Russian Energy Maneuvers Challenge

By Hisane Masaki

In September, the Russian Natural Resources Ministry froze a key environmental permit for the project off the Coast of Sakhalin Island, citing problems with conservation. The decision drew immediate protests from

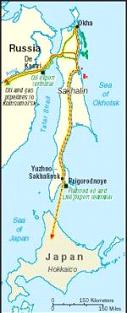

Map of

gas projects and pipelines

The project is operated by an international consortium called Sakhalin Energy, in which Royal Dutch Shell has a 55% stake. Japanese trading firms Mitsui and Mitsubishi hold 25% and 20% shares, respectively.

Natural gas taken from two fields off the northeast coast of the island will be transported through an 800-kilometer pipeline to Prigorodnoye, in the island’s southernmost part, where it will be liquefied and shipped to

To be sure, even before

With prices for crude oil and other natural resources at high levels, the Russian administration of President Vladimir Putin has been promoting a strategy to place energy under national control. The major oil company Yukos, which was hostile to the government, was charged with tax evasion and eventually forced to dissolve.

Sakhalin-2 is the only wholly foreign-funded project among major resource development programs in

Putin acknowledged on Friday that the conditions of the contract, known as a production-sharing agreement, and increasing costs for Sakhalin-2 are disadvantageous for his country because

In what appears to be the latest in a series of Russian efforts to take greater control of domestic energy resources, Gazprom said this month that it will develop the giant Shtokman natural-gas field in the

Optimism on both sides

In what was seen by some as a conciliatory tone, however, Russian Natural Resources Minister Yuri Trutnev gave Sakhalin-2’s operator a month – until the end of October – to come up with plans to rectify what they called major environmental violations before a possible shutdown of the $20 billion operation. The plans are to be submitted to the minister in the final week in October.

Royal Dutch Shell’s chief executive said that the company has fully addressed all ecological issues and is seeking dialogue with the Russian authorities. “Although the project has faced significant environmental challenges, we firmly believe these have been fully and transparently addressed,” Jeroen van der Veer told an investment advisory council chaired by Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov.

“This project is 80% complete now with all LNG [liquefied natural gas] pre-sold under long-term contracts … We are confident that all remaining issues can be resolved through our ongoing, constructive and fair dialogue with the Russian government.”

Trutnev said that if the company’s plan is acceptable, the development won’t be stopped, and noted that he had received assurances from the Royal Dutch Shell head that the energy giant is working to resolve the problems. Trutnev praised the company for taking a constructive approach to

“My meeting … with van der Veer represents a 180-degree about-turn,” Trutnev said. “He talked about existing violations, about ecological standards and how they have already started improving the situation.” Trutnev noted, however, that “absolutely any sanctions” are possible if the proposals prove unsatisfactory. Trutnev’s ministry will announce the results of its environmental probe into Sakhalin-2 as early as this week.

Japanese Minister for Economy, Trade and Industry Amari Akira also expressed optimism recently about the fate of Sakhalin-2. Amari said he thought there would be a resolution between the Sakhalin Energy and the Russian government over the recent problems. “One way or another, Sakhalin-2 will be resolved,” Amari said. “The basic contract hasn’t been nullified.” Amari said he thought Sakhalin Energy would be able to convince

The Sakhalin-2 project is expected to provide 9.6 million tons of LNG a year from 2008. Eight Japanese companies, including Tokyo Electric Power Co, Tokyo Gas Co and Chubu Electric Power Co, have agreed to purchase 4.73 million tons per year – equivalent to 8% of

Molikpaq offshore platform currently used for producing oil at Sakhalin-2

If imports from Sakhalin-2 are delayed for an extended period, affected Japanese companies would need to find alternative suppliers. It remains to be seen, however, whether

The

Headwinds against

The

But this 40% target for “Hinomaru oil” has become even more difficult to achieve following

After hectic haggling,

Meanwhile,

Last year

The banner reads, “I am not a guest here. I am the returning

son. Here, for me everything is both beloved, and holy.”

In yet another blow to

The Sakhalin-1 development started on the condition that all of the 6 million tons of natural gas for export purposes – the amount excluding that to be taken by

Meanwhile,

Russian state pipeline monopoly Transneft is building the pipeline in two stages. It expects to finish the first stage at Skovorodino in 2008. Construction work on the first stage linking Taishet and Skovorodino began in late April. No date has been set for the second stage. There are strong expectations that imports of oil from eastern Siberia through the proposed pipeline to Russia’s Pacific coast, if and when they go into full swing, will help diversify oil sources and contribute to stable oil supplies to Japan in the long term.

Japan on the diplomatic defensive

Not long ago, it was thought that

The current situation is a stark contrast with just about a decade ago when Putin’s predecessor Boris Yeltsin made what the current Russian government now thinks were too many concessions on the territorial dispute, driven by the need to seek Japanese help in turning around the then ailing Russian economy.

While Japan’s economic power has been relatively on the decline after the burst of the asset-inflated “bubble economy” of the late 1980s, the Russian economy has been barreling ahead in recent years, thanks to high prices of crude oil, the country’s main export item.

These days, the attraction of the Russian economic magnet for

The two biggest Japanese auto makers,

Many analysts say, however, that if

There is growing international distrust of

In

On the oil pipeline linking eastern

Prime Minister Fradkov is expected to visit

Hisane Masaki is a Tokyo-based journalist, commentator and scholar on international politics and economy. Masaki’s e-mail address is [email protected].

This is a slightly edited version of an article that appeared in