Nihonga to Nihonga : Young, fresh and traditional Japanese artists

By C.B. Liddell

Some people complain that poetry has never been the same since poets were absolved of their obligations to rhyme and rhythm. The same people also think that since the 1968 scrapping of the Hollywood Production Code that regulated sexual content, movies have lost a lot of their sexual sizzle.

This belief — that creativity works best within certain constraints — also has its supporters in the art world.

Comparing a 19th-century French Academy masterpiece with globules of paint tossed onto a canvas by some 1950s New Yorker in his loft is perhaps too obvious an example; but the point is well made by “Annual 2006,” the yearly chance for the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOT) to change Tokyo’s artistic temperature by pouring in hot or cold, fresh young art.

Right now, the steam is climbing the tiles.

Usually these showcases for up-and-coming artists prove disappointing, displaying a derivative mishmash of art-college styles. But this year, with “From Nihonga to Nihonga,” the MOT curators have excelled, choosing contemporary artists working within the framework of nihonga, the self-consciously nationalistic style of art that arose at the turn of the 19th century as a reaction to the inroads being made by Western art.

“MOT annual exhibitions always have a theme,” exhibition curator Hiroko Kato explained. “For example, the theme of ‘Annual 2005’ was ‘gender,’ and the 2004 show’s was ‘identity.’ We decided to give it a Nihonga theme this time because we thought that the art works in this exhibition should serve as a new picture of Japan.”

Unlike the vague terms “gender” and “identity,” nihonga has a definite artistic meaning delimited by the form’s use of mineral pigments, linear drawing, decorative backdrops, lyrical expression and symbolism. Hence the current show has a much more consistent character, making it possible to easily judge the seven artists’ attempts to catch the contemporary Japanese spirit by improvising within these parameters.

“There is no meaning remaining in the old values of kacho fugetsu [flowers and birds, wind and moon],” artist Natsunosuke Mise said, regarding the artists’ rejection of traditional subject matter. Still, Mise’s own works — giant, rambling landscapes doodled in dye, Indian ink, metal powder, acrylic and whiting on gold-leaf paper — while presenting jumbled fragments of modernity, keep coming back to the unifying motif of Fuji-shaped mountains.

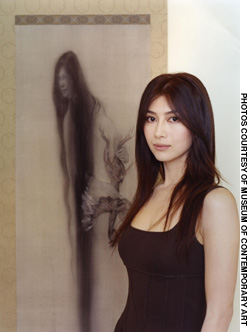

Other artists in the exhibition, such as Fuyuko Matsui, diverge more strongly from traditional subjects. With morbid themes and titles such as “A Blind Dog” (2005) and “Nyctalopia” (2005), Matsui introduces a dark Gothic sensibility that would have nihonga’s founders spinning in their graves. Although her subject matter is clearly beyond the pale of tradition, no artist in this exhibition does more to maintain techniques and textures — her disturbing images are skillfully executed on silk, then mounted on traditional patterned fabric.

In “Nyctalopia,” a ghostly long-haired woman does something very nasty to a chicken, while “Keeping Up the Pureness” (2004) shows a naked woman sliced open like a piece of fruit and lying amid beautifully painted flowers and plants that typically feature in more conventional nihonga. Such beautifully crafted images create a disturbing and mesmerizing effect that Matsui hopes will convey “a condition that maintains sanity while being close to madness.” Though such disturbing subject matter would normally seem puerile, it clearly gains here from its traditional execution.

The same could be said for the surprising and often hilarious images by Kumi Machida that evoke the geeky world of the otaku with a mixture of sexuality and artificiality. These works, which apparently explore odd associations that creep into the artist’s mind, gain artistic dignity from the beautiful kumohada linen paper that she uses, as well as her eloquent and flowing brush lines in blue-black Indian ink.

The innocent thrill of mixing nihonga with contemporary sensibilities is most apparent in Hisashi Tenmyouya’s 2001 ukiyo-e-style print in acrylic, “Contemporary Japanese Youth Culture Scroll — Para Para Dancing (Great Empire of Japan) vs. Break Dancing (America).” The scroll presents a face-off between Japanese hip-hop boys and para-para dancing girls. Once again the effect is humorous, prompting a suspicion that the attention given to such art may be short-lived.

Hisashi Tenmyouya’s work, described as

“like Wu-Tang, but from a Japanese

perspective,” portrays Asian hip hop culture.

But for anyone who’s peeked in karaoke boxes or passed mirrored public spaces where wannabe breakdancers bust their moves, these characters are just as in keeping with Japanese culture as any geisha giggling behind a long sleeve. And though this exhibition can be seen as a clash of generational cultures, what is happening is more complicated. As the insolence and iconoclasm of youth draws strength from tradition, it ultimately becomes part of that tradition.

“The rules of nihonga help young artists to focus their creative power,” Kato commented. “By acquiring the technique of nihonga, they are not biased toward the artistic tendency of Europe and America, so it helps them make unique art.”

Ultimately, in encouraging them to be both unique and Japanese in an artistic sense, the theme of “Annual 2006” has helped these young artists rebel against the real conservatism — that of being derivative.

C. B. Liddell is a Tokyo-based writer, editor and cartoonist. Originally published on The Japan Times on March 9, 2006. Posted on Japan Focus, April 5, 2006.