “German soldiership could well be the starting point of a comprehensive realisation of the German mind.”69

|

Fig. 13 Training of the Waffen-SS |

For him it was through National Socialism that the “German worldview” (deutsche Weltanschauung) became a political force for the first time. This worldview clearly shows the characteristics of a religion as well, and therefore Dürckheim also calls it “German faith.” The source of German faith was the “unshakable belief in the German Volk” that Adolf Hitler implanted in his fellow Germans, and this belief implied the commitment of Germans to Germany as something that they accepted to be holy.70 Dürckheim describes this faith as based on the individual experience of a higher reality, contrasting this with the mere “subjugation to a dogma.” He thus connects the topos “mysticism versus dogmatic religion” and the anti-church sentiment that had been quite widespread within the “new mysticism” of the Weimarian cultic milieu with his NS-worldview:

As the centre of this faith we find the breakthrough of the great subject Germany [das große Subjekt Deutschland] within the individual. Therefore faith in the NS-sense does not mean subjugation to a dogma, but the inspiring force coming from the joyful experience of a higher whole, that resides within you and wants to become reality through you – and this with such a power that one cannot help but to serve this higher will and sacrifice everything that is only personal.71

|

Fig. 14 NS Christmas Cult: Goebbels and family |

The motive of (heroically) abandoning one’s own will and surrendering to the greater whole functions as a link between Dürckheim’s militarism and political totalitarianism on the one hand and his preference for mysticism on the other. He constructs the Volk as a trans-temporal divine essence (“eternal Germany,” and later, “eternal divine Japan”) that every individual should incarnate by giving up selfishness and surrender to the egoless functioning within the whole. Service to the community of the Volk and obedience towards its leaders who represent the will of the whole serve as a paramount connection to the ultimate divine reality. As the Volk is the primary revelation of the divine, the main religious task of its members is to contribute to its development and most powerful manifestation.72

One would think that such a theology of the Volk is hardly compatible with racism. But this is not the case. For Dürckheim certain racial conditions are part of the eternal essence of the Volk. Every Volk has the task of manifesting the Divine according to its own racial characteristics. It is thus a holy duty “to maintain the racial substance and protect it against any danger.”73

Introduction to Dürckheim’s Wartime Writings

In 1939 and 1940 – obviously as an outcome of his first stay in Japan (1938-1939) – Dürckheim published four articles related to Japan in Germany with the 1940 Das Geheimnis der japanischen Kraft (The Secret of Japanese Power) as a summary of his previous study of Japanese culture and a basis for the explorations of his second stay.74 The journals that published these articles were all deeply connected to the regime. These included: 1) Das XX. Jahrhundert (The Twentieth Century), financed by the German Foreign Office; 2) Berlin – Rom – Tokyo, a “monthly journal for the deepening of the cultural relationships between peoples of the global political triangle,” also financed by the press department of the Foreign Office and meant to provide publicity for the Tripartite Pact and establish a sense of communality between the Germans, Italians and Japanese; and 3) Zeitschrift für deutsche Kulturphilosophie (Journal of German Philosophy of Culture). The third publication was the NSDAP-conformist successor of Logos. Internationale Zeitschrift für Kulturphilosophie (Logos. International Journal of Philosophy of Culture) that was forced to cease publication in 1933. It propagated a völkisch philosophy of culture in line with the cultural politics of the Nazis.

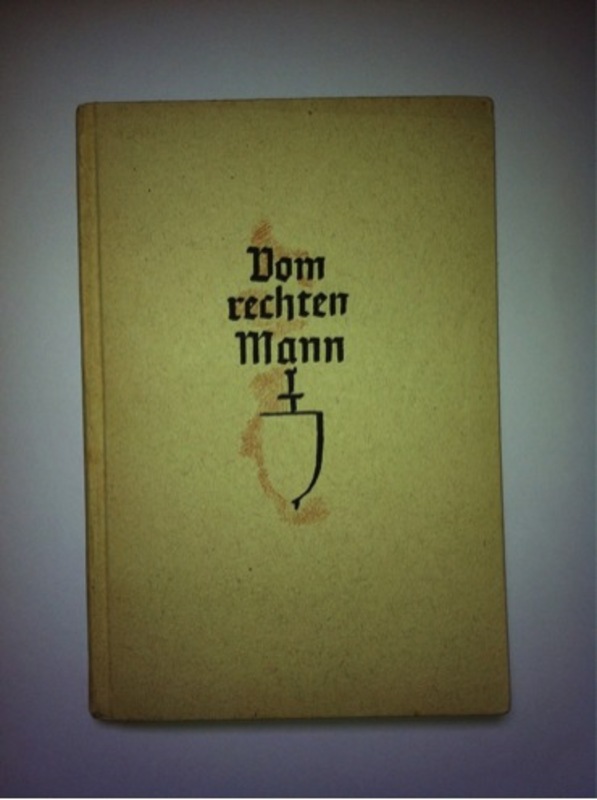

His booklet Vom rechten Mann. Ein Trutzwort für die schwere Zeit (On the Righteous Man. A Word of Defiance for Difficult Times), published in 1940, was a kind of devotional book written for German men (in wartimes and other difficult situations). Besides the political situation, Dürckheim may have had some personal reasons for writing it given the fact that at the end of 1939 both his first wife Enja and his father died.75 According to the dedication, he finished it in January 1940, the month of his second departure to Japan. The question as to whether this book was influenced by Japanese thought will be discussed below.

During his second stay in Japan (1940-1947) Dürckheim did not publish anything in Germany. There are two reasons for this: 1) For propaganda reasons he tried to launch as many NS-related articles as possible in Japan, and 2) communication between Germany and Japan had become more and more difficult as the war proceeded. His most voluminous German work published during the Nazi era was only available in Japan: Neues Deutschland. Deutscher Geist (New Germany. German Spirit, 1942).76 Dürckheim tells us in his preface to the first edition of this book that its chapters were originally articles written for different Japanese journals that had been translated into Japanese by Hashimoto Fumio. Subsequently, the German original texts were published in two collections: Volkstum und Weltanschauung (Völkisch Tradition and Worldview, 1st ed. 1940; 3rd ed. 1941) and Leben und Kultur (Life and Culture, 1st ed. 1941). According to Dürckheim, Neues Deutschland. Deutscher Geist contains the largely unaltered original German versions of the articles of both smaller collections. I will quote from the second “improved“ edition of this book, published, like the first one, in 1942.77 In that same year a Japanese version of Neues Deutschland. Deutscher Geist was released.

|

Fig. 15 Dürckheim’s article on Shujo-Dan |

In 1942 Dürckheim also published an article entitled ‘Europe’? in The XXth Century, the English counterpart of Das XX. Jahrhundert, a propaganda journal for East Asia financed by the German Foreign Ministry.78

Several other texts written between 1940 and 1944 were only published in Japanese. At least some of the original German manuscripts of these publications are archived at the family archives of the Counts of Dürckheim-Montmartin at the Landesarchiv Speyer/Germany whose Karlfried-Graf-Dürkheim section is now unfortunately inaccessible for non-members of the family. Gerhard Wehr – probably the last person who was allowed to work in the archives – mentions the existence of the German manuscript of Maisuteru Ekkuharuto with the title “Meister Eckhart” (85 pages) and a manuscript “Der Geist der europäischen Kultur – Ein Beitrag zur Geophilosophie” (The Spirit of European Culture – A Contribution to Geo-Philosophy) from 1943, which, at least according to its title, seems to be the German version of Yoroppa Bunka no Shinzui (The Essence of European Culture).79 Wehr also confirms the existence of several other German manuscripts from that period in the archive without going into detail.

Religion in Japan from a Völkisch Perspective

As one might expect from what has been stated above, Dürckheim´s thought does not so much address religion in Japan per se, but more the Japanese as a Volk and the sources of its astonishing military power, the success of its dictatorial regime and its impressive völkisch unity. For him the Volk had absolute priority over all other issues and so he did not show any interest in interreligious matters but wanted to contribute to an inter-völkisch understanding, zwischenvölkisches Verstehen, as he literally put it. In this regard he considered world religions to be an obstacle:

|

Fig. 16 Graf Dürckheim (1940) |

Christians, Buddhists and humanists of all nations [aller Völker] may coincide with regard to certain human basic requirements, and they may feel the obligation to understand, to help and to love each other on a personal level. But all this has nothing to do with a mutual understanding of völkisch mentalities and their necessities. On the contrary, till today the world religions by virtue of their transnational mission [aus ihrer übervölkischen Mission] avoided the unconditional acceptance of völkisch values and necessities of life. Actually, most of the time they fought against the passionate commitment to one’s Volk and – hereby inhibiting all understanding – fought against it as pride of race and chauvinism that contradict their basic requirements.80

Shinto and Japanese Buddhism are considered to the extent they fit the divine völkisch nature of Japan and help to strengthen the historical manifestation of the eternal Japanese spirit. Even when he compares Meister Eckhart and Zen this is not meant as a comparison between a form of Buddhism and a certain kind of Christian theology and spirituality but as a reflection of the relationship between Japanese völkisch religion (inspired by Buddhism) and German völkisch religion (inspired by Christianity). Buddhism was a creative challenge to the Japanese that ultimately helped them to discover their true völkisch nature and its innate religiosity. By the same token, the influence of Christianity in the long run helped to clarify the German worldview:

Just as Buddhism made its way to Japan, Christianity came to Germany from the outside. […] Christianity is not the German worldview, nor is Buddhism the Japanese. The confrontation with these world religions that claim validity for the whole of mankind and relate to the redemption of the individual brought to Japan and Germany compulsory clarity in respect to the (self-)awareness of the essence and the living wholeness of the ‘Volk’ and thus to the völkisch worldview.81

This of course is meant as “gaining strength through strong adversaries” but, as we will see below, it also comprises the positive reception of certain elements from world religions. For völkisch religions they play a similar role to what Dürckheim calls the “international world civilisation” (basically consisting of modern science and technology) for völkisch cultures. Both are dangerous for the völkisch spirit but to a certain extent also useful and inspiring.

The Japanese People as an Exemplary Volk

Dürckheim describes Japan as a country confronted with the same problems as the Nazi movement was at that time. In his view, modern developments, such as industrialization, rationalization, the influence of the Western – especially the American – attitude of individualism and profiteering, threatened the realisation of the eternal essence of both peoples.82 “It is the spirit that connects us with Japan, this spirit, which, born out of the völkisch substance and the nation’s will to survive, in Japan as well as here in Germany fights against the alien and brings to bear its particular nature.”83 Similar to Germany, the dangers of modernity as well as the threat of war stimulated Japan’s völkisch power and the implementation of political structures in keeping with the Japanese spirit:

Japan today is just beginning to unfold its völkisch power. And this is because Japan’s traditional faith, far away from being ‘replaced’ by a modern one, progresses from the stage of a religious basis of völkisch life and a binding force for specific classes to the political self-confidence of the whole Volk.84

This passage reveals the core of his view of Japan’s “hidden force” and the specific function of religion that interested him. For Dürckheim the successful politics of the future world was to be inseparably linked to the awakening of völkisch identities based on a religious attitude that unconditionally supports the world’s leading totalitarian states. Accordingly, the primal source of Japan’s power was the politicizing of its original faith. He recognized the rise of a völkisch religion consisting of a politicized mixture of Shinto and Buddhism that unites the whole nation and functions as a basis of legitimation for the Japanese state and its policies. In August 1941 he noted in his diary: “My research work continues and recently in particular has turned towards the religious foundations of Japanese power, that is to Shinto and Buddhism.”85

Dürckheim sees the divine völkisch spirit and its will to live as connecting Germany and Japan. “In spite of all differences regarding the contents of faith and the forms this faith creates, through its iron will to self-realisation this spirit is related to ours.”86 Moreover, the German Volk is even able to understand Japan better than any other Volk. In this regard Dürckheim refers to Hermann Bohner’s “masterful introduction and commentary” to his translation of the Jinnō shōtōki (Chronicles of the Authentic Lineages of the Divine Emperors).87 Indeed, Bohner wanted to demonstrate the inner affinity between Germany’s Third Reich and the Japanese tradition in order to bring the Jinnō shōtōki closer to his German audience.

In doing so, he likened Kitabatake´s work to Moeller van den Bruck´s Das dritte Reich, maintaining both were connected with the same ultimate question of ‘who we are.’ Bohner furthermore claimed that both texts were ‘conversations with God,’ ‘self-dialogues,’ and ‘conversations with the eminent Us.’ He portrays their apparently similar contents as well as both author’s experiences in highly emotive terms: ‘As though by a gigantic, transcendent epiphany, a Daemonion, a personality, that like every Ego is real and yet non-tangible, each author is faced by the personality of his own nation.’88

Bohner’s paraphrases of Moeller van den Bruck and Kitabatake come very close to Dürckheim’s deification of the Volk.89 He must have read Bohner’s summary of the beginning of the Jinnō Shōtōki with great sympathy: “Before China was (for Japan), before India was, before Kong [Confucius] and Buddha had come across the sea, there was Japan. It was what it is and what it will be: from the Deity it was, the divine seed was in it.”90 It is interesting to note that in Dürckheim’s Nazi articles written prior to his first stay in Japan, he had already mentioned religious feelings towards the Volk, albeit in a somewhat cursory manner. Japanese influences may have strengthened this dimension of his thought.

|

Fig. 17 Albrecht von Urach: Das Geheimnis japanischer Kraft (1942) |

In any case, for him the confluence between the traditional völkisch spirit and modernity was more advanced in Japan than in Germany, and he implicitly suggests that Japan sets a good example for the Third Reich in several ways. For him, Japan’s superiority lay in the fact that on the East Asian island the process of industrialisation is carried out by people who had not been infected by materialism and who had not given up their traditional way of life. The cult of the Emperor-God (J. Tennō) – unfortunately lacking in Germany – helped keep the old Japanese identity and worldview alive and visible throughout the ages.91 So despite their modernization, the Japanese still have strong ties to family and dynasty.92 Individuals consider themselves “with exemplary naturalness to be only a serving part of the higher life-units.”93

In the Germany of his time, by contrast, individualism as well as the materialistic spirit of both capitalists and proletarians were much stronger. Dürkheim complains that discussions on the individualistic understanding of freedom had not yet come to an end. The Germans, he says, are just about to reacquire the knowledge that liberty primarily means being free from oneself and therefore being free to perform community service. Dürckheim admits that contemporary Japan also has to face the “problem of freedom in a Western sense”:

But after all “individualists” still occur quite rarely. They are limited to certain social circles and individualism is a beacon to a world that didn’t know this phenomenon before, never idealized or philosophically legitimised it, and now fights against it to the bitter end.94

Dürckheim underlines the affinities between both cultures to such an extent that one sometimes gets the impression he thinks the Japanese would be the better Nazis. He was but one among many (academics as well as journalists) in the German-Japan discourse who praised Japan as one if not the exemplary Volk. This tendency was seen in the August 1942 Situation Report of the SS’s Security Service as a problem. The report states that the many comparisons between the successful non-Christian religious worldview attitude towards life, politics and warfare in Japan and the religious worldview situation in Germany have caused certain developments that make it necessary to gradually correct the image of Japan:

The former view, that the German soldier is the best in the world has been confused by descriptions of the Japanese swimmers who removed mines laid before Hongkong, or the Japanese pilots who, with contempt for death, pounce with their bombs on enemy ships. This has partially caused something like an inferiority complex. The Japanese look like a kind of ‘Super-Teuton’ [Germane im Quadrat].95

Dürckheim, however, is deeply convinced that a mutual enrichment between Germany and Japan could and should take place. With two different theoretical models he explains how this inter-völkisch encounter could work. The first model rejects direct borrowings between different völkisch cultures. “Just as it is impossible to shift Mt. Fuji to Europe and the Rhine to Japan, it is impossible to mutually transfer the essentially Japanese and the essentially German.”96 Nevertheless, the study of a non-transferable alien culture is able to stimulate deep cultural growth because it sharpens insight into the principles of one’s own culture, and it is able to inspire the rediscovery of some of its elements that were long lost.97

The second model of inter-völkisch relationship concedes the possibility of direct imports from an alien Volk and takes the reception of Zen Buddhism in Japan as an example of this.

The Integration of Foreign Elements into a völkisch Weltanschauung: Zen’s Contribution to Yamato-damashii

Whereas Dürckheim, as noted above, usually emphasized that the Volk is a “closed whole,” his reflections on Japan outline that it is not a completely closed entity like a concrete block, but possesses a limited openness that in some way resembles the relation between an amoeba and its surroundings. He distinguishes three kinds of “healthy” reactions to the foreign within Japanese history:98

- Alien elements that fit have been merged with the original völkisch substance (e.g., Buddhism and Chinese culture).

- Alien elements that did not fit have been withdrawn or at least suppressed (e.g., Christianity).

- Alien elements that did not fit, but proved to be necessary for the self-preservation of Japan were integrated without damaging the inner essence of the Volk in the long run (European Spirit, technical achievements).

For Dürckheim, Japan’s relationship with the outside world is a paradigm of how a healthy Volk with a strong “racial instinct” behaves. Japanese contacts with other nations and cultures deepened its self-knowledge and strengthened its power. His differentiation between several ways a Volk can relate to foreign Völker is important because it allows for intercultural contacts and influences to be affirmed on the basis of völkisch thought. As we will see, his goal seems to have been to integrate Japanese elements into the Teutonic way of life. But let us first consider what he thought to be the contribution of Zen to the Japanese völkisch culture.

For him the Japanese racial instinct, faith or worldview is a mighty “current of life” that carries the Japanese nation along and guides it beneath all conscious activities. The Japanese word for it, he tells his readers, is Yamato-damashii (usually translated as the “Heart of Yamato,” or “Japanese Spirit”).99 According to his most elaborate analysis in Das Geheimnis der japanischen Kraft (The Secret of Japanese Power) Yamato-damashii had four foundations:100

1. Tennō: the center of the Empire, personification of the Volk, its unity and its divine origin.

2. Bushidō: the way of the knight, the samurai.

3. Loyalty and piety towards one’s ancestors, parents and superiors.

4. Freedom as detachment from life and death.

Since Zen Buddhism comes into play in 2) and 4), the author will focus on these points in the following.

The only source concerning Zen that Dürckheim refers to in Das Geheimnis der japanischen Kraft is Suzuki’s Zen Buddhism and its influence on Japanese Culture (1938).101 The author is not aware of any other Zen-related literature that Dürckheim referred to in his published wartime writings. It is certain that he also knew of Herrigel’s article on The Knightly Art of Archery. Furthermore, as detailed in Part III, he was later introduced to Zen-related literature and texts written by Yasutani Haku’un and translated for him by Hashimoto Fumio.

From Suzuki and Herrigel, Dürckheim learned that Zen is a Buddhist sect that – like every form of Buddhism – searches for enlightenment through meditation, but differs from other Buddhist schools for three reasons which make Zen especially interesting for Dürckheim:102 1) its denial of every dogma,103 2) its aspiration for a direct relationship to the absolute,104 and 3) its emphasis on the practice of this relationship in daily life, work and service.105

For Dürckheim, Zen is the best example showing that Japan does not fit the characterization of Asian mentality as dominated by passive contemplation. Instead, Zen helped to create the typical Japanese synthesis of a “passive experience of God” with “willpower and determined action.” He emphasised that Zen monks had been among the great teachers of the samurai spirit, which had evolved during the first military rule of Japan in the 13th century.106 Then he continued:

It is good to know that today perhaps 50% of the Japanese officer corps have a more or less close relationship to Zen Buddhism, and this means knowledge of the power of the motionless mind, the still heart. It also means a personal relationship to the demands of Zen-Buddhist culture, a culture which recognizes the fulfilment of life in the validation of perfect harmony – symbolically expressed in the tea ceremony, but ultimately in everything, especially in human relations.107

Note that harmony in accordance with Dürckheim’s holistic thought means the whole having perfect control over its parts. Accordingly, Zen in Dürckheim’s view is a practice that unites the different classes of the Japanese Volk. Not only military officers, but also Japanese businessmen, industrial workers and peasants are open to the Zen-influenced meditative experience and therefore know “the secret of ‘the inner space’.”108 He illustrates this with an observation from Japanese daily life:

Every Westerner notices how silently the Japanese often sit or kneel. It is as if they have a secret space to live in, into which they can withdraw at any time, and in which they experience something that noisy reality is never able to give. They somehow know about the silent and unmoved heart that reveals the true independence of human beings from things external.109

The experience of an inner space enables the Japanese to be content with whatever social conditions they live in, to be happy even if they suffer from poverty and hard work as workers and peasants, and to stay calm even when risking their lives for their country as soldiers. The metaphor of the “secret inner space” is notable because it does not seem to belong to Zen vocabulary. The author found only one passage in Suzuki’s Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture that resembles this metaphor and might have influenced Dürckheim. Suzuki reflects upon the significance of the tea cult for the Japanese warriors “in those days of strife and unrest when they were most strenuously engaged in warlike business” and needed a respite from fighting and time to relax:

The tea cult must have given them exactly what they needed. They retreated for a while into a quiet corner of their Unconscious symbolised by the tearoom no wider than ten feet square. And when they came out of it, they felt not only refreshed in mind and body, but most likely had their memory renewed of things which were of more permanent value than mere fighting.110

The “inner space” whose cultivation is fostered by Zen practice is connected with the fourth characteristic of Yamato-damashii: freedom from passions like fear and sorrow as well as from mental unrest – a state that is attained by letting go of all forms of clinging to the world:

Regarding this, the Japanese possess a religious source of power in the form of their Buddhist faith […] Expressed in our categories one cannot but call this source a special relationship to the absolute and an independence from life and death that results from closeness to the absolute.111

This independence is, according to Dürckheim, a Buddhist virtue and at the same time the most basic source of the transpersonal loyalty that the Japanese time and again prove in their service to both family and Volk. Herrigel already had expressed exactly the same view in his 1936 article on the knightly art of archery:

For the Japanese it not only goes without saying that they integrate themselves smoothly into the organic orders of their völkisch existence – they even sacrifice their lives for them in a detached and modest way. And here only the fruit of Buddhist influence and therefore the subconscious educational value of the Zen-based arts become evident: from this innermost light death and even suicide for the sake of the fatherland get their sublime consecration and in a most fundamental way lose all horror.112

The results of Dürckheim’s article on the mystery of Japanese power are in accordance with Suzuki’s theory of the fundamental significance of Zen for all of Japanese culture and Herrigel’s high evaluation of the educational value of Zen- based arts. Dürckheim tried to show that the practice of Yamato-damashii is deeply rooted in Zen insights and attitudes, and therefore Zen ultimately appears to be the most significant expression of the Japanese völkisch spirit and an essential resource of Japanese power. Similar to Suzuki, and perhaps even stronger than him, he underlined the connection of the samurai to Zen. The positive contribution Zen made to the military and economic strength of Japan and to the inner unity of the nation were of crucial importance for Dürckheim’s positive evaluation of this form of Buddhism.

Possible Japanese Influence on Dürckheim´s Vom rechten Mann

As mentioned above, in 1940, just as he was about to travel to Japan again, Dürckheim published a small booklet meant to be a kind of handbook for German men in difficult times (especially in wartime). There the ideal righteous man is described as a man of honor (Ehrenmann), a man of God (Gottesmann) and a man of the Volk (Volksmann). Describing the virtues of the righteous man in relation to himself, to God and to his Volk, Dürckheim reveals the ethical and spiritual principles of his völkisch world view. The booklet consists of many small chapters whose style is reminiscent of the German translations of the Daodejing.

|

Fig. 18 Karl Eckprecht (pseud.): Vom rechten Mann |

There are other “orientalizations” that distinguish this text. For example, there is the striking importance of the metaphor of the sword. Dürckheim wrote:

The righteous man does not revolt out of selfishness. But if his honor is concerned, if his nation is in danger or God’s concern is violated within himself or within the World, then this calls him to fight and transforms him into a sword. […] then a kind of willpower arises that does not take care of itself but knocks down everything that stands in his way.113

This sequence probably resonates with Suzuki’s philosophy of swordsmanship and his use of “the sword” as a symbol for the life of the samurai, for his loyalty and self-sacrifice. For Suzuki the sword fulfils a double function. First, it destroys anything that is opposed to its owner’s will in the spirit of patriotism and militarism. Second, it is the annihilation of everything that stands in the way of peace, progress and humanity. The sword symbolizes “the spiritual welfare of the world at large.”114

Being a gift of God the sword (as a weapon as well as by virtue of its symbolic meaning of unconditional determination and vigour) represents something holy for Dürckheim. “The strongest will, the purest fire and the sharpest sword – out of God do they come to the righteous man.”115 And of course Dürckheim’s sword, like Suzuki’s, destroys for the benefit of mankind. “His sword is shiny, hard and merciless. It’s all for a good cause and this requires that one not slacken in the fight.”116 In Neues Deutschland. Deutscher Geist Dürckheim, very similar to Suzuki, was to call the sword “Hüter des Heiligen” (guardian of the holy).117

The metaphor of the sword was certainly not new to Dürckheim when he came across it in his encounters with Japanese culture. It is well known in German culture too, especially in Nazism. In Neues Deutschland. Deutscher Geist Dürckheim says that “the connection of lyre and sword” is something typically German.118 Moreover, in Das Geheimnis der japanischen Kraft he sets forth the proposition that the unity of lyre and sword, poetry and military spirit, could well be the deepest common ground of the völkisch spirit of both Germany and Japan.119 “Leier und Schwert” (Lyre and Sword) is the name of a volume of poems written by the 19th century poet Theodor Körner, who was held in high esteem by the Nazis. In Hitler’s Mein Kampf, a book that Dürckheim thought very highly of, the word “sword” is used 27 times as a synonym for “weapon” or “military force.” Hitler contrasts the virtuous “nobility of the sword” (Schwertadel) with the corrupt Jewish “nobility of finance” (Finanzadel).120 But it seems that Suzuki’s Zen-empowered samurai and other Japanese sources inspired Dürckheim to elaborate on its symbolism.

Most of the religious parts of the book use words and phrases taken from the language of Christian piety albeit without reference to Christ, Mother Mary, the Trinity and other theological features i.e., in the sense of a völkisch religiosity influenced by Christianity. The term “die Große Kraft” (the Great Force) that he uses four times, three of which with quotation marks, does not fit into this vocabulary.121 To give but one example: “The righteous man has a cheerful heart and a mind which is always free in the depth of the soul. . . . There he is carried by the Great Force and from there he carries and overcomes everything.”122 Where did this expression come from?

In 1964 Dürckheim published a collection of texts as Wunderbare Katze und andere Zen-Texte (Marvelous Cat and Other Zen texts). The text from which the collection derived its name Marvelous Cat is a training manual used by a fencing school whose author according to Dürckheim was an early seventeenth century Zen master named Ito Tenzaa Chuya. Dürckheim writes that the manual had been given to him by “my Zen teacher” Admiral Teramoto Takeharu. Admiral Teramoto was a professor at the Naval Academy in Tokyo and also a Japanese fencing (kendō) adept. The text is about “das Wirken, das aus der großen Kraft kommt” (the kind of action that comes from the Great Power). “Große Kraft” here functions as translation of the Japanese ki no sho.123 Dürckheim probably got his hands on this text during his first stay in Japan and took the phrase from there when he wrote Vom rechten Mann.

The expression “inner space” with which Dürckheim characterized Zen experience also reappears in Vom rechten Mann. He used it to describe a form of meditation already resembling the centering of the body in the hara that was to become so important in Dürckheim’s post-war writing. It also partly sounds like a paraphrase of Suzuki’s recreation of the warriors’ “in a quiet corner of their Unconscious”:

When things become really bad and unrest threatens even his heart, then he turns inward and locks himself up in the innermost space of his soul. This space is his secret. There he recollects himself in his deepest centre. Totally silent he settles himself, lifts his heart and lets his mind and senses calm down again in God. Even in the middle of the greatest turmoil he always finds the moment to let go of everything, to lower the shoulders and breath deeply. And he does not stop this until he experiences the power of the great centre again.124

The different points that in Dürckheim’s view distinguish Zen from other schools of Buddhism were also essential to his German völkisch religiosity which was supposed to support the Führerstaat and its policies. His concept of inter-völkisch contacts allowed him to affirm the integration of elements from foreign religions and cultures into the German völkisch worldview. He thus proceeded to introduce ideas from what he perceived to be the Japanese völkisch worldview and to transform them in such a way that they would fit and enrich the Nazi-German worldview. On the one hand, transnational religions like Buddhism were only of minor importance to him compared with völkisch religious worldviews. On the other hand, he followed Suzuki and Herrigel’s analysis of Zen’s influence on Japanese culture, arguing that as a völkisch transformed Buddhism it was of essential importance to Yamato-damashii.

That he began to blend his own völkisch religiosity with Zen concepts can also be seen from an undated letter to a Japanese friend quoted by Wehr. Dürckheim wrote:

If I reflect upon the ruling classes of the future, well, I think, they will perhaps revolve around something like a political, i.e., völkisch satori, which is at the same time a super-völkisch satori, that is to say, around a spiritual breakthrough towards ultimate reality – but a breakthrough in which the searching subject is not the individual but a greater self which attains consciousness within the individual.”125

Wehr interprets this passage as evidence of Dürckheim having overcome Nazi ideology during his stay in Japan (actually the only one he could find). According to his interpretation the “greater self” mentioned in this text corresponds to C. G. Jung’s concept of the “self” as a goal of the process of individuation. But the text fits perfectly with all we know about Dürckheim’s Nazi worldview, if one sees the “greater self” as referring to the Volk, as the whole passage suggests. Once again the awakening to ultimate reality and the awakening of the Volk within the individual are identified with each other in a völkisch-super-völkisch enlightenment.

Conclusion

One could say that Dürckheim, like the Japanese protagonists of the Zen-Bushidō ideology, instrumentalized religion in the service of political totalitarianism. He did do so not as a secularized non-believer but as someone for whom the German and Japanese Volk had religious significance because he understood them and their political systems as manifestations of the Divine. Dürckheim maintained that their völkisch worldviews as a reflection of the reality of the Volk should be endowed with a genuine religious dimension.

Dürckheim obviously did not intend a kind of new institutionalized church-like national religion for Nazi Germany, be it neo-pagan or völkisch Christian. When the state represents the Volk and the Volk is the highest revelation of ultimate reality then religious organisations become superfluous. Political rituals and state holidays take the place of religious rituals and feasts. Out of this came Dürckheim’s sympathies for state-supported Shintō, the Japanese state’s ideology and cult. He probably envisioned adding spiritual exercises based on the model of Japanese Zen arts to these quasi-religious forms of expression of the holy Volksgeist – at least for the German elites.

Dürckheim’s Nazi thought is a good example of the enormous aggressive potential of such a politicised religiosity. A religiosity that would stop short of nothing should the display of a nation’s power and its rulers be at stake.

Karl Baier is a professor in the Department for the Study of Religions, University of Vienna. He holds a Ph.D. in philosophy and an M.A. in Catholic Theology. Major Writings include “Yoga auf dem Weg nach Westen” (1998), a book on the history of Yoga in the West, and his habilitation thesis “Meditation und Moderne” (Meditation and Modernity) that was published in two volumes in 2009. Karl Baier is a member of the European Network of Buddhist Christian Studies.

Recommended citation: Karl Baier, The Formation and Principles of Count Dürckheim’s Nazi Worldview and his interpretation of Japanese Spirit and Zen,The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 48, No. 3, December 2, 2013.

Related articles:

• Brian Daizen Victoria, Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. Suzuki

• Vladimir Tikhonov, South Korea’s Christian Military Chaplaincy in the Korean War – religion as ideology?

• Brian Victoria, Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima

• Brian Victoria, Karma, War and Inequality in Twentieth Century Japan

Sources

Campbell, Colin. “The Cult, the Cultic Milieu and Secularisation.” A Sociological Yearbook of Religion in Great Britain 5 (1972), pp. 119-136.

Cancik, Hubert (ed.). Antisemitismus, Paganismus, völkische Religion. München: Saur, 2004.

Deeg, Max. „Aryan National Religion(s) and the Criticism of Ascetism and Quietism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries“ in: Freiberger, Oliver (ed.): Ascetism and its Critics. Historical Accounts and Comparative Perspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, 61-87.

Deutsches Nonnenleben. Das Leben der Schwestern zu Töss und der Nonne von Engeltal. Büchlein von der Gnaden Überlast. Eingel. und übertr. von Margarete Weinhandl, Munich: O. C. Recht Verlag, 1921.

Dürckheim-Montmartin, Karlfried Graf von. “Gemeinschaft“ in: Klemm, Otto, Volkelt, Hans, Dürckheim-Montmartin, Karlfried Graf von (ed.): Ganzheit und Struktur. Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstage Felix Kruegers. Erstes Heft: Wege zur Ganzheitspsychologie, München: Beck Verlag, 1934, pp. 195-214.

_____. “Shujo-Dan.” Berlin – Rom – Tokyo. Heft 3, Jg. 1 (1939), pp. 22-28.

_____. “Tradition und Gegenwart in Japan.” Das XX. Jahrhundert. Juli 1939, pp. 196-204.

_____. “Japans Kampf um Japan.” Berlin – Rom – Tokyo Heft 6, Jg. 1 (1939), pp. 26-38.

_____. “Das Geheimnis der japanischen Kraft.” Zeitschrift für deutsche Kulturphilosophie. N.F. 6,1 (Tübingen 1940), pp. 69-79.

_____. “Zweck und Wert im Sinngefüge des Handelns.” Blätter für Deutsche Philosophie. Vol. 8 (1934/35), pp. 217-234.

_____. Neues Deutschland. Deutscher Geist – eine Sammlung von Aufsätzen. Zweite, verbess. Aufl. Tokyo: Sanshusha, 1942.

_____. “’Europe’?” The XXth Century, Shanghai, Vol. III (1942), No. 18, pp.121-134.

Dürckheim, Karlfried Graf von. The Japanese Cult of Tranquility. London: Rider & Company,1960.

_____. Wunderbare Katze und andere Zen-Texte. 2. Aufl. Weilheim: O. W. Barth Verlag, 1970.

_____. Erlebnis und Wandlung. Grundfragen der Selbstfindung. Erw. und überar. Neuausgabe Bern / München: Otto Wilhelm Barth Verlag, 1978.

_____. Mein Weg zur Mitte. Gespräche mit Alphonse Goettmann. Freiburg/Br.: Herder Verlag, 1985.

_____. Der Weg ist das Ziel. Gespräch mit Karl Schnelting in der Reihe “Zeugen des Jahrhunderts”. Hg. von Ingo Herrmann. Göttingen: Lamuv, 1992.

Eckprecht, Karl (pseud. of Karlfried Graf Dürckheim). Vom rechten Mann. Ein Trutzwort für die schwere Zeit. Berlin: Herbert Stubenrauch Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1940.

Gailus, Manfred / Nolzen, Armin, (ed.). Zerstrittene ‚Volksgemeinschaft’. Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011.

Gerstner, Alexandra: Neuer Adel. Aristokratische Elitekonzeptionen zwischen Jahrhundertwende und Nationalsozialismus. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2008.

Geuter, Wilfried: “The Whole and the Community: Scientific and Political Reasoning in the Holistic Psychology of Felix Krueger“ in Renneberg, Manika and Walker, Mark (ed.), Science, Technology and National Socialism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 197-223.

Goodrick-Clarke. The Occult Roots of Nazism. Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology: The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany, 1890-1935. Wellingborough: The Aquarian Press, 1985.

Grasmück, Oliver. Geschichte und Aktualität der Daoismusrezeption im deutschsprachigen Raum. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2004.

Hansen, H. T. (pseud. of Hans Thomas Hakl). “Julius Evola und Karlfried Graf Dürckheim” in: Evola, Julius: Über das Initiatische. Aufsatzsammlung. Sinzheim: H. Frietsch Verlag, 1998, pp. 51-70.

Harrington, Anne. Reenchanted Science. Holism in German Culture from Wilhelm II to Hitler, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Herrigel, Eugen. “Die ritterliche Kunst des Bogenschiessens.” Nippon. Zeitschrift für Japanologie 2:4 (1936), pp. 193-212.

Hippius, Maria. “Am Faden von Zeit und Ewigkeit. Zur Lebensgeschichte von Graf Karlfried Dürckheim” in Hippius, Maria (ed.), Transzendenz als Erfahrung. Festschrift zum 70. Geburtstag von Graf Dürckheim. Weilheim/Obb.: Barth-Verlag. 1966, pp. 7-40.

Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Zwei Bände in einem Band. Ungek. 855 Aufl. München: Franz Eher Nachf. 1943.

Ignatius von Loyola. Die geistlichen Übungen. Eingel. und übertr. von Dr. Ferdinand Weinhandl, München: O.C. Recht, 1921.

Jinnō-Shōtō-Ki. Buch von der wahren Gott-Kaiser-Herrschaftslinie verfasst von Kitabatake Chickafusa, übers. eingel. und erl. von Dr. Hermann Bohner. Erster Band. Tokyo. Jap.-deutsches Kulturinstitut 1935.

Junginger, Horst. „Deutsche Glaubensbewegung“ in Gailus, Manfred / Nolzen, Armin, (ed.). Zerstrittene ‚Volksgemeinschaft’. Loc. cit. 180-203.

Junginger, Horst: “Die Deutsche Glaubensbewegung als ideologisches Zentrum der völkisch-religiösen Bewegung” in: Puschner, Uwe / Vollnhals, Clemens (ed.): Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus. Eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte. Göttingen 2012, 65-103.

Kimura, Naoji. Der ostwestliche Goethe. Deutsche Sprachkultur in Japan. Bern 2006.

Moeller van den Bruck, Arthur: Das Dritte Reich. Berlin: Ring Verlag, 1923.

Muller, Jeremy Z.: The Other God That Failed: Hans Freyer and the Deradicalisation of German Conservativism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Poewe, Karla: New Religions and the Nazis. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Puschner, Uwe. Die völkische Bewegung im wilhelminischen Kaiserreich: Sprache – Rasse – Religion. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 2001.

Puschner, Uwe / Vollnhals, Clemens, (ed.). Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus. Eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012.

_____. “Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus. Forschungs- und problemgeschichtliche Perspektiven” in Puschner, Uwe / Vollnhals, Clemens, (ed.). Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus. Eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012, pp. 13-29.

Rollett, Brigitte. “Ferdinand Weinhandl. Leben und Werk” in Binder, Thomas et. al. (ed.). Bausteine zu einer Geschichte der Philosophie an der Unversität Graz. Amsterdam / New York: Rodopi, 2001, pp. 411-436.

Scherer, Eckart. “Organische Weltanschauung und Ganzheitspsychologie” in Graumann, Carl Friedrich (ed.): Psychologie im Nationalsozialismus. Berlin et al.: Springer-Verlag 1985, pp. 15-53.

Schnurbein, Stefanie von (ed.). Völkische Religion und Krisen der Moderne. Entwürfe „arteigener“ Glaubenssysteme seit der Jahrhundertwende. Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann, 2001.

Sedgwick, Mark. Against the Modern World. Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford 2004.

Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro: Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. Kyoto: Eastern Buddhist Society, 1938.

Tilitzki, Christian. Die deutsche Universitätsphilosophie in der Weimarer Republik und im Dritten Reich, Teil 1 und 2, Berlin: Akademieverlag, 2002.

Ular, Alexander. Die Bahn und der rechte Weg [1903]. Leipzig: Insel Verlag, 1917.

Wachutka, Michael. “‘A Living Past as the Nations´s Personality’: Jinnō shōtōki, Early Showa Nationalism, and Das Dritte Reich.” Japan Review 24 (2012), pp. 127-150.

Wehr, Gerhard. Karlfried Graf Dürckheim. Leben im Zeichen der Wandlung. Aktual. und gek. Neuauflage Freiburg/Br: Herder Verlag, 1996.