Japan’s Public Finance and the Dogmas of Neo-Liberalism

Jinno Naohiko

Translation by Ben Middleton

Translator’s Introduction: The Politics of Tax Reform in Japan

If the only certainties in life are death and taxes, in recent years struggles over tax policy and tax reform in

At the heart of the struggle is the bleak situation of

OECD Chart on General Government Gross Financial Liabilities in the OECD area

The situation will be exacerbated in the future by the projected decline in income tax revenues as the rapidly aging workforce moves into retirement. Moreover, in the 2004 pension system reform, the government committed itself to increasing its subsidy of the basic national pension from the current one-third to one-half by 2009, at the cost of an additional 2.3 trillion yen. All of this places a question mark over the sustainability of the present regime of public finances (Ministry of Finance, Current Japanese Fiscal Conditions and Issues to be Considered 2007).

There is wide recognition of the necessity to reconstruct public finances while simultaneously enhancing international economic competitiveness and maintaining social cohesion. However, consensus on how to achieve these goals remains elusive.

On the government side of politics, a neo-liberal taxation policy agenda has gained sway, notably during Koizumi Jun’ichiro’s term as prime minister from 2001 to 2006. In January 2002, the Koizumi government announced in its Structural Reform and Medium-Term Economic and Fiscal Perspectives (English summary available here) that it would return the budget to surplus by the early 2010s as a result of spending cuts achieved through micro-economic structural reforms, and increased tax revenues from a more competitive economy. This reflects two neo-liberal priorities: reducing the size of government and bringing the budget into balance. Koizumi’s successors’ efforts to realize this agenda have been constrained by the victory of the Democratic Party of

In the face of a difficult parliamentary situation, the current prime minister, Fukuda Yasuo, remains committed to a version of the neo-liberal agenda. He has spoken out in favor of increasing the consumption tax to 10% (currently it is 5%) and increasing reliance on indirect taxation. To the government, the merit of the consumption tax is that it provides a broad-based, stable source of revenue that, unlike income and company taxes, is not significantly affected by fluctuations in the level and rate of employment and business conditions.

It will, however, prove difficult to shore up public support for a straight increase in the consumption tax. Although the Japanese consumption tax rate is much lower than that in most OECD countries, it is more regressive because it is theoretically ‘pure,’ with no exemptions for food or other daily necessities. Therefore, any increase to double digits that does not make allowance for the impact on low-income earners—either through an exemption mechanism for food etc. or compensation through broader tax reform such as income tax reductions—will be politically unpalatable. These difficult issues are currently being debated in policy circles. For example, in a recent speech, Tanigaki Sadakazu, head of the powerful LDP Policy Research Council, has suggested that the government could increase the steepness of the (progressive) income tax-rate curve in order to offset the regressive effects of the consumption tax hike.

The most recent government policy statement concerning the consumption tax is the economic and fiscal policy white paper for fiscal 2008, submitted to cabinet on 22 July by Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Hiroko Ota (Report of the Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister: The Japanese Economy Confronting Risks, 2008 [in Japanese only]). It presents a case for lifting the consumption tax to finance social welfare programs whilst maintaining economic growth in an era when

The white paper anticipates that increased consumption tax revenues will cover the projected decline in income tax receipts as the population ages. It notes that whilst the consumption tax is regressive for income earners, it spreads its burden across generations because it places a burden on income earners and non-earners alike. The introduction of regional consumption taxes could also have positive effects on regional fiscal equality, as workers continue to drift away from the countryside to major cities, reducing income-based resident tax revenues. However, the paper also calls for discussion of ways the increased burden on pensioners and low-income earners can be mitigated by exempting or reducing the tax rate on food and certain other goods, and increasing the basic income tax deduction.

What is certain is that this is ultimately a political problem that will take time to resolve. The current economic slowdown in the wake of the global credit crisis and oil-shock, a possible cabinet reshuffle in the next few weeks, and an election that must be called by September 2009 decrease the likelihood that policy consensus will emerge anytime soon. Implementation of politically sensitive tax reform is therefore unlikely to occur in the next 2-3 years. Recently the mood for postponing the tax hike has spread, with former LDP chief cabinet secretary Yosano Kaoru stating that it was unrealistic to expect that the consumption tax could be raised next year (Mainichi Shimbun Online, 18 July 2008). Yosano, who had been an advocate of a swift hike in the tax, now argues that the financial uncertainty produced by the current global crisis, as well as electoral considerations, mean that the hike should be postponed for another ten years.

In the meantime, with opinion polls underlining the fragility of the Fukuda administration, the government continues to press for tax reform. Chief Cabinet Secretary Machimura Nobutaka announced on July 1 that the LDP will hold a ‘drastic debate on tax reform.’ The LDP Research Commission on the Tax System is scheduled to compile its tax reform outline for fiscal 2009 by December (The Guardian, ‘Japan LDP kicks off tax debate including sales tax,’ July 1 2008). The head of the Commission,

As the Fukuda government contemplates its next move, the memory of the poisonous effect that the consumption tax has had on the electoral fortunes of previous governments will surely weigh heavily. The first casualty was the Ashida government, which tried to implement a broad-based sales tax in 1948, only to scrap it in the face of antipathy from the public, business interests and the Shoup Commission. This still did not prevent it from losing the election the following year. The Ohira government was the next casualty, suffering defeat in the 1979 election after floating the idea of a ‘general consumption tax’ in 1978. (Incidentally, Ohira’s arch rival at the time was the father of the current prime minister.) It would take another ten years before the idea was taken up again, this time by the Nakasone government. Nakasone had set his sights on introducing a ‘sales tax’ as part of a ‘fundamental reform of the taxation system.’ However, loss of the 1987 nationwide local government elections forced him to abandon the plan.

In late 1988, the Takeshita cabinet pushed through legislation for a consumption tax to come into effect in April 1989 (the start of the Japanese fiscal year) at a rate of 3%. Unsurprisingly, the LDP suffered a heavy defeat in the House of Councillors elections later that year. Of course, the Recruit bribery scandal that became public at this time did little to help Takeshita’s prospects. In 1994, the Hosokawa cabinet proposed increasing the consumption tax rate from 3% to 7% to create a consumption tax-based ‘national welfare tax.’ Negative public reaction quickly forced Hosokawa to abandon the idea. Then in 1997, the Hashimoto cabinet increased the consumption tax to 5%, only to incur defeat in the 1998 upper house election. Hashimoto stepped down as prime minister to take responsibility.

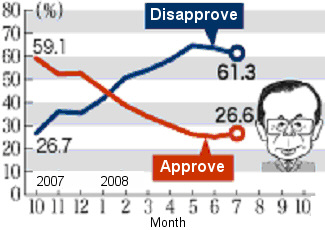

Overcoming the legacy of the past will require incredible political will. The question remains, can the LDP-Komeito coalition find this will or policies that win public approval? This may prove a hard task, as public approval of the Fukuda cabinet has plummeted from the near 60% it enjoyed in October 2007 to 22% in the latest Mainichi Shimbun newspaper telephone poll, and 26.6% in the latest Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper face-to-face poll. Fukuda’s personal approval rating is also in the ‘danger zone’ below 30%. Not only is there a striking lack of consensus on specific policy measures within the ruling coalition, but unless the ratings pick up, Fukuda may be forced to resign, as frustration grows within the LDP that winning an election under his leadership would be impossible.Such an upheaval would only delay policy formation within the coalition.

Public Support for the Fukuda Cabinet

Source: Yomiuri Shimbun

In this essay, Jinno Naohiko, a professor of public administration in the

Despite their differences, all three policy lines attempt to move toward what Jinno calls a new ‘common sense’ with regard to tax policy and public finance. This is nothing other than the ‘public recognition’ that LDP Tax Commission chief

Formation of this ‘common sense’ is by no means complete. Although it gained ground as the ‘Koizumi theatre’ helped the LDP romp home in the 2005 Lower House election, public sentiment shifted in the 2007 election towards criticism of growing social inequality. (See Yamaguchi Jiro and Miyamoto Taro, What Kind of Socioeconomic System Do the Japanese People Want? Increasing the consumption tax is supported by the Ministry of Finance, which has long been determined to secure a broader-based source of revenues in the face of changing economic and demographic structures, especially the rapid ageing of the workforce. It is also supported by

In the political sphere, opponents of the neo-liberal agenda within the LDP have been silenced but have not disappeared. The Democratic Party of

The Return of the Dogma of Balanced Budgets

There are two words in the Swedish language that I like. One is ‘lagom,’ while the other is ‘omsorg.’ Both words have deep roots in the particular system of values developed by the Swedish people over the course of their long history.

Lagom means ‘in moderation,’ or ‘not overdoing things.’ For the Swedish people, who dislike extremes of wealth and poverty, it connotes the virtue of the golden mean. This implies as well the importance of finding a balance not only between the rich and poor strata of society, but also between the plentiful and impoverished areas of life.

Omsorg means social services. The sense of the Swedish word is much broader than the Japanese shakai fukushi, which is usually translated into English as social welfare, because it describes in general all those public services that underwrite the living conditions of the population. However, the original meaning of omsorg was ‘sharing sorrows’ or ‘caring for one another.’ In other words, in

Lagom and omsorg can be seen as two concepts that hold the key to solving contemporary

In public finance, which is administered by cooperative decision-making among the constituents of society, common sense plays an important role. Of course, common sense and reality often diverge. Or rather, policy differences concerning public finance administration often involve struggles over the formation of common sense with regard to public finance.

According to the economic journalist Okonogi Kiyoshi, opposing policy lines concerning public finance administration in

For all that, although these three policy lines stand opposed to each other, they share the same common sense—the dogma of fiscal balance that asserts that it is healthy for fiscal policy to keep revenues and expenditure in equilibrium, and that overseeing this is the objective of fiscal administration. That is to say, from the perspective of this dogma of balanced budgets, in order to balance the budget, there is no alternative to raising taxes, or if taxes are not raised, the only options are to rely on a natural increase in tax receipts, or to cut spending.

However, common sense is not necessarily truth. The dogma of balanced budgets may certainly have been common sense since the heyday of Adam Smith, founder of the school of classical economics. Yet this common sense came to be discredited by John Maynard Keynes.

According to Takahashi Masayuki, a lecturer at

Of course, the question of ‘shifting the burden to future generations’ is still being theoretically debated, and no conclusion has yet been reached. In the 2000s, in addition to arguments against ‘burden shifting,’ ‘concerns about future tax increases’ and ‘concerns about future fiscal collapse’ have also been aired. The ‘Recommendations Concerning the Drafting of the 2008 Budget’ released on 19 November 2007 by the Ministry of Finance’s Fiscal System Deliberative Council, pointed to concerns about ‘postponing the burden to future generations’ as well as ‘raising interest rates.’ (The report is available in Japanese here.)

Mobilization of this kind of many-faceted theory has once more led to the dogma of balanced budgets being exalted as common sense. John Kenneth Galbraith may have had a point when he suggested that, ‘No society ever seems to have succumbed to boredom. Man has developed an obvious capacity for surviving the pompous reiteration of the commonplace.’

The Dogma of ‘Small Government’

Even more than truth, common sense is formed by the victors of an era. Or rather, it is the privilege of the victors to mobilize the media over and over again and propagandize until common sense is formed.

It is best to approach common sense with a good dose of suspicion. Why? Because behind common sense there often lurks the policy claims of the victors. We must not forget that the dogma of ‘small government’ often lies behind the dogma of balanced budgets.

The dogma of ‘small government’ is that economic growth will occur if only the size of the government sector is reduced. The ‘rising-tide policy line’ of the ‘natural increase faction’, which argues that fiscal rehabilitation will be achieved as a result of a natural increase in tax revenues, is based on this dogma. At first glance, the ‘administrative reform policy line’ propounded by the razor gang faction clamoring for expenditure cuts and the ‘desperately staving-off-bankruptcy line’ put forward by the ‘raised-taxes-are-inevitable faction’, appear to stand opposed. Yet in so far as they are both based on the dogma of ‘small government,’ there is no difference between them.

The ‘raised-taxes-are-inevitable faction,’ which thinks

Furthermore, the ‘desperately-facing-bankruptcy theory’ propounded by the faction that sees raising taxes as inevitable restricts itself to talking about the consumption tax. In other words, when it argues that ‘in order to stop runaway budget deficits, tax increases are inevitable,’ it isn’t talking about raising company or individual income tax rates. It simply screams out obsessively for an increase in the consumption tax.

Or rather, although policy lines diverge on the question of whether taxes should be raised or not, the only tax that is subject to discussion is the consumption tax. This is because of a common faith in the dogma of ‘small government.’

Normalization of the Three Dogmas

The dogma of ‘small government’ can also be regarded as a dogma of ‘necessary evil.’ This dogma asserts that the market will not function if property rights are not coercively established and enforced. The existence of a government with coercive powers is necessary to achieve this outcome; yet it is a necessary evil in that it constrains economic growth.

The dogma of ‘small government’ and the dogma of ‘balanced budgets’ is the common sense that neo-liberalism has tried to create in order to negate fundamentally the welfare state that had become ubiquitous in post-World War II advanced capitalist societies. We can now say that this attempt was hugely successful.

The reason why these dogmas of neo-liberalism—‘small government’ and ‘balanced budgets’—were successfully normalized as common sense was that they stimulated a nostalgia for the ‘golden thirty years’ of high-speed economic growth that was achieved after World War II. The post-WWII ‘Keynesian welfare state’ that rejected both ‘small government’ and ‘balanced budgets’ balanced economic growth and income redistribution and so achieved the ‘happy marriage between economic growth and income redistribution’ that we call the ‘golden thirty years.’ However, high-speed growth took a body-blow from the stagflation brought on by the oil shocks.

Neo-liberalism challenged the common sense of the Keynesian welfare state and tried to put in its place the common sense that what made economic growth possible was ‘balanced budgets’ and ‘small government.’ It linked ‘balanced budgets’ and ‘small government’ together in the context of economic growth. Under neo-liberalism, even if it becomes necessary to raise taxes to ‘balance’ the budget, this must not be linked to increasing the provision of the social services that support the daily lives of the people. It is necessary to ensure that the future tax burden does not expand, thus becoming an impediment to economic growth.

However, neo-liberalism also asserts that tax increases per se must not be allowed to become a drag on economic growth. In order to achieve this, it proposes shifting the taxation burden from high-income to low-income earners. The watchwords of taxation reform are thus ‘a move to a broad-based but light tax burden,’ and ‘from an income tax to a consumption tax.’

Under the Keynesian welfare state, the prevailing common sense suggested implementing a redistributive taxation system centered on high individual income and company taxes. Such a taxation system based on individual income and company taxes with high income elasticity had a strong economic stabilizing function, and also ensured the provision of public services through its superb resource distribution function. That is, under the Keynesian welfare state, a consensus emerged holding that it was desirable, from the point of view of resource distribution, income redistribution and economic stabilization—the three functions of public finance—to create a tax system based on income tax and company tax.

Neo-liberalism turned this common sense upside down, placing it against the backdrop of stagflation and economic stagnation. Neo-liberalism argued instead that what was desirable was a neutral tax system that did not redistribute income distributed by the market, and advocated what in

The dogma of ‘necessary evil’ with regard to fiscal disbursements, the dogma of ‘economic neutrality’ with regard to tax revenues, and the dogma of ‘balanced budgets’ with regard to treasury budgets was the common sense of the era of laissez faire economics in the mid-nineteenth century. However, we must not forget that while governance functions during the era of laissez faire were restricted to security functions based on coercive forces such as the military and the police, a great range of functions were fulfilled by the informal and volunteer sectors—composed of families, communities, churches etc.—which had acquired expanded scope.

While it is often remarked that even those who lost out to the principle of competition in the market economy were able to survive the laissez faire era of the mid-19th century through self-help, this was not individual self-help. It was a type of self-help predicated on an expanded network of communal relations within and through families and communities.

Furthermore, the sphere of the market economy was small, and daily life was not heavily dependent on the market. It was for that reason that consumption taxes and taxes on luxury and profligacy were admitted. Thomas Mann, for example, supposed that a consumption tax would impose little burden on the poor yet would be a burden on the rich.

However, the forms of daily life of low income earners today are highly dependent on the market economy. Or rather, the safety-net functions formerly provided by the family and community have shrunk, while the volume of goods and services bought in the market has increased spectacularly. It is in this situation that neo-liberalism is attempting to normalize the three dogmas by one-dimensionally expanding the ‘sphere of the market’ based on the principle of competition.

Reality as the Enemy of Common Sense

The most powerful enemies of common sense are reality and truth. A common sense contradicted by reality and truth cannot be accepted by the public over the long term.

According to the annual Cabinet Affairs Office Public Opinion Survey of Social Consciousness, over the past three years Japanese social consciousness has changed dramatically. Figure 1 shows the composition of the rank order of responses to a question about the areas of life people think are ‘heading in the right direction.’ The top six responses from 1998 to 2005 were stable. However, from 2005, a dramatic change in the rank order can be observed.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Two main factors caused this dramatic change. First, the number of people who selected ‘health care and welfare’ as areas they felt were ‘heading in the right direction’ dramatically declined. The numbers fell from 27.2% in 2005, to 23.1% in 2006, to 16.5% in 2007.

The second factor is the change in responses to a question about ‘the economy.’ Despite a record of economic growth ‘exceeding the Izanagi boom’ [the 57 months of continuous growth from October 1965 to July 1970—trans.], of all areas of daily life ‘heading in the right direction,’ ‘the economy’ was stuck at number six (that is, lagging behind five other areas of life. Tr) until 2005. However, the percentage of those who felt that economic conditions were good increased from 5.3% in 2005 to 16.9% in 2006, before declining markedly to 12.3% in 2007.

Turning to Figure 2, which describes ‘areas of daily life moving in a bad direction,’ there is a big change between the situation before and after 2005. Until 2005, the proportion indicating that ‘public safety’ ‘was heading in a bad direction’ was increasing rapidly, reaching the top position in 2005 with 45.3% of responses.

However, after 2005 the proportion of respondents who thought ‘education,’ ‘healthcare and welfare,’ and ‘regional disparities’ were ‘heading in a bad direction’ increased rapidly. ‘Education’ marked 28.6% in 2005, and although declining to 23.8% in 2006, sprung up to 36.1% in 2007 to take the top spot. ‘Healthcare and welfare’ rose rapidly from 15.2% in 2005 to 31.9% in 2007. Regional disparities also increased markedly in responses from 9.7% in 2005 to 26.5% in 2007.

Looking at the Cabinet Office public opinion survey results, one cannot conclude that the public thinks the economy is heading in the right direction, nor that employment and working conditions have improved as a result of the structural reforms imposed under the banner of ‘small government.’ Even looking at the responses to the question about ‘areas of daily life heading in a bad direction,’ ‘employment and working conditions’ is hovering at a high level. Further, the public has concluded that public services such as ‘healthcare and welfare,’ ‘education’ and so on have rapidly deteriorated as a result of structural reform.

However, the deterioration of public services has exacerbated the problem of social inequality (kakusa mondai). In the 1990s,

However, if we examine disposable income after initial income has been redistributed by fiscal policy, even though Japan was equitable in comparison with the US and the UK, it was less equitable compared with European countries. The income redistribution function of

However, as Prof. Miyamoto Taro of the Graduate School of Public Policy at

The weight of social assistance expenditure (welfare) in the Scandinavian countries such as

Table 1: Social Expenditures, Gini Coefficients and Relative Poverty Rates of Various Countries (1992 GDP data)

|

|

Social Assistance Expenditure (%) |

Gini Coefficient |

Relative Poverty Rate (%) |

Social Expenditures (%) |

|

|

3.7 |

0.361 |

16.7 |

15.2 |

|

|

4.1 |

0.321 |

10.9 |

23.1 |

|

|

1.5 |

0.211 |

3.7 |

35.3 |

|

|

1.4 |

0.213 |

3.8 |

30.7 |

|

|

2.0 |

0.280 |

9.1 |

26.4 |

|

|

2.0 |

0.278 |

7.5 |

28.0 |

|

|

0.3 |

0.295 |

13.7 |

11.8 |

Sources: Social Expenditure data from the OECD Social Expenditure Database; Social Assistance Expenditure data from Tony Eardley et al, Social Assistance in OECD Countries: Synthesis Report, Department of Social Security Research Report No.46, p35; Gini coefficient and relative poverty rate data in mid 1990s from OECD, Society at a Glance: OECD Social Indicators.

The weight of social assistance expenditures in

The ‘paradox of redistribution’ that Korpi identified is the phenomenon whereby the higher a country’s social assistance expenditure, the higher are its level of income inequality and poverty rate.

There is no question that paying cash benefits just to the poor has an effect on ‘vertical redistribution.’ However, it has been supposed that social benefits to support people who have fallen into situations of risk, regardless of whether they are rich or poor, are only effective as a form of ‘horizontal redistribution.’ In fact, however, countries giving a greater weight to expenditures on social programs thought to only have a ‘horizontal distributive’ effect experience lower poverty and more equitable income distributions. This is the ‘paradox of redistribution.’

Turning to the Japanese case, the weight of ‘horizontally redistributive’ social benefits expenditure is low. But this is not to say, as the ‘paradox of redistribution’ would suggest, that poverty is low and income distribution is equal. Both the Gini coefficient and the relative poverty rate are high. The most we can say is that the numbers for both social assistance and social expenditure are lower than those of the

Despite the low weight of ‘vertically redistributive’ social welfare expenditures in Japan, the reason why poverty is not insignificant and income distribution is not equitable as the ‘paradox of redistribution’ suggests it should be, is that the weight of ‘horizontally redistributive’ social welfare expenditure is also low, indeed, lower than all of the other countries in the table. Despite poverty being significant and society being unequal, it is primarily due to this fact that Japanese society cannot be called unequal or plagued by poverty when compared against the Anglo-Saxon societies of the US and UK, that Japan gained its reputation as ‘oppressively egalitarian.’

The

The structural change in social consciousness after 2005 revealed by the Cabinet Office Public Opinion Surveys of Social Consciousness suggests that the common sense propagandized by the ‘small government’ of neo-liberalism is starting to crumble. A common sense that ignores reality cannot be supported by the public over the long term.

What the public demands is not ‘small government,’ but public services such as education, healthcare and welfare, and overcoming the imbalances caused by the swollen market economy. That is, the public want a reasonable balance, a lagom between the public sector and the private sector.

The ‘paradox of redistribution’ shows us that a lagom that can recuperate such imbalances in public services will tend to equalize income inequalities and also alleviate the poverty rate. That is, a lagom between the public and private sectors will be tied to a lagom that provides a reasonable balance of income distribution.

Of course, such a lagom or ‘reasonable’ government will be able to realize a sphere of ‘sharing the sorrows’ based on the communal decision-making of all members of society. However, in order to realize a reasonable omsorg based on the decision-making of the members of society, a public sphere that is readily accessible must be created that enables communal decision-making. That is, in order to empower society’s members with the authority to decide the future of society and daily life, it is necessary to devolve power from the central government to local and regional authorities. Horizontal redistribution through the provision of services such as welfare, healthcare, and education should be achieved by local governments providing services in accordance with the needs of local societies.

However,

Despite this, the common sense that the only option for raising taxes is the consumption tax is pushing ahead with impunity. Or rather, precisely because of this, a big campaign has started proclaiming that the only possible tax that can be raised is the consumption tax.

Moreover, its proponents are falling over themselves trying to create the common sense that the consumption tax is not regressive. They stress that while the consumption tax is regressive with respect to income, it is proportional with respect to consumption. What is more, because income is invariably consumed, over the whole life-span of a person, lifetime income and lifetime consumption should be equal. They triumphantly conclude that the burden of the consumption tax is not regressive because it is levied proportionally against lifetime income.

In order to argue that income is invariably consumed, it is necessary to view inheritances as consumption. However, human beings are not born as adults. If one regards inheritances as consumption, then even should income be invariably consumed, human life begins not with income but with consumption. That is, people are supported by their parents until they become adults, and only start earning an income after a long period of consumption. Although income is invariably consumed, consumption is not invariably consumption of earned income. If we take into account the period of consumption before people become adults, lifetime consumption does not equal lifetime income.

Because public finance in

Figure 5

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook, Dec. 2006, Issue 80, Statistical Annex.

We would rather say that the fiscal crisis was all along nothing more than the result of a social and economic crisis. A deepening of the economic crisis will invariably produce a fiscal crisis. Fiscal crises also invariably follow social crises such as war. There is no point whatsoever in exacerbating an economic crisis and a social crisis in order to resolve a fiscal crisis.

The common sense that needlessly fans fiscal crisis operates under the assumption of redeeming the entire stock of outstanding government bonds. Yet from the perspective of historical reality, this assumption is not valid. This is clear when we remember, for example, that bonds issued by the British government in the 19th century [during the Napoleonic wars—trans.] were perpetual debt obligations that were never redeemed.

The mission of public finance is to resolve economic and social crises, and to realize ‘happiness in society’ or eudaemonia. What the public fears is that the welfare, healthcare, education and other such public services necessary to achieve eudaemonia are being discarded.

Should we fall under the Midas spell that seduces us with the idea that we can achieve happiness if everything we touch turns to gold, all solicitude for others and the ‘sharing of sorrows’ will be lost. Such a society will never be a eudaemonia. The mission of public finance must not only be to deal with ‘market failures.’ It must also be the lagom that restores the imbalances that arise between the public and private sectors, between work and life, as well as the nurturing of a life community that can ‘share its sorrows.’

This article appeared in the April 2008 issue of the current affairs journal, Sekai (The World). Jinno Naohiko is professor of public finance in the

Translation and introduction for Japan Focus by Ben Middleton, Associate Professor of Sociology, Ferris University, Yokohama, and currently visiting Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia. His recent publications include: ‘Scandals of Imperialism: The Discourse on Boxer War Loot in the Japanese Public Sphere’ in Robert Bickers & Gary Tiedemann (eds.) 1900: The Boxers,

Posted at